In historical literature there is often a statement that Joseph Stalin personally was behind the murder of the Leningrad party leader. We decided to find out if this is really so.

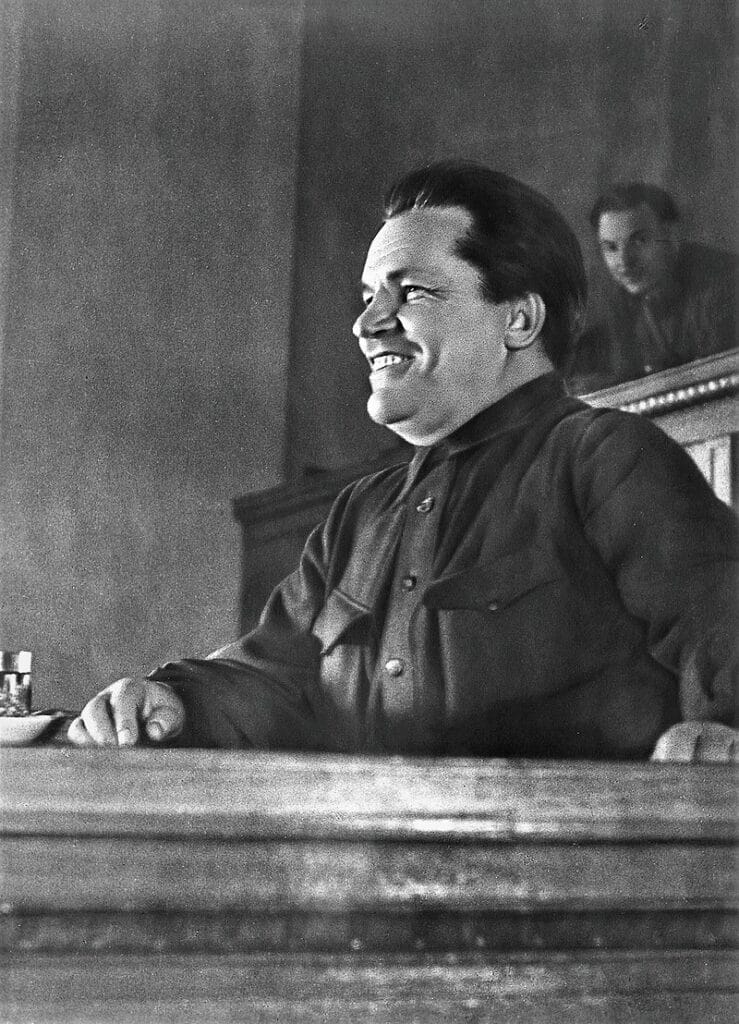

Sergei Kirov, head of the Leningrad party organization and member of the Politburo, was considered one of the most influential Soviet politicians in the early 1930s. On December 1, 1934, he was shot dead in Smolny, where the governing bodies of Leningrad were located, right next to his office.

Rumors that Joseph Stalin was behind the crime began to spread almost immediately after the murder. In Soviet folklore, for example, existed seditious ditty: “Oh, cucumbers and tomatoes, / Stalin killed Kirov in the corridor.” However, there is no evidence of its spread in the 1930s - researcher of the history of popular expressions Konstantin Dushenko attributed its appearance around 1961, that is, the time of the thaw and criticism of the Stalinist cult of personality.

Detailed hypothesis about the conspiracy led by Stalin outlined in his memoirs, former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. In addition, the version of Stalin as the orderer of Kirov’s murder was shared by some historians who wrote about the USSR in the 1930s, for example Roy Medvedev And Robert Conquest.

The murder of Kirov was committed by a former employee of the Leningrad regional committee, Leonid Nikolaev. By official version, presented in court at the end of December 1934, Nikolaev was a participant in a conspiracy that included party leaders opposed to Stalin and his policies. Nikolaev and 13 others were shot On December 29, the authorities placed moral and political responsibility for the murder on Zinoviev and Kamenev, former leaders of the party opposition to Stalin. Thus, the murder of Kirov became the reason for mass repressions and the tightening of Stalin’s control over the party apparatus.

By versions Khrushchev, which he presented at the 20th Party Congress, and then developed in his memoirs, Stalin was the organizer of the murder. He gives the following arguments in favor of this hypothesis:

- Kirov was a charismatic leader and was popular in the party, which theoretically could have threatened Stalin's position. Allegedly, at the XVII Congress (in January-February 1934), a number of party leaders tried to organize a conspiracy so that Kirov would replace Stalin as General Secretary. Kirov himself refused and told Stalin about the plans, and he decided to eliminate his competitor;

- The circumstances of the murder look very suspicious. Nikolaev was able to freely enter the well-guarded Smolny, carrying a firearm. Moreover, by that time he was on the police’s radar, since earlier, on October 15, he had already been detained with a weapon near Kirov’s house, but then released without charges. Oddities are also found in the actions of Kirov’s guards on the day of the murder, especially Borisov’s guard: when Kirov walked towards the office along the corridor, Borisov fell behind a little and did not have time to stop the killer. And the next day Borisov, official version, died in a car accident while being taken to Stalin for interrogation;

- Stalin directly and greatly benefited from Kirov's death: he began a large-scale purge of the party ranks, physically exterminating the remnants of the opposition.

