Information that the Third Reich mass-produced soap from human fat is extremely widespread both on the Internet and in book publications. We checked whether this statement is supported by facts.

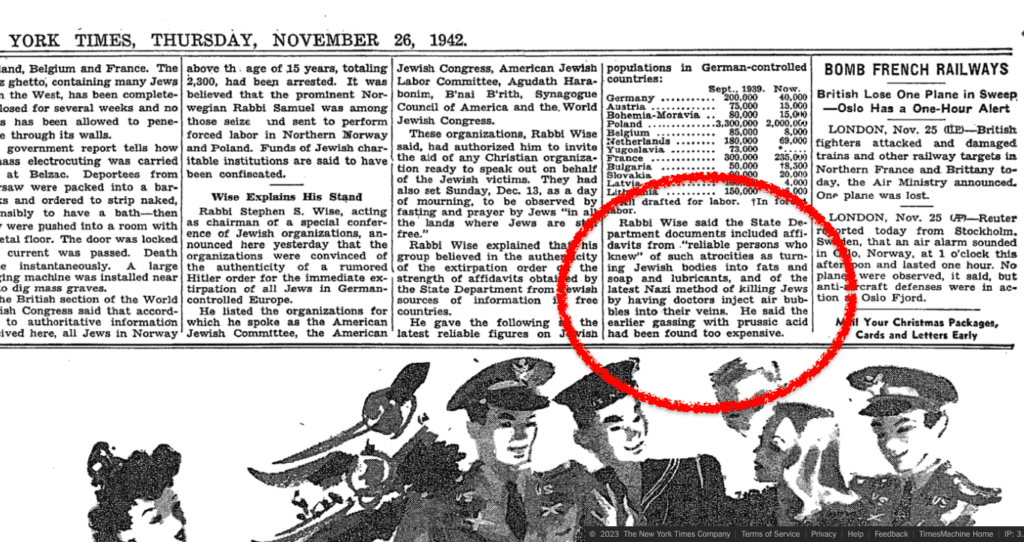

Reports of Nazis making soap out of people appeared already in 1941, including in American intelligence reports (with reference to reports from local residents). In 1942 from the pages Chicago Tribune And The New York Times the leader of the US Zionist movement, Dr., speaks about making soap from corpses Stephen Samuel Weiss.

