According to the widespread version, in Russian money received its slang name thanks to banknotes with the image of the Russian Empress. We decided to check whether historical sources confirm this.

A statement about the connection between the etymology of the word “grandmother” and the portrait of Catherine II on money can be found, for example, in social networks and on blogging platforms, on the portal Pikabu, V popular science articles and on the website "History.rf" Most often, authors write that the slang word owes its origin to the image of the Empress on the 100-ruble banknote.

In literature, the earliest mention of the word “grandmother” in the meaning of “money”, judging by National Corpus of the Russian Language, dates back to 1844. In the story by Vladimir Dahl “Petersburg janitor“There is a passage describing the jargon of the capital’s scammers: for example, “getting a tag” meant getting a passport, “stealing a bench” meant stealing a horse. It also talks about money, when a gang of pickpockets asks the hero how much he stole: “Gregory answered calmly: “Grandma, freckles and stucco,” that is, money, a watch and a handkerchief; and the scammers looked at Gregory in bewilderment, not knowing whether he was a mazurik, that is, a comrade, or a traitor.”

Five years later, Ivan Kokorev’s essay “Small industry in Moscow”, in which the author writes about the dark side of city life: “We would listen to the speeches of the local inhabitants, calling each other physicists, mechanics, cutters, and in a contemptuous sense - seven-kopeck swindlers, mazuriks; they would know what a lafa, a stirrup means, what a rooster is, what kind of thing a grandmother is, and how a bumblebee bites.” And in the notes he explains: ““Lafa” is a gain, “strema” is a failure, “rooster” is a watchman, “grandmothers” is money, “bumblebee” is a wallet.” So in the 1840s, the word “grandmother” already existed as a slang term for money and was common in both St. Petersburg and Moscow.