The study of the circumstances of Kirov’s murder is complicated primarily by the large volume of sources. In addition to the documents of the initial investigation, these are also materials of special party commissions, who tried the case (there were six between 1956 and 1989). At the same time, not all of these documents have been published and introduced into scientific circulation, and a small part of them even remains unclassified. The most complete selection of materials available is presented in the collection “Echo of a shot in Smolny"

Researchers are unanimous in the opinion that the initial investigation was conducted with gross violations of even the law of that time. In addition, the investigation’s conclusions about Nikolaev’s connection with the Zinoviev opposition are not based on evidence, but were dictated personally by Stalin. However, the activities of later commissions, obviously, were not completely impartial, especially since their work was directly supervised by the highest party leadership.

There are a number of arguments against the version of Stalin’s involvement in organizing the murder of Kirov. The historian Oleg Khlevnyuk formulated them most fully - for example, in the book “Stalin. The life of one leader" He points out that there is no, even indirect, archival evidence of a conspiracy against Stalin at the 17th Party Congress. Kirov himself, although formally a member of the Politburo, rarely came to meetings of the highest party body in Moscow. According to Khlevnyuk, he “was and until the last moment remained a faithful supporter of Stalin, was never considered in the party as a political figure comparable to Stalin, and did not put forward any political programs different from Stalin’s.”

Moreover, how writes Khlevnyuk, in comparison with previous and subsequent repressions, the purges after the murder of Kirov were not so large-scale. “Contrary to popular belief, there was no extraordinary surge in terror after the murder of Kirov. Both in 1935 and 1936, despite the expulsion of many thousands of “suspicious” residents of Leningrad and the arrests of former oppositionists, repressions did not reach the level of cruelty that was observed before the murder of Kirov, during the period of collectivization and famine. Only gradually, two and a half years later, did a terrible denouement come - the Great Terror of 1937–1938. The murder of Kirov was only one, not the most important and not at all obligatory element of this escalation of state violence,” the researcher notes.

On the other hand, quite fully published and accessible materials about Nikolaev, especially his diaries, allow us to draw some conclusions about the identity of Kirov’s killer. These documents show him as a person who had not only noticeable physical defects (small stature, disproportionate physique, sickness), but also a quarrelsome character, mental imbalance, reaching pathological forms.

Prone to conflict, Nikolaev has been left without work and livelihood in recent months, which has made him even more embittered. At the same time, he remained a member of the party and legally owned a revolver, which he acquired back in 1918. He retained many acquaintances in the regional committee, his wife Milda Draule continued to work there, so it is not surprising that Nikolaev was released as a party member after routine document checking October 15. He also had much more opportunities than a person from the street to penetrate Smolny, where various institutions operated at that time. In addition, not all the stairs in the building were carefully guarded.

As for the death of the guard Borisov, the same Khlevnyuk asks a reasonable question: how could his interrogation by Stalin threaten the conspirators if they acted on the latter’s direct orders? At the same time, the other Kirov guards (there were 15 people in total), including Dureiko, who was in the corridor at the time of the shot, safely survived. The historian admits that Borisov’s death could indeed have been a coincidence.

A special and most mysterious line in the case is the role of Draule. Historian Tatyana Sukharnikova, director of the Kirov Apartment Museum in St. Petersburg, noted, that her figure was almost completely (and clearly not by accident) excluded from the initial investigation. However, it is known that Nikolaev’s wife was interrogated 15 minutes after the murder, that is, most likely, she was also in Smolny at that time. In the article "The death of Kirov: facts and versions”, published in 2005 in the magazine “Rodina” (one of its authors was the same Sukharnikova), presents the conclusions of the Center for Forensic and Criminalistic Expertise of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. The center received items of Kirov's clothing that he was wearing at the time of the murder, as well as documents (certificates, acts) relating to the events of December 1, 1934. The experts' findings cast doubt on some of the claims made in the initial investigation. In particular, questions arise about the version that Kirov was shot while walking along the corridor: at the time of the shot he was probably not in an upright position. In addition, the conclusion states: “During a forensic medical examination of Kirov’s underpants, it was established that in the absence of traces of prolonged wear after the last wash, significant stains of dried sperm were found on the inner surface in the front in their upper part.”

The available materials contain many rumors that circulated in Leningrad immediately after the murder, for example, that the motive for the murder was jealousy, since Kirov was in a relationship with Nikolaev’s wife. At the same time, in Nikolaev’s published diaries the topic of jealousy towards his wife is not touched upon in any way.

Oleg Khlevnyuk comes to the conclusion: “The version of Stalin’s participation in the murder of Kirov is a typical example of a conspiracy theory. It proceeds from the fact that the benefit obtained is the main evidence of involvement. She denies the possibility of accidents and ordinary stupidity. <…> Even if we assume that Stalin really was the organizer of the murder of Kirov, this adds little to the understanding of the history of the Stalin period and Stalin himself. Such a crime could be called the most harmless thing that the Soviet dictator committed.”

Thus, the version of a conspiracy led by Stalin, as a result of which Kirov was killed, looks dubious. It is not confirmed by available documents and was developed during the period of exposure of the personality cult of the Soviet leader. The hypothesis about Nikolaev's personal motives (be it mental instability, resentment towards the party leadership or jealousy), as evidenced by his diaries and research results, is more convincing. However, due to the insufficient volume of documents, some of which are still classified, blind spots remain in the Kirov murder case.

Cover photo: Stalin and Zhdanov at Kirov's funeral. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Read on topic:

- M. Mikhailov. The starting shot of the Great Terror. What did Kirov's murder lead to?

- I. Venyavkin. The cult of Stalin in the USSR

- N. Okhotin, A. Roginsky. The Great Terror: 1937–1938. Brief chronicle

- Did Stalin say: “If there were a man, there would be an article”?

- Is it true that in 1941, on Stalin’s orders, a plane carrying a miraculous icon flew around Moscow?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.