It is widely believed that the Russian emperor, who died in 1825, actually faked his death and began to live as a hermit far from the capital. We tested the validity of this theory.

The version that Alexander I, contrary to official reports, did not die in Taganrog on November 19 (according to the modern Gregorian calendar - December 1) 1825, but lived secretly for many years in Siberia under the name Fyodor Kuzmich, began to spread already in the middle of the 19th century. Initially, its main adherent was the Tomsk merchant Semyon Khromov, whose “Notes"remain the main source of information about the identity of the mysterious old man. Since the 1880s, despite attempts opposition from the tsarist government, articles and books devoted to this theory began to be published. The most detailed arguments in favor of the increasingly widespread version were presented in the book of Prince Vladimir Baryatinsky “Royal Mystic"(1913). Was interested the personality of Fyodor Kuzmich and Leo Tolstoy.

In the 20th century, among the supporters of the version that the elder was Alexander I, who faked his death, were the journalist and art critic Lev Lyubimov, the historian Nathan Eidelman, and many authors of the Russian emigration. Already in the present century in favor of this theory spoke out Director of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences and author of popular school textbooks in Russia Andrei Sakharov. Publications about the connection between the Siberian elder and the Russian emperor are easy to find in Media and in blogs, and references are in popular culture (for example, in the series “Karamora").

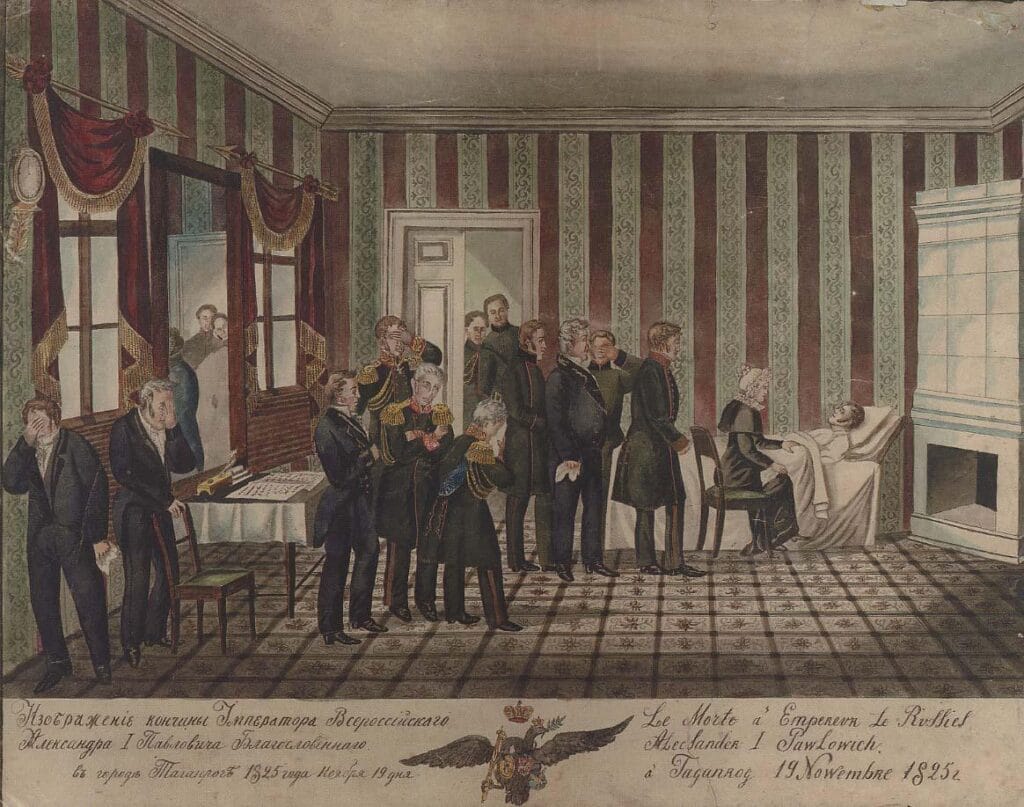

Rumors about the posthumous fate of Alexander I appeared almost immediately after the announcement of his death and long before the first reliable evidence of Fyodor Kuzmich. This was facilitated by the extraordinary circumstances of the incident: the emperor died in provincial Taganrog after a sudden illness, although the monarch, not yet old (47 years old), had not complained about his health. Contributing to the general confusion of minds was the confusion over which of Alexander's brothers, Constantine or Nicholas, would inherit the throne, as well as the failed Decembrist uprising. According to one story, Alexander I was killed (poisoned, stabbed, etc.), according to others - “sold into foreign captivity” or “left on a light boat at sea.”