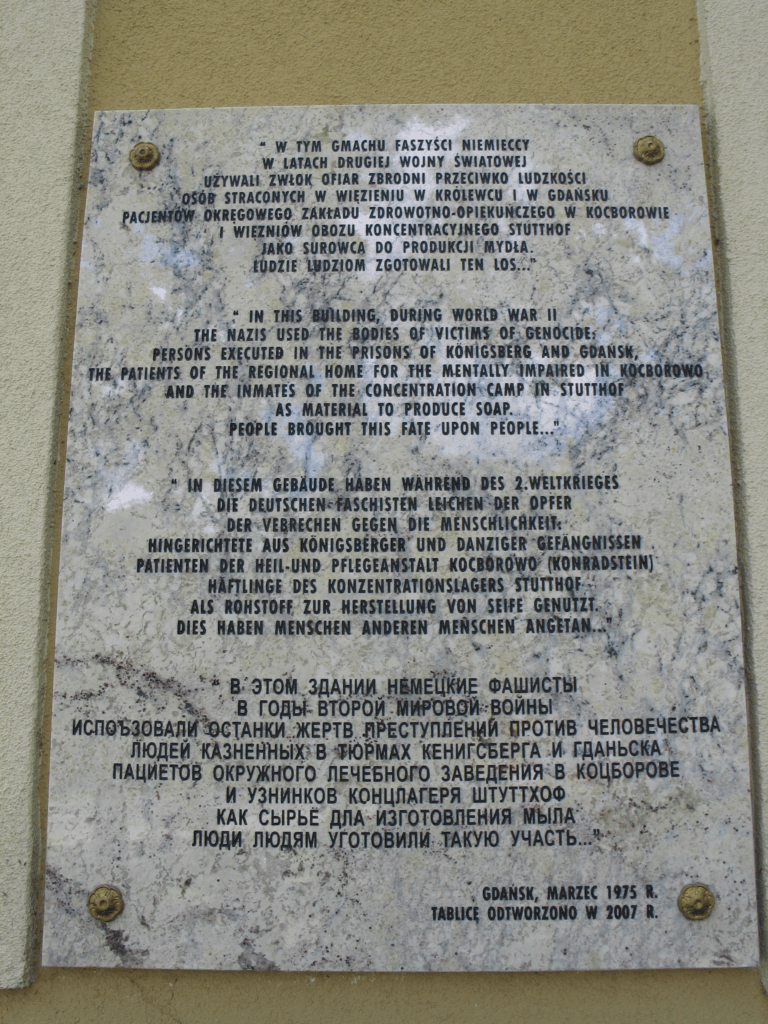

In 1945, the story of Nazi soap production in a laboratory in Danzig (Gdansk) describes Polish publicist Zofia Nalkowska. After the city was captured by the Red Army, the Polish authorities sent two doctors to investigate the laboratories of the Anatomical Institute of the Danzig Medical Academy, which, in particular, produced teaching aids using the internal organs of executed criminals. Here's how describe examination by anthropologists Alexandra Arkhipova and Joseph Zislin: “They see a terrible picture: body parts with traces of medical operations are scattered everywhere. In addition, they saw tanks there and a white mass similar to fat, which one former worker, a Pole, said was “soap made from people.” The doctors verbally reported this to the authorities, but no written report was presented on their behalf at the Nuremberg trials.

This and other evidence was presented in Nuremberg on February 19, 1946 by the assistant to the chief prosecutor from the USSR L.N. Smirnov. He reported that the institute had already carried out “semi-industrial scale experiments in obtaining soap from human bodies and tanning human skin for industrial purposes,” and presented a sample of human fat soap found in a laboratory. Smirnov's speech was based on the testimony of the institute's laboratory assistant, the Pole Zygmunt Mazur, who said that in 1944, Dr. Rudolf Spanner (a famous pathologist and director of the Anatomical Institute) conducted experiments with making soap from human ingredients. In particular, Mazur (who died of typhus in prison before reaching the tribunal) gave a recipe for the production of this soap: “This recipe required taking human fat, 5 kilos with 10 liters of water and 500 [grams] or a kilogram of caustic soda. Cook all this for two to three hours, then let cool. The soap floats to the top, and the residue and water remain at the bottom in the buckets. Table salt (a handful) and soda were also added to the mixture. Fresh water was then added and the mixture was cooked again for two to three hours. After cooling, the finished soap was poured into molds.”

From then until the early 1990s, this plot was reproduced as absolutely reliable in the media, literature and oral narratives along with other Nazi crimes. In particular, books and diaries by Zofia Nalkowska describing what she saw in Gdansk were published and studied in Poland and abroad - for example, published already in 1945 essay “Professor Spanner,” which describes in detail the “history of the soap factory” and Mazur’s first testimony, has gone through more than one reprint.

One of the first to publicly talk about the inconsistency of the soap story stated Michael Berenbaum, curator of the creation of the United States Holocaust Museum and its first director (from 1993 to 1997). When Berenbaum began collecting museum artifacts, he said, he thought it was obvious that the Nazis were making soap from human fat. There was probably an ethical question whether to use soap at the exhibition. However, after careful research, Berenbaum "found evidence of everything else the Nazis did and worse," but there was insufficient evidence of soap production and it was not included in the exhibition. The fact that the industrial production of soap from human fat is a legend in 1990 wrote researcher Yehuda Bauer, and about this with some regularity Representatives of Yad Vashem (the Holocaust memorial complex) also say. All this has prompted chemists, biologists, historians and anthropologists to study the issue in more depth over the past 30 years.

Anthropologists and historians separately note that the plot with human soap appeared during the First World War, not least thanks to British propaganda. In 1925, it was debunked by the British themselves, but became stable far beyond the borders of Great Britain. As researchers Arkhipova and Zislin write, “through the joint efforts of the media, propagandists and folklore tradition, the story of hostile social groups that are capable of turning people into soap spread widely in Europe and Russia in the 1920s and 1930s. In the early 1920s, residents of Petrograd accused the local Chinese of stealing people for soap. The young writer M. Stronin mentions this incident in a sketch from the life of St. Petersburg punks: “The Chinese boiled the old man into soap"Thus, by the beginning of the Second World War, all the conditions were created for a second, very similar plot to appear: soap made by the Nazis from Jews." You can read in maximum detail about the history of this plot in article "The Funeral of Soap: Legends and Reality of the Holocaust."

