The story of Pope Joan, a woman who became pontiff, is one of the most common legends about the Middle Ages. Until now, many people pass it off as reliable. We decided to check whether Pope Joan existed.

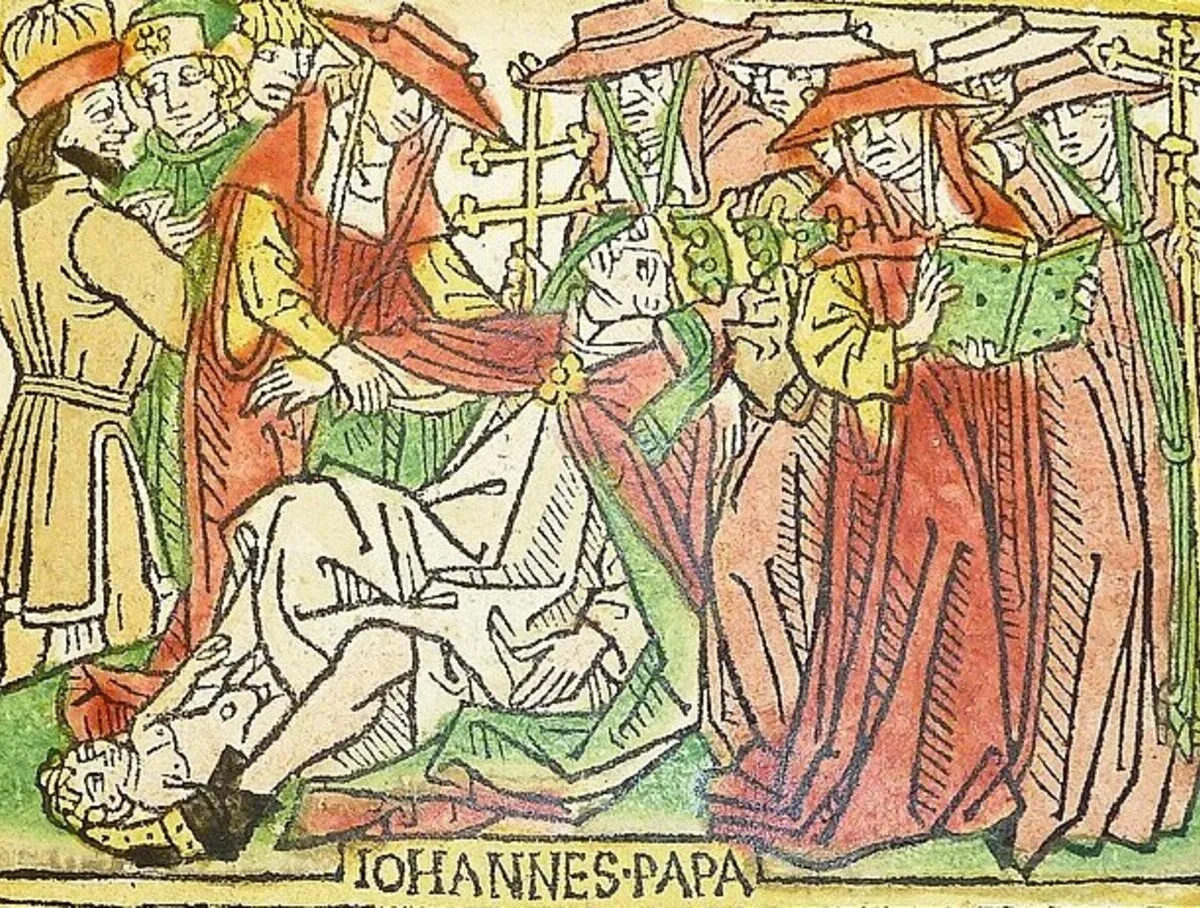

The legend of Pope John did not lose its popularity either in the Middle Ages or in modern times; it still appears in blogs and on historical sites. Giovanni Boccaccio wrote about her in the book “About famous women"(1361), in the 20th century they filmed about a woman on the papal throne movies, in our time dedicated to Pope Joanna articles on popular sites.

The earliest mention of the story of the pope dates back to the middle of the 13th century. The Dominican monk Jean de Mailly left in his fields chronicles, compiled in 1250–1254, the following note: “Check. There is a story about a certain pope, or rather popess, since she was a woman; Having dressed as a man, she became, thanks to her talent, a notary of the Curia, then a cardinal and, finally, a pope. One day she was riding a horse and at that moment she gave birth to a child. They tied her legs and dragged her tied to a horse's tail; For half a mile, the crowd threw stones at her and beat her to death, and buried her where she died. And on the tombstone they wrote: “Petre pater patrum papissae prodito partum” (“O Peter, father of fathers, expose the birth of a son by the pope”).” In the chronicle of Jean de Mailly there was no dating of this legend, and marginal notes were left on the pages describing the events of the late 11th century.