However, none of the numerous doctors and courtiers who were next to the emperor at his death ever spoke out against the official version. The argument that the coffin was closed for a reason during the funeral is refuted by the understandable decision of the organizers of the ceremony - embalming the body to be sent to St. Petersburg passed unsuccessfully, and the facial features of the corpse began to deform. As for the allegations that the tomb of Alexander I in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1921 was opened and turned out to be empty, it was convincing refuted chief researcher of the Museum of the History of St. Petersburg Marina Logunova. Of course, only the exhumation of his remains can challenge the official version of the death of Alexander I, but it was not carried out and it is unclear whether it will ever be carried out in the future.

Against the fact that Alexander I faked his death, testifies and the ensuing succession crisis mentioned above. Back in 1823, the Emperor signed a secret manifesto on the transfer of the throne not to the eldest of his brothers, Konstantin, but to the middle one, Nicholas. But even Elizaveta Alekseevna, the widow of Alexander I, and his closest advisers (for example, Field Marshal Ivan Dibich and Prince Pyotr Volkonsky) considered Constantine to be the heir. It is strange to assume that, while preparing his imaginary death, the monarch did not initiate his entourage into plans for succession to the throne.

As for the mysterious old man Fyodor Kuzmich, his existence is beyond doubt. For the first time in surviving documents, he mentioned in the fall of 1836, when he was detained in the Krasnoufimsky district of the Perm province. During interrogation, the elder stated that he did not remember his “ancestry from infancy, named Fedor Kozmin, son Kozmin, 70 years old, illiterate, Greek-Russian confession, single.” As a tramp, he was sentenced to 20 lashes and exile to Siberia. Initially, Fyodor Kuzmich was assigned to the village of Zertsaly, Bogotol volost, Tomsk province, where he arrived on March 26 of the following year. In 1849, he settled near the village of Krasnorechenskoye on the Chulym River, and at that time his figure began to attract the attention of local residents, although at that time he was not mistaken for the abdicated tsar. After wandering around different places in 1858, Fyodor Kuzmich, at the invitation of the merchant Khromov, moved to a farmstead that belonged to him near Tomsk (now the village of Khromovka within the city), where he lived until his death on January 20 (February 1), 1864.

The elder is not mentioned in official documents after 1837, and in the memories of him left by Khromov and other people who knew him, it is not easy to separate truth from fiction. However, all the evidence indicatethat Fyodor Kuzmich belonged to the upper strata of society, knew court life and was almost certainly a military man who participated in the Patriotic War of 1812, as well as foreign campaigns of 1813–1814. It is also very likely that he at one time participated in the Masonic movement, widespread among the Russian nobility in the first half of the 19th century. This is also indicated by the so-called secret of Fyodor Kuzmich: two notes on narrow paper strips, kept in a bag, which the elder allegedly pointed out to Khromov before his death. The text on both was most likely written in code. There is no single version of its decoding, and the situation is aggravated by the fact that the original notes are lost; they are now known only from imperfect photographs. Nevertheless there is grounds see in them parallels with the ciphers used by the Freemasons. Other probable examples of Fyodor Kuzmich’s handwriting are also known: an envelope inscribed by him and a copy of extracts from the Bible he made. In 2015, graphologist Svetlana Semyonova stated, that her analysis showed: the handwritings of Alexander I and Fyodor Kuzmich belong to the same person. However, this study has not been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, and there are reasonable doubts about its scientific validity.