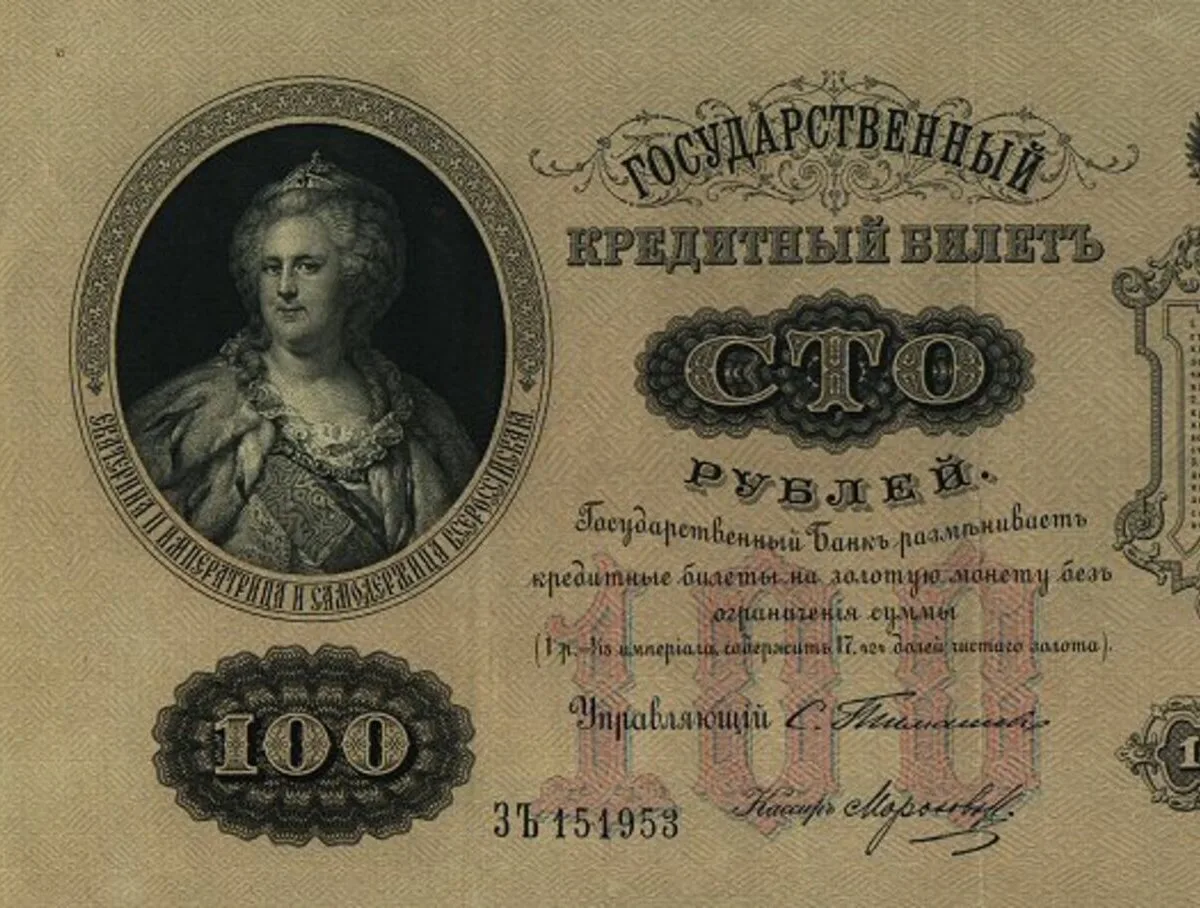

Paper money in Russia was actually introduced into circulation by Catherine II. December 29, 1768 (January 9, 1769 according to the new style) empress signed the manifesto on the establishment of two banknote banks - in St. Petersburg and Moscow, which received the right to issue banknotes that circulate on a par with coins.

To avoid counterfeiting, the banknotes were marked with watermarks: the coats of arms of the four kingdoms (Astrakhan, Kazan, Siberia and Moscow) and inscriptions - as well as two oval seals in the middle of the sheet. Catherine II was not depicted on these banknotes. The design of banknotes continued to be quite laconic: for example, at the beginning of the 19th century they depicted a double-headed eagle.

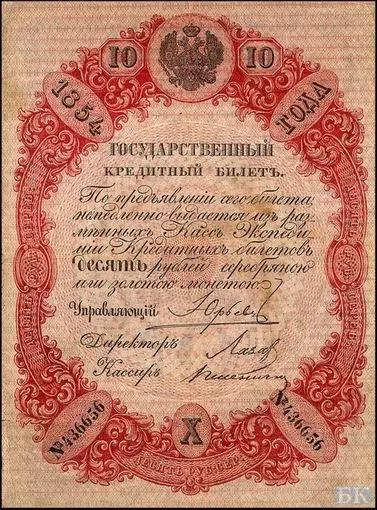

After reforms, carried out by the Minister of Finance Yegor Kankrin, in 1840 banknotes were replaced by banknotes. But Catherine II was not there either.

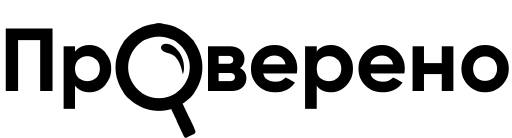

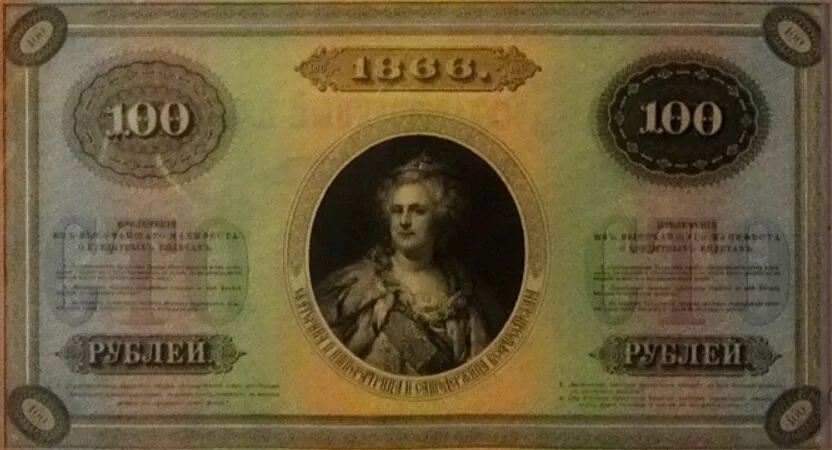

The empress's portrait appeared on banknotes only 100 years after her manifesto. In February 1868, the Senate issued a decree introducing a new type of tickets into circulation, and in March the exchange of old tickets for new ones with a denomination of 25 rubles began. A year later, in March 1869, the remaining denominations, from 1 to 100 rubles, came into circulation. On the 5-ruble ticket was depicted Dmitry Donskoy, on the 10-ruble note there is a king Mikhail Fedorovich, on 25-ruble - Alexey Mikhailovich, on 50-ruble - Peter I. Finally, a portrait of Catherine II was placed on the 100-ruble ticket.

