There is a widespread version on blogs and in the media that the ancient expression “About the dead is either good or nothing” is a later abbreviation of the full quote: “About the dead it is either good or nothing but the truth.” We decided to check if this is true.

A version of the existing continuation of the ancient phrase appears every time a famous person dies. For example, State Duma deputy Mikhail Delyagin titled his post exactly this way. LiveJournal about Mikhail Gorbachev: “It’s either good about the dead or nothing but the truth.” In 2017, official representative of the Russian Foreign Ministry Maria Zakharova wrote, that the expression originally sounded exactly like this. Text about the “full version” of the saying on “Zen” dialed 372,000 views. Also, a quote in the form of “nothing but the truth” is often found in thematic collections: on the sites “Year of Literature" And "Cultural studies", V "Komsomolskaya Pravda", in publics in "VKontakte» and on the website citaty.net.

In all cases, the quote is attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Chilo (6th century BC), one of the “seven wise men” of the pre-Socratic era. In turn, the main source of Chilon’s sayings is Diogenes Laertius (II–III centuries), author of the essay “On the Life, Teachings and Sayings of Famous Philosophers.” One of the chapters of his book is dedicated to Chilo. Among the wise sayings of the philosopher Diogenes Laertius cites the following: “Do not blaspheme the dead.” This is, in any case, how Chilon’s statement was translated by Mikhail Gasparov in the academic publication Diogenes Laertius.

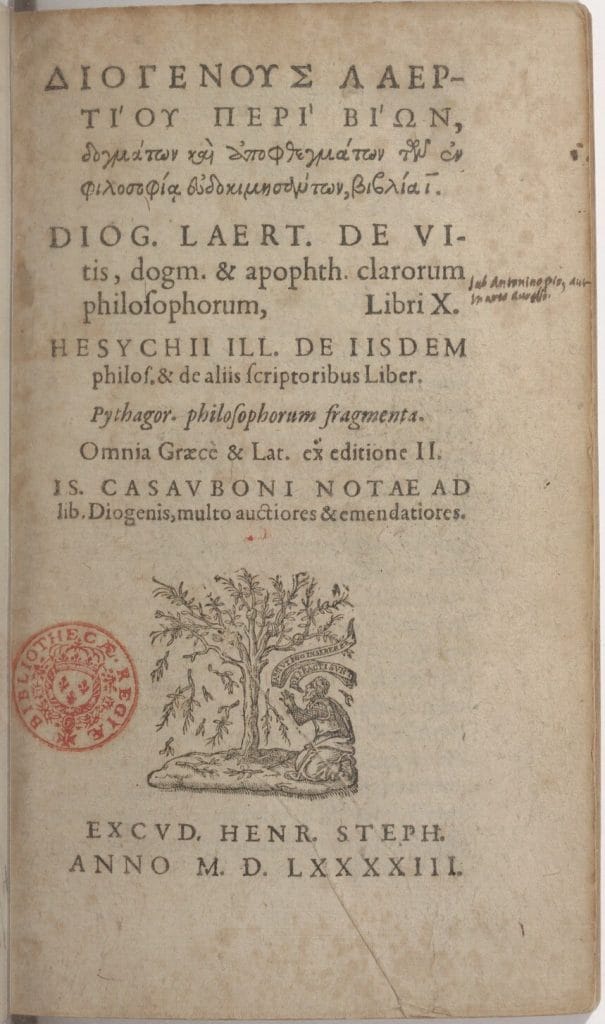

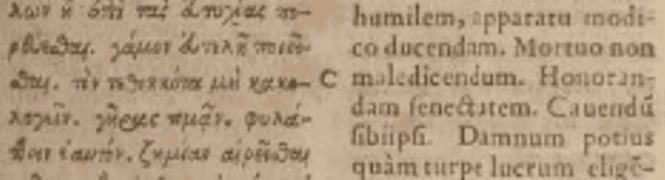

But in order to understand whether part of the phrase has disappeared in translation, let us turn to the Greek and Latin text of the book of Diogenes Laertius. In the 1593 edition given Greek original with parallel translation.

