On the Internet you can find a statement that the name of this item of clothing comes from the name of a Russian writer. We checked how valid this claim is.

People also write about the connection between the sweatshirt and Leo Tolstoy. sites, selling clothes, and bloggers (for example, in LiveJournal, in "VKontakte" and on the platform "Zen"). It is alleged that the name was derived from the loose shirt worn by the author of War and Peace.

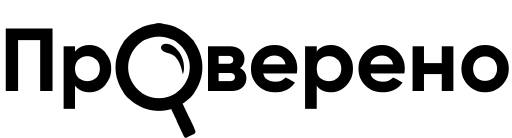

A spacious peasant shirt, tied with a belt, was Leo Tolstoy’s everyday wear. In it, the writer is depicted both in a portrait by Ivan Kramskoy (1873) and in paintings by Ilya Repin (1887) and Mikhail Nesterov (1907).

During Tolstoy’s lifetime, this item of clothing was not called a sweatshirt. Thus, critic Vladimir Stasov in article about Repin’s portrait he used the word “blouse”: “He looks directly at the audience, slightly tilting his powerful head to the side, with a long gray beard, he is wearing a black blouse (in the 1873 portrait he is also wearing a blouse, only blue), the blouse is tied at the waist with a belt, but somehow looks like a cassock.”

At the end of the 19th century, the word "sweatshirt" meant a follower Tolstoyanism - the religious and ethical teachings of Leo Tolstoy, which implied the renunciation of violence against living beings and everyday luxury. For example, it was in this context that Nikolai Leskov used it in the essay “Corral"(1893): "If you think this is, perhaps, according to Tolstoy, then it is so; but in vain he signs for all women. Maybe there are such people, as he says, but for this they had to be disfigured in a special way from childhood. And my daughter, as you can see, is a living and full of life woman, and not a sweatshirt.” Another example of word usage is in his own story “Winter day" (1894): "Yeah, so she's a sweatshirt! Well, it’s okay: I hate all sorts of utopias, but in my opinion, entrusting the servants with non-resistance to evil is even wonderful.”

In relation to the writer’s clothing, the word “sweatshirt” is found in memoirs writer Andrei Bely: “The gray beard became completely white, it thinned out and became smaller; no longer in civilian clothes - in a sweatshirt; sat hunched over in front of his mother.” But Bely wrote the book “At the Turn of Two Centuries” already in 1930, when the word became widespread in everyday life.

“A sweatshirt is the most common type of clothing for Soviet workers,” he wrote in the book “The language of the revolutionary era"(1928) Soviet linguist Afanasy Selishchev. Loose-cut outerwear, belted with a belt, was perceived as a symbol of revolutionary simplicity, contrasted with old-regime frock coats and tailcoats. He writes about this in detail in the story “Grand slam"(1934) Boris Pilnyak: “Human clothing was restructured not only because braid, gold and insignia disappeared, but because it was more decent to be dressed inconspicuously, sparsely, poorly, the red scarf and brown sweatshirt, boots, cap began to flow on an all-Union scale - the cap disappeared along with the hat.” In the story by Evgeny Zamyatin “X"(1919) a burgundy sweatshirt converted from a cassock is a key image in the description of the tragedy of a deacon looking for his place in a new life: “I would cross myself, but I can’t: from his corner the deacon sees that he is not wearing a cassock, but a burgundy sweatshirt.” In Soviet literature of the 1920–1930s, this is, although simple, but everyday clothing: accountant Berlaga is also wearing a sweatshirt in “Golden calf", and the poet Bezdomny in "The Master and Margarita"

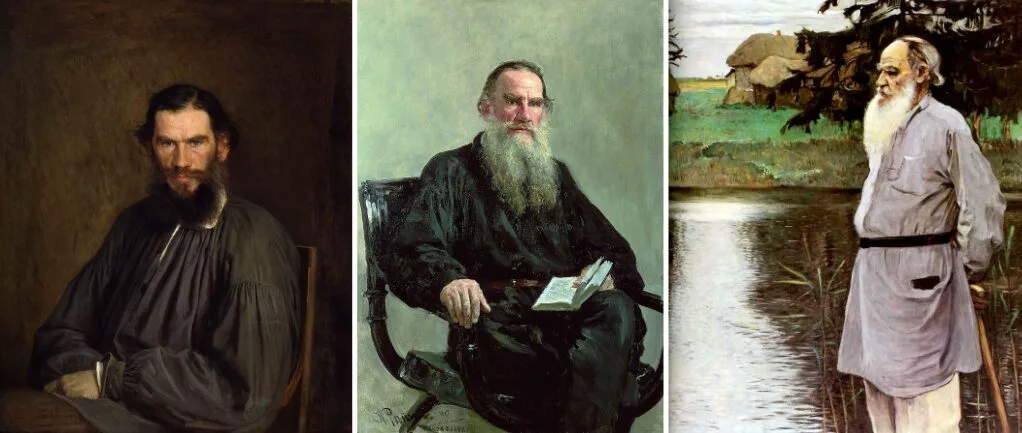

However, the Soviet sweatshirt was different from Tolstoy’s peasant blouse. By the mid-1920s, this was the name for an outer shirt of a semi-military cut, and only the length and the indispensable belt reminded of the clothes the writer wore.