Subsequently, behind the hundred-ruble banknotes entrenched The name is “katenka”; babka was the name given to any money, regardless of its denomination.

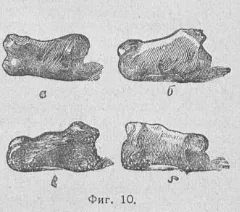

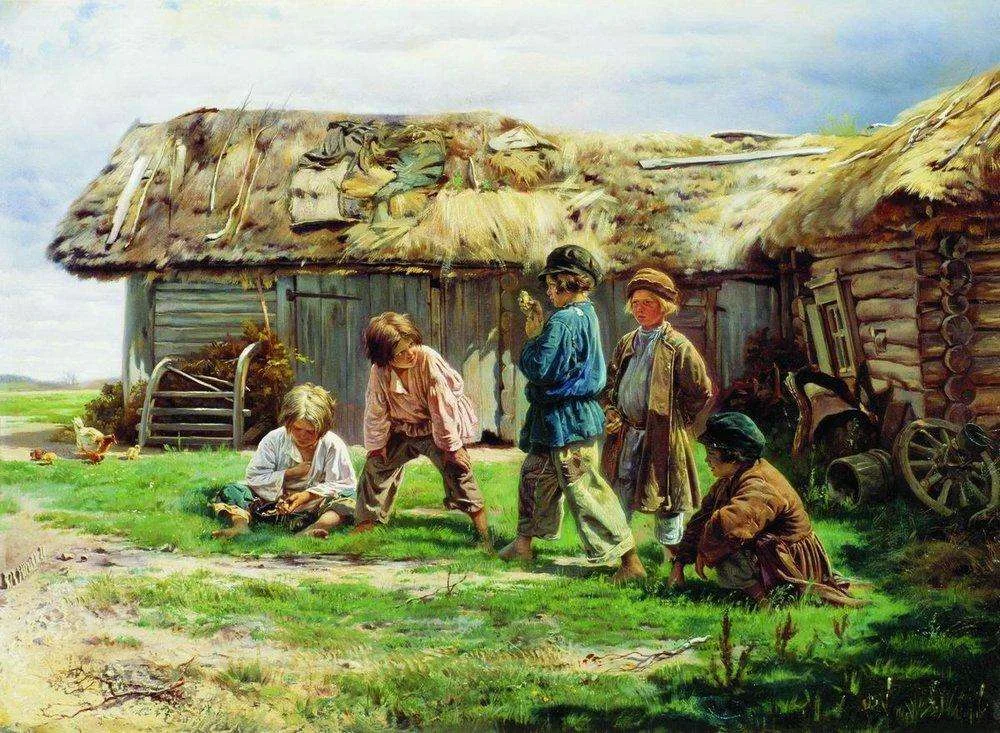

The most likely origin of the slang word is from the popular grandma games. Ethnographer and folklorist Ivan Sakharov in the book “Tales of the Russian people"(1836) writes: “In Russian family life, this game occupies the most honorable place, and there is no place where it does not exist.” A necessary element of the game is the pasterns themselves, that is, beef hoof bones. They were placed in a certain way (depending on the type of game), the striker had to knock out the maximum number of knuckles with a weighted bone. As the researcher writes, the extraction, exchange and sale of money for boys constituted a “special type of industry” with its own exchange rate. The largest bones (cue balls), as well as the headstocks, filled with lead for weight (svinchatki) were especially valued.

Source: Wikimedia Commons / Tretyakov Gallery

Most likely, the slang term for money arose precisely by analogy with the popular game - for many, since childhood, grandmothers were actually the monetary equivalent. The version about the portrait of Catherine II is much less plausible: it does not appear in the literature of the 19th century, and the banknote itself with the image of the Empress appeared only in the second half of the century, when money was already called babka.

It can be assumed that the name is associated with silver or gold coins minted under Catherine, on which the empress’s profile was depicted. But this is also unlikely, since no traces of the spread of the slang word in the 18th century could be found. The coins were named by their denomination (nickel, ten-kopeck piece, two-kopeck piece, etc.), but not by the name of the ruler.

Cover photo: Bank of Russia

Read on topic:

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.