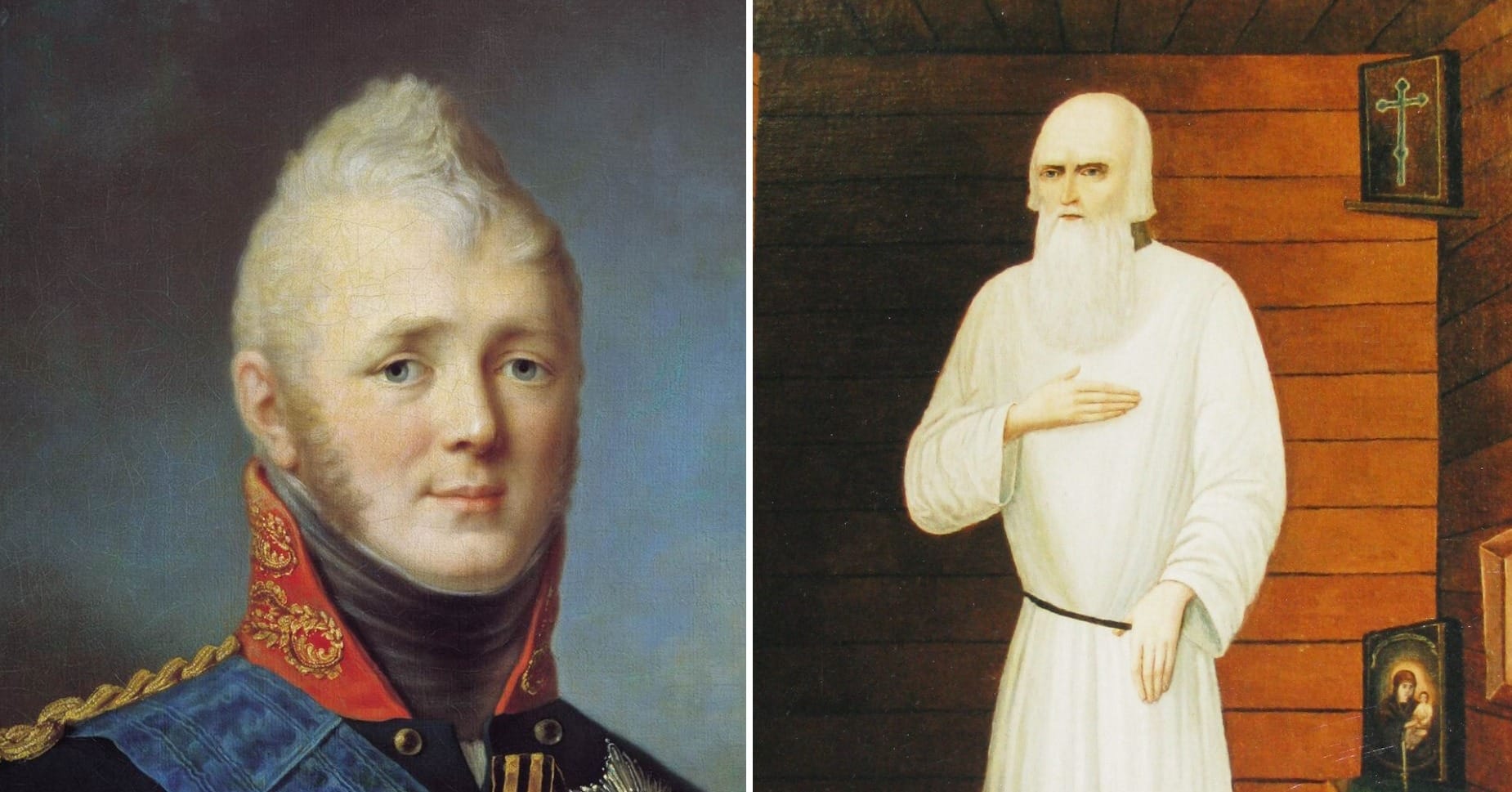

No lifetime images of Fyodor Kuzmich have survived. Posthumous portrait, made by order of Khromov and widely known in reproductions, has an obvious resemblance to Alexander I. However, there is another, very different drawing, the author of which captured the old man on his deathbed. This image, according to some testimony from contemporaries, more accurately conveys his appearance. Verbal descriptions of Fyodor Kuzmich also have some contradictions with the appearance of the emperor. In particular, the old man had an aquiline, slightly predatory nose, and his head retained (at least until 1862) curly light brown and gray hair. At the same time, it is known that Alexander I’s nose was straight and that by the end of his life the emperor was almost bald.

