In many sources you can read that sports skates with runners tightly attached to shoes owe their appearance to the Russian monarch. We checked whether this is actually true.

According to the magazine's website, "Around the world", "from the 14th century until the end of the 17th century, skates were made of wood with metal runners and attached to the sole of the shoe with ropes and belts. <…> For the first time, skates with runners tightly attached to the sole were “made” by the Russian Tsar Peter I, who was in Holland on ship business and became interested in ice skating.”

A similar statement can be seen on such resources as “RIA Novosti", "Sport-expreWithWith", championat.com, Sports.ru, "Belarus today", "Interactive Sports Museum", sites libraries, trading network "Sportmaster", in the magazine "Bonfire", as well as in the books "People who changed the world" And "Amazing Russia. 500 facts about our country that will amaze you" "Gazeta.ru“claims that the invention of the Russian monarch is even recorded in the speed skating encyclopedia, which was published in the Netherlands in 1848.

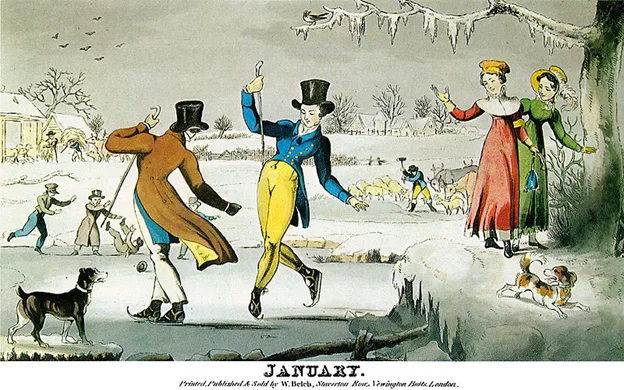

Indeed, as you know, in 1697–1698, Russian Tsar Peter I was part of a delegation Grand Embassy visited Europe, where he got acquainted with factories and factories, shipyards and arsenals, studied shipbuilding in Amsterdam and even received a patent as a shipwright. The Russian delegation also paid attention to traditional Dutch entertainment. Jan Cornelius Nomen in his notes noted: “The Muscovites... took advantage of the winter time and diligently learned to skate on ice, and they repeatedly fell and were seriously hurt. And since they, through carelessness, sometimes skated on thin ice, some of them fell into the water up to their necks. Meanwhile, they tolerated the cold well and therefore were in no hurry to put on a dry dress, but continued to ride for some time in a wet one; then they changed into dry clothes and went for a ride again. They did this so zealously that they made progress, and some of them could skate perfectly.”

Another question is, did Peter really introduce skating to his homeland, as some sites claim? This is wrong. Also, the English ambassador Howard Carlyle, appointed in 1663, noted, that “Muscovites, like the Dutch, have skates, which are used in winter, when the waters are covered with ice... however, not for travel, but only for exercise and warming up on the ice.” Skates, according to Carlisle, among the Muscovites were “made of wood, with a long and narrow iron at the bottom, well polished, but curved in front, so that the iron could cut the ice better.” From another quote (“the high-born are disdainful, but the common people are carried away”) we can conclude that many years later Peter I popularized skates among the Russian nobility. However, as the author of an article in the magazine would write two centuries later,Hercules", "with the death of Peter the Great, speed skating disappeared in Russia." The fashion for skating will return to Russia only at the beginning of the 19th century.

So, we come to the main issue - the design of skates. Some scientists count down The history of this product dates back to at least 1800 BC. e. — around that time, according to their research, the oldest skates preserved to date were made from animal bones in Scandinavia. Their other colleagues They say about even earlier dates. At each end of such a skate there was a hole through which a leather strap was threaded to attach to the legs.

Photo: Federico Formenti

By the 14th century in Europe (particularly in Holland), bone skates were supplanted wooden, with a metal blade at the end.

As is easy to see, such skates were also attached to the shoes with laces, and did not form a single structure with them. Over the following centuries, the shape of the runners was greatly changed: they became taller, a curl familiar to many appeared in front.

But we are still interested in when the boot began to be tightly attached to the metal part of the skate. Oddly enough, according to modern researchers, this happened much later than the era of Peter I. Here, for example, is the reconstruction of skates from the end of the 18th century.

We see that they still use straps. In 1772, the Englishman Robert Jones in his “Treatise on Skating” spoke for screwing the blades directly to the shoe, but this proposal remained on paper. In 1848, avid Pennsylvania skater Edward Bushnell patented Philadelphia Club Skate all-metal skates. But even they had leather straps, and boots were not included. A step forward was to replace the wooden stand with a metal one and the appearance of a special fastening pin for connection with shoes.

And only in 1865 Jackson Haynes developed a two-plate all-metal blade that was attached directly to the boots of a figure skater or speed skater. The production of factory skates with a pre-attached boot was still a long way off. The question arises: if more progressive (essentially modern) skates appeared in Russia at the end of the 17th century, why did they: a) not reach us in the form of museum exhibits; b) did not spread throughout Russia and Europe?

Modern Dutch experts on the history of skating will help answer this question. In the encyclopedia they compiled, a separate page is dedicated to a variety called Peterschaatsen (“Peter’s skates”). It is noted that it appeared around 1650, long before the visit and even before the birth of the Russian sovereign, and remained popular for almost three centuries. The peculiarity of this design was a small heel on the heel of the skates (a copper plate at the back of the stand) and some semblance of a sock in front.

Photo: www.schaatshistorie.nl

This design allowed the foot to stand more stable on the skate, but separate shoes and straps that attached them were still used. Nevertheless, this variety cannot be called particularly popular or considered an intermediate link between ancient skates and current species.

As for the connection with Peter the Great, the Dutch suggest that the tsar became interested in this specific model during his stay in Zaandam, which caused a stir among local residents. Since then, the variety has been nicknamed in honor of the high-ranking guest, although today the word Peterschaatsen is almost forgotten. It is also noted that the Encyclopédie Roret of 1853 includes the term le cothurne russe (“Russian cothurne”) - a high shoe attached to the wooden part of the skate.

Thus, Peter I did not invent skates of the modern type, and the Dutch variety associated with his name appeared even before his birth.

Cover photo: publicdomainpictures.net

Not true

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.