And ten years later, the sweatshirt went even further from the original design and began to look more like a French jacket.

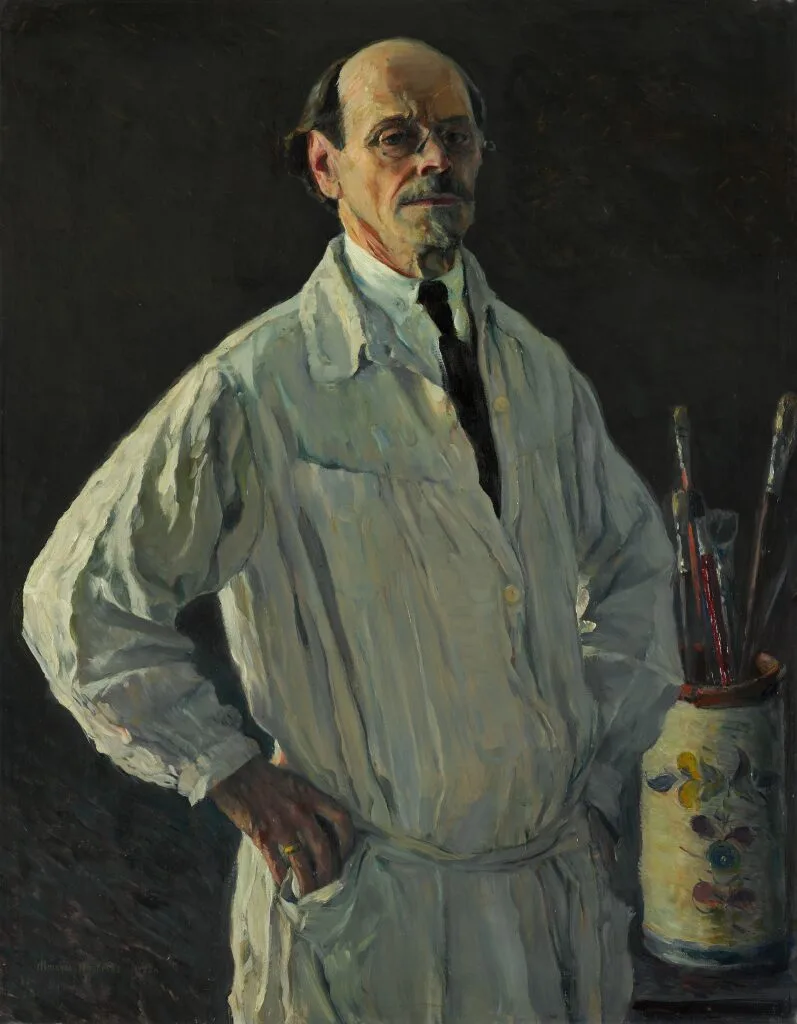

Only one style was similar to a traditional sweatshirt - the “artist sweatshirt,” which painters often used as a work blouse.

Deliberate simplicity in clothing gradually went out of fashion back in the late 1920s. In 1927, in the poem “Stabilization of life» Vladimir Mayakovsky condemned the return to pre-revolutionary style, mentioning the sweatshirt:

I suggest

so that this ideological fight

did not continue pointlessly,

sew

for sweatshirts

tailcoats

and wear

patent leather sandals.

Nadezhda Mandelstam in her memoirs described this process as follows: “You were no longer supposed to walk around in rags and you had to have a completely gentlemanly appearance in order to go to the editorial office or the film committee. The jacket and sweatshirt of the Komsomol members of the twenties have finally gone out of fashion - “everything should look the same.”

By the 1940s, sweatshirts had practically disappeared from everyday life. The word returned in the 1990s as a designation for a loose, soft sweater with a hood. In the Kommersant newspaper in 1992 it was written in quotation marks, and in 1993, when the use apparently became more frequent and familiar, - already without them. The term became an analogue of the later English "sweatshirt" and "hoodie", and the word was apparently chosen for its loose fit, reminiscent of the original sweatshirts.

Cover photo: Ilya Repin. Plowman. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy on arable land. 1887. Tretyakov Gallery

Read on topic:

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.