A common story on social media is how French newspapers successively referred to Napoleon during his return from exile as a “monster,” “cannibal,” and “usurper,” and then “His Imperial Majesty.” We decided to check if this is true.

Most often, the story about the behavior of the press during Napoleon's return from the island of Elba is conveyed like this. For ten days, the headlines of the French newspapers changed depending on Bonaparte's advance towards the capital: “The Corsican monster has landed in the Bay of Juan”, “The cannibal goes to Grasse”, “The usurper has entered Grenoble”, “Bonaparte has occupied Lyon”, “Napoleon is approaching Fontainebleau”, “His Imperial Majesty is expected today in his faithful Paris.” This episode is mentioned, for example, in the Russian version “Wikipedia» with reference to the book “Napoleon” by academician Evgeniy Tarle. This story can also be found in historical publications - for example, on the website of the magazine "Amateur», however, without mentioning the source. She is often remembered on social networks, usually as an example of the political volatility of the press. This story can also be found in LiveJournal, and in "VKontakte", and on entertainment sites Pikabu, anekdot.ru And yaplakal.com.

Academician Tarle, the main Soviet-era specialist on the history of the Napoleonic wars, actually cites this fragment in his book Napoleon, published in 1936. Tarle looks like this:

“The government and the Parisian press close to the ruling spheres moved from extreme self-confidence to complete loss of spirit and undisguised fear. Typical of her behavior during these days was the strict sequence of epithets applied to Napoleon as he advanced from south to north. The first news: “The Corsican monster has landed in Juan Bay.” Second news: “The cannibal is coming to Grasse.” Third news: “The usurper has entered Grenoble.” Fourth news: "Bonaparte has occupied Lyon." Fifth news: “Napoleon is approaching Fontainebleau.” Sixth news: “His Imperial Majesty is expected today in his faithful Paris.” This entire literary gamut fit into the same newspapers, with the same editors, for several days.”

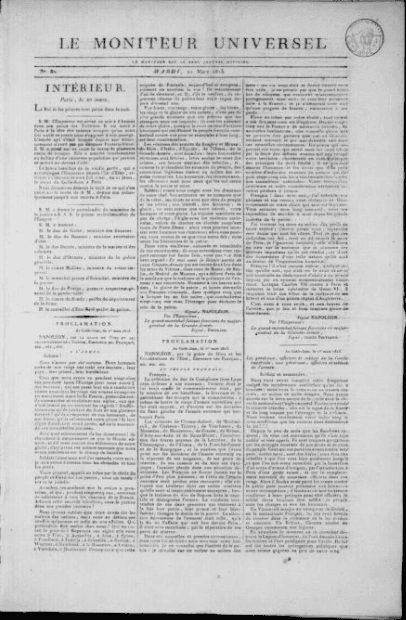

The selection of headlines itself seems dubious: the structure of the newspapers was completely different. If you take a random number of the government's Le Moniteur Universel from this period, you can see that the messages look different.

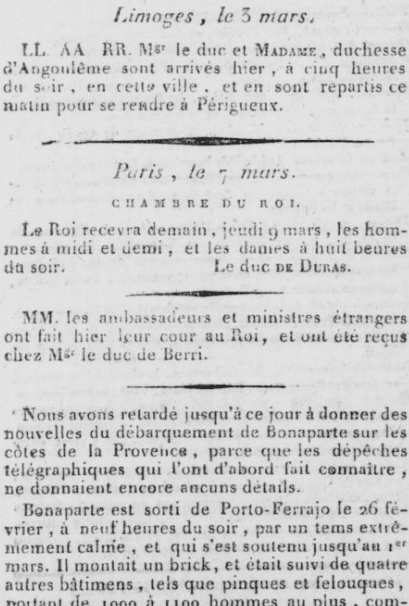

Articles about news from different cities are entitled: “Limoges, March 3” or “Paris, March 7.” Other messages are not provided with headings at all, as in the above excerpt from the March 8, 1815 issue. But we can assume that we are not talking about headlines, but about phrases from various articles.

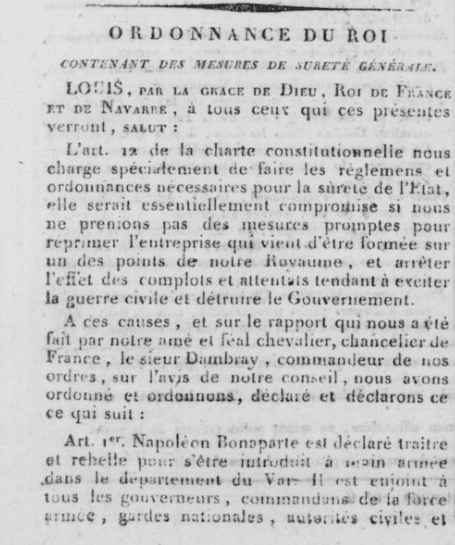

In the official Le Moniteur Universel the first mention of Napoleon's return appears only March 7th. The newspaper published a decree of King Louis XVIII dated March 6, which stated the following: “Napoleon Bonaparte showed himself to be a traitor and a rebel by invading the Var department.” Then the decree talks about the punitive measures that await those who assist Napoleon and his army. There are no evaluative characteristics like “cannibal” or “Corsican monster” there.

The next day, March 8, the editorial office of the newspaper Moniteur apologized readers for the delay in information about Napoleon's landing. “The telegraph dispatches available to us did not contain any details,” writes Moniteur. Further, in a completely neutral informational manner, he describes exactly how Napoleon got to France: on February 26, several ships left Portoferraio, on March 1 they were already in the roadstead of Juan Bay, on the same day Napoleon landed on the shore. The next day Bonaparte's men took the road to Grasse. All roads, according to Moniteur, were controlled by troops loyal to the king, and the routes to retreat were cut off. The first news of the landing, the newspaper emphasizes, reached Paris only on March 5. Again we pay attention to how Napoleon is called: Bonaparte, Napoleon and nothing else - no insults, no ringing definitions.