Perhaps the most thorough at the moment is study available evidence, including photographic documents and interrogation texts, of the Polish historian Joachim Neander. The study was published in 2006 and showed shortcomings in the work of the Polish commission, of which Zofia Nalkowska was a member, the lack of sufficient material evidence and a number of inconsistencies in Mazur’s evidence. In particular, the soap production recipe he described was not only outdated, which is strange for the fairly technologically advanced Germany of that time, but also dangerous for human use (although Mazur showed that he himself washed himself with it). In addition, Spanner's case was investigated in Britain and Germany, and he himself was interrogated three times in 1947 and 1948. The court and investigation did not find sufficient evidence of guilt, concluding that he was engaged exclusively in “experiments with dead bodies.” In addition, post-mortem analysis showed that there were no Jews among them, the bulk of the bodies were supplied to the academy from prisons and homes for the mentally ill, and most of them were ethnic Germans and Poles. The authors came to the same conclusion post-mortem investigations, conducted in 1967–2002. As a result, Spanner was not convicted and spent the rest of his life in Cologne as a university professor.

Chemical and DNA analysis of available samples of soap produced industrially in the Third Reich, doesn't show anomalies or the presence of an amount of human DNA that could be considered evidence of the production of soap from human fat. But here it is worth noting that during the dissection of corpses and the preparation of anatomical aids, an unrefined soap mass is actually formed, which is used to work with the joints of anatomical aids - Spanner spoke about this in all his testimony. From this Joachim Neander made two assumptions. First: it was this foul-smelling substance that was eventually called soap; it is probably this soap that Yehuda Bauer has in mind when talking about “25 kg of soap produced in Danzig.” Second: in theory, given the shortage of soap, this mass could be cleaned in the laboratory and used for household needs - washing tables and rooms. Both assumptions were confirmed in 2006.

IN statement The Main Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against the Polish People of October 13, 2006 states that no crimes were committed on the territory of the Medical Academy in Danzig, in particular, the use of corpses from the concentration camp is not confirmed. However, during the investigation, which began in 2002, an analysis was carried out of a bar of soap stored in The Hague and a bar of soap given to journalists by a former employee of the academy. Professor Andrzej Stolychwo, who specializes in the chemistry of fats, said that the abrasive kaolin was added to the soap, making the soap suitable for household purposes, and almond oil to reduce the smell. And the analysis suggests with a high probability that the composition contained not only animal fats, but also human fat, which, according to Stolykhvo, is a violation of ethical principles.

November 20, 2006, prosecutor Pyotr Nesin from the Institute of National Remembrance stopped investigation for lack of evidence of a crime. He found no evidence that Spanner instigated the murders in order to obtain corpses for the Academy. The final verdict states that in 1944 and 1945, Spanner's laboratory extracted "a chemical substance essentially soap" from human fat.

Released in 2010, a study by Monika Tomkiewicz and Peter Semkov dedicated to Spanner also analyzes chemical data and comes to the conclusion that it is unlikely that Spanner, with his education and status, was interested in the processing of corpses other than the preparation of anatomical manuals. But with or without his knowledge, it is likely that some soap was actually produced in the laboratory. However, the authors criticize the results of Andrzej Stolychwo's 2006 analysis because they were not published in detail, and DNA analysis of the same soap samples carried out at the beginning of the investigation (in 2002) did not show the presence of human DNA. Nevertheless, Tomkiewicz and Semkov agree with Neander that against the backdrop of a legend that had already existed for several decades and a very real genocide, as well as information that became available about inhumane experiments, it was the finds in Gdansk that became the basis of the myth about Jewish soap.

All researchers, as well as employees of memorials emphasize the danger of spreading this story, as it could fuel Holocaust denial. Aaron Breitbart, employee Simon Wiesenthal Center (a Jewish non-governmental organization named after famous "Nazi hunter") spoke the following: “The Holocaust revisionist point of view is that if you can prove something is wrong, then everything [else] is wrong. This gives them the opportunity to question the overall historical accuracy of the Holocaust." And the researchers are right: it is precisely debunking the myth about soap production took as the main argument, the famous Holocaust denier, German chemist Germar Rudolf, after failed his campaign to deny the Nazis' use of gas chambers.

Thus, the widespread story of soap making from human fat arose during the First World War and was soon refuted, but continued to exist in folklore. Against the background of the crimes of Nazi Germany, the plot was transformed, was picked up at the official level and was disseminated as an undeniable truth until the 1990s. There are a number of reasons to assert that in Dr. Spanner’s laboratory, a by-product of the preparation of anatomical preparations was used, among other things, to make laundry soap. However, the industrial production of soap from human fat is not supported by historical evidence and is refuted by all modern research.

Not true

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.