Then the story began to spread: in total, researchers counted more than a hundred mentions in medieval sources, that is, from the chronicle of de Maia to 1500. Among them Chronica Minor, compiled by the Franciscans at Erfurt around 1261, and "Chronicle of Popes and Emperors» Archbishop Martin of Opava (1277). Later sources, as a rule, copy with minor changes the legend as presented by Martin Opawski: a certain woman named Joanna, born in Mainz in the family of an English missionary, fled with her lover to Greece, where she received spiritual education, posing as a man. Next, a brilliant career awaited her, which culminated in the papacy. Moreover, they elected Joanna unanimously thanks to her intelligence and knowledge. Then, according to Martin Opawski, she began to give birth right during the solemn procession and died from birth pangs. The chronicler even clarifies when exactly the pope ruled - immediately after Pope Leo IV, that is, after 855. And her pontificate lasted about two and a half years.

Later, the story of Pope Joan was used in religious polemics as arguments against the Catholic Church. For example, this legend is mentioned by the predecessor of the Reformation, the English religious philosopher John Wycliffe. In the essay "About papal power"(1382) he clarifies that at birth Pope Joanna bore the name Anna. And a follower of Wycliffe, the Czech reformer Jan Hus, who was burned in 1415, in his book “About the church"Calls the woman-dad Agnes.

Over time (and with the advent of each new version), more and more details became available. If the first chroniclers could not give either the name of the pope or the dates of her pontificate, then later authors already added details. If we summarize the versions, it turns out that Pope Joan ruled either between Popes Leo IV (pontificate years 847–855) and Benedict III (855–858), or between John VIII (872–882) and Marinus I (882–884). At the same time, medieval chronicles do not record two-year intervals between pontificates, which could accommodate the reign of the pope.

The circumstances of the election of Benedict III in 855 in detail described: Emperor Louis II opposed the choice of the Roman Curia and placed his protégé Anastasius on the Holy See instead of Benedict III. But after a few weeks, Anastasius was forced to abdicate (he went down in history as another antipope, that is, not recognized by the church). Well, in the second case election Marina I happened on the same day that his predecessor John VIII died - precisely in order to avoid the intervention of the emperor.

Historians have not yet discovered any other traces of the existence of Pope Joan, except for records in chronicles almost four centuries after the alleged scandal. For centuries, the only evidence was the procedure for checking the sexual characteristics of the future pope, which was allegedly carried out so that the embarrassment with the election of Joanna would not be repeated. First about this wrote Benedictine monk Geoffroy de Courlon in 1290. According to him, the pope sat on a special chair, and one of the cardinals checked whether all the necessary organs were in place.

Girolamo Arnaldi, one of the largest medievalist historians, a specialist in the history of the popes, notes, that only three similar chairs have survived, two of which were made in Antiquity and were intended for ablution or childbirth. And the third really belonged to the popes, but was used not for ceremonies, but for the fulfillment of natural needs. None of the numerous evidence of this unusual ritual was written by direct participants in the enthronement; they are all based on rumors, Arnaldi notes. Therefore, the procedure for feeling the male genital organs of the popes is most likely the same legend as the story of the silver hammer, which is supposedly used to hit the pontiffs on the forehead after death.

None of the authoritative historians doubt that Pope Joan is a legend not supported by facts. Therefore, the debate is mainly about the circumstances under which this myth appeared. Back in 1602, Cardinal Cesare Baronio suggestedthat the legend casting a shadow on the Holy See was created in the middle of the 9th century by the Patriarch of Constantinople Photius, struggling for influence in Christendom with Pope John VIII. According to Baronio, Photius's goal was to cast doubt on the masculinity of the pontiff.

At the same time, the already mentioned Girolamo Arnaldi believes this version is untenable. He cites as an example another legend, known from Pope Leo IX, about the patriarchess - a woman who became the Patriarch of Constantinople. The legend arose during the most difficult period of relations between Rome and Constantinople, shortly before the Great Schism - the schism that finally divided the Eastern and Western churches in 1054. As Arnaldi believes, Patriarch Michael Cerularius, reacting to allegations about the patriarchess, would certainly have recalled the pope if such a story existed. But the first mention of Joanna appeared only two centuries later.

Why the legend of the pope arose in the 13th century and which of the popes this story was directed against is still unclear. Many researchers converge in the opinion that the legend could have arisen in the 10th century, during the period of pornocracy - era of decline Roman Church, when popes surrounded themselves with numerous mistresses and illegitimate children. Then, perhaps, the story about the pope became an urban legend, and the first chronicler Jean de Mailly heard it from someone (noting in the manuscript that the information had yet to be verified). And only then the legend spread in numerous retellings and became a tool of polemicists - from Wycliffe, Hus and Luther to the anti-clericals of the 19th century.

Cover photo: Illustration from the German edition of “On Famous Women” by Giovanni Boccaccio, 1474. Source: Wikimedia Commons/British Museum

Misconception

- L`Histoire. La vraie histoire de la papesse Jeanne

- Is it true that after death the Pope is hit on the forehead with a silver hammer to make sure he is dead?

- Is it true that the Pope in Raphael’s painting “The Sistine Madonna” has six fingers on his hand?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.