A little further on the same page of the newspaper for March 8 is an appeal to the king of Parisian municipal councilors. It talks about “a foreigner who stepped onto our shores at a difficult moment for the country”, about the tyranny that existed under Napoleon. But again, no “cannibals”.

New ones appear on March 9 details. The newspaper talks about the desertion of Napoleon's soldiers, about how residents of Grenoble and Marseille hung white royal flags in their windows and shouted “Long live the king!”, about impeccable discipline in government troops. As in the previous issue, the news is followed by an appeal to the king, this time from the Court of Cassation. The landing there is called a “crazy adventure”, and Napoleon himself is called “the enemy of France and the whole world.” But the newspaper only quotes the letter. By that time, Napoleon, without shedding a drop of blood, had already entered Grenoble, and his army had increased several times due to the volunteers who had joined.

The harshest statement in the first ten days after Napoleon's landing belonged to Marshal Soult, in the past one of the emperor's closest associates, and in 1815 - Minister of War under Louis XVIII. Moniteur published his appeal to the army, in which the minister writes that Napoleon “so despises us that he considers us capable of betraying our legitimate ruler.” But there is nothing about monsters and cannibals here either.

In subsequent issues, Moniteur continues to convey news of Napoleon's progress, talk about the universal support of the king and publish letters of loyalty from various institutions. In the issue of March 11, the word “usurper” finally appears - in letter judges of the Seine department.

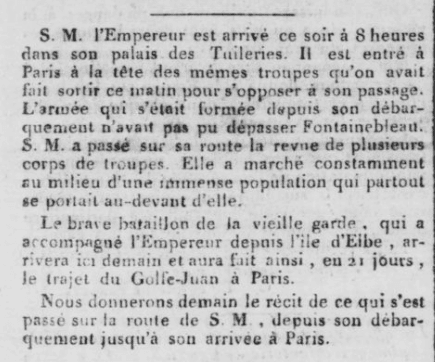

This continues until March 21. Number for this day is remarkable. It begins with a short news of the departure of the king and princes. And then the following article was published: “Paris, March 20. His Imperial Majesty arrived this evening at 8 o'clock at his palace in the Tuileries. The same troops that were sent to stop him entered Paris with him.” At the end of the column, the newspaper promises to publish the next day a detailed account of what happened over the past 20 days, from the landing at Juan Bay to the triumphal procession through Paris.

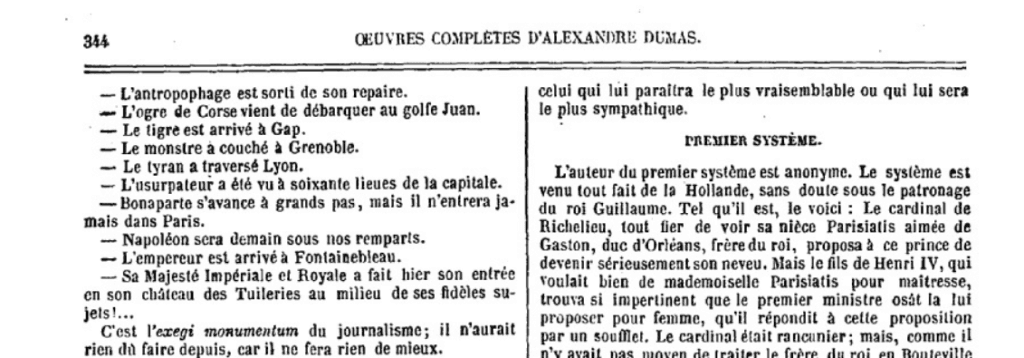

Thus, the main Parisian newspaper for March 1815 does not contain the epithets that Academician Tarle writes about. It remains to be seen where this striking but implausible fragment came from. In 1953, journalist Jacques Kaiser published article in the Monde newspaper, in which he suggested that the widely circulated myth was nothing more than a figment of Tarle’s own imagination. In France, another version was more popular, more complete, published in 1945 in “History of the Parisian Press” by René Mazedieu. In addition to the six titles known from Tarla, there were three more: “The cannibal left his lair,” “The tiger arrived in Gap,” and “The usurper was seen 60 leagues from the capital.”

In 1954 it appeared new article Kaiser, in which he made adjustments to his previous theory. He discovered that the titles appeared much earlier, and their supposed author was none other than Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. In the book “A Year in Florence” (1841) Dumas tells about Napoleon's return from Elba. “To follow Napoleon’s triumphal march all the way to Paris, we now only need to read the Moniteur,” writes Dumas. And then he cites the very “news” that Tarle later took into his book.

“This is a true monument to journalism; after that, you can no longer write anything, you won’t achieve more,” Dumas notes sarcastically.

But Dumas, as it turns out, was not the first to bring “news” about Napoleon’s advance. Most likely, the writer borrowed them from the collection “19th century jokes", published in 1821. Among the many stories, there is one that tells about censorship in 1815. And there are listed those same “news”, and again with reference to Moniteur.

Thus, in real newspapers there is no trace of the story that is often cited to this day in blogs and historical works. Initially, it is a fiction, a historical anecdote, grotesquely describing the rapid change in the political position of the newspaper, which in reality in this case behaved relatively neutrally.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons

Not true

- Is it true that Napoleon was short?

- Did Napoleon say: “A people who do not want to feed their army will soon feed someone else’s”?

- Is it true that the nose of the Great Sphinx was broken off by order of Napoleon?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.