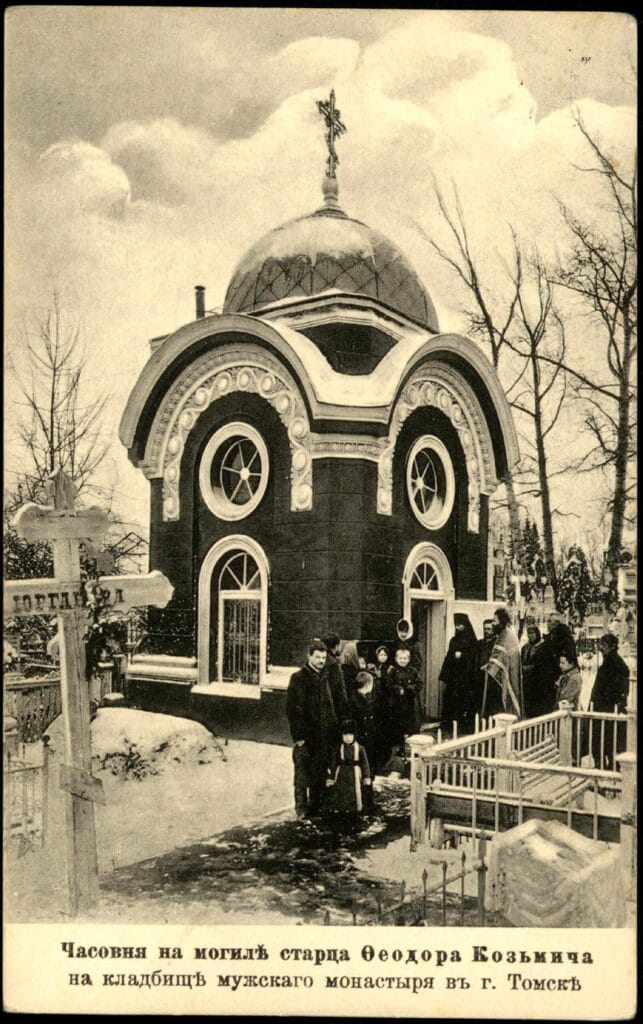

A kind of cult quickly arose around the grave of Fyodor Kuzmich in the Tomsk Alekseevsky Monastery - in 1904, a chapel was consecrated on this site and the remains of the elder, which remained incorrupt, were allegedly found. After the revolution in 1936, the chapel was destroyed and a cesspool was built in its place. However, popular veneration of the elder remained, and in 1984 the Russian Orthodox Church canonized him as the righteous Theodore of Tomsk. In 1995, on the site of the cesspool, excavations, in which they discovered a coffin without a lid with bone remains without a skull. They were declared the relics of the saint and placed in the monastery cathedral. No genetic research has been carried out on these remains. However, there is no unconditional evidence that they belong to Fedor Kuzmich.

Versions about the origin of the mysterious old man are not limited to Alexander I, who decided to fake his death. For example, spoke out assumptions that the nobleman Fyodor Uvarov, who went missing in St. Petersburg in 1827, was hiding under the name of Fyodor Kuzmich. To others candidate was the alleged illegitimate son of Emperor Paul I, who served in the Russian fleet under the name Simeon Afanasyevich the Great and was said to have died in a shipwreck in 1794. However, none of these hypotheses has any reliable evidence.

There is also a lesser-known legend that Elizaveta Alekseevna also did not die, as announced, in May 1826, but from 1841 to 1861 lived in the Syrkov Monastery in the Novgorod region under the name of Vera the Silent. In this case there are direct evidencethat it was not the Dowager Empress, but the youngest daughter of Major General Alexander Butkevich.

The legends themselves about a monarch who is considered dead, but in fact continues to live, are known about a number of medieval rulers: the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson, German Emperor Frederick II Staufen, Portuguese king Sebastians etc. Numerous cases of impostors posing as the late monarch, which were especially common in Russia in the 17th–18th centuries, are of a similar nature.

So, there is not a single clear argument in favor of the fact that Elder Fyodor Kuzmich is Emperor Alexander I. This version could only be finally confirmed or refuted by the opening of the tomb of Alexander I in the Peter and Paul Cathedral and the study of the supposed relics of Theodore of Tomsk, but both of these events seem unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Cover photo: S. Shchukin. Portrait of Alexander I (left). Unknown author. Portrait of Elder Fyodor Kuzmich (right). Via Wikimedia Commons

- Arzamas. Course of lectures “Impostors and Troubles”

- S. Korolev. Immortality of the ruler. Lenin as a fairy-tale character

- B. Gloger. Emperor, God and Devil: Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in History and Legends

- Is it true that Dumas the Father is Pushkin who faked his death?

- Did the Decembrists really convince the rebel soldiers that the Constitution was the name of Konstantin Pavlovich’s wife?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.