The phrase "Tὸν τεθνηκóτα μὴ κακολογεῖν" is translated into Latin by Isaac Casaubon as "Mortuo non maledicendum".

In both cases, we can conclude that the Russian translation is completely consistent with the original - the phrase can be translated as “Do not speak ill of the dead”, “Do not speak ill of the dead”, but the meaning will not change in any case. Moreover, almost the same statement meets and in Plutarch’s “Comparative Lives,” in the chapter dedicated to Solon, another of the seven sages of antiquity: “They also praise Solon’s law, which prohibits speaking ill of the dead. And indeed, piety requires considering the dead sacred, justice - not touching those who no longer exist, civil moderation - not being at enmity forever.” This is further confirmation that no important words were lost in the original expression.

Over time, the phrase began to appear in several versions, the most popular of which are “De mortuis nihil nisi bonum” (“About the dead, nothing but good” and “De mortuis aut bene, aut nihil” (“About the dead, either good or nothing”). Both versions can be found in Russian literature of the 19th century. The expression appears in Ivan Lazhechnikov’s novel “The Last Novik” (1833), in memoirs Thaddeus Bulgarin (1846–1849), in Afanasy Fet’s story “Uncle and Cousin” (1855).

There is also a variant of the catchphrase with the addition of “nothing but the truth.” But every time this is presented as an argument on the topic of an ancient aphorism. Thus, literature researcher Ilya Simanovsky, studied this question, quotes from published in 1874 notes Prince Odoevsky, who proposed changing the expression: “We are told so often, and we ourselves repeat: “De mortuis aut bene, aut nihil,” that we are ashamed to ask: is there any meaning in this phrase? “None of us seems to have thought that if this phrase were true, then the whole story would have to consist of panegyrics.” And then Odoevsky points out that it would be reasonable to say “De mortius seu veritas, seu nihil” - “About the dead, either the truth or nothing.” Here it is worth paying attention to the fact that Odoevsky does not question the authenticity of the original phrase.

This philosophical polemic exists, for example, in Chekhov’s play “Fatherlessness"(1878). The landowner Glagoliev interrupts the accusatory speech of the village teacher Platonov: “De mortuis aut bene, aut nihil, Mikhail Vasilyevich!” He replies: “No... This is a Latin heresy. In my opinion: de omnibus aut nihil, aut veritas (“about everything or nothing, or the truth.” — Ed.).” And in Alexei Apukhtin’s story “Between Life and Death” (1892), one of the characters tries to remember the phrase: “De mortis, de mortibus...” To which the interlocutor replies: “Do you want to say: “De mortuis aut bene, aut nihil”? But this proverb is absurd, I will correct it somewhat; I say: de mortuis aut bene, aut male (“it’s either good or bad about the dead.” — Ed.).”

In the twentieth century, the phrase is often found in journalism. One of the leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, Viktor Chernov, for memories about Georgy Gapon, he chose the epigraph “De mortuis nihil, nisi verum” - “About the dead nothing but the truth.” It is obvious that here Chernov is also polemicizing with the Latin expression - he exposes Gapon and explains why he was killed. In 1910 in article Lenin was indignant about the death of the former Chairman of the State Duma Sergei Muromtsev with a Latin quote: “The Pharisees of the bourgeoisie love the saying: de mortuis aut bene aut nihil (either remain silent about the dead or speak good). The proletariat needs the truth about both living political figures and dead ones.”

All the examples given show that “nothing but the truth” is an option proposed by various authors to correct the ancient expression. At the same time, none of them doubts that the ancient aphorism clearly did not approve of the censure of the dead.

Until the 2000s "National Corpus of the Russian Language” does not fix the form with the addition of “nothing but the truth” as the true version of the saying. This allows us to conclude that confusion (or deliberate distortion) occurred in our time. Thus, it is safe to say that the quote was not shortened. On the contrary, “nothing but the truth” is a later addition.

Cover image: Paul Delaroche, "Cromwell at the Tomb of Charles I." Wikimedia Commons

Not true

Read on topic:

- Did Dante talk about the hottest places in hell for those who observe neutrality?

- Is it true that Voltaire is the author of the phrase “I do not share your beliefs, but I am ready to die for your right to express them”?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.