On many forums, people write that these two exams showed how developed the candidate’s cognitive abilities were, and that the rest of the subjects could supposedly be memorized. We checked what the exam for future officials of Ancient China actually included.

The ancient Chinese example of two exams in calligraphy and versification is heard in many lectures And interview neurolinguist Tatiana Chernigovskaya. “Why teach a child to write? Not typing on the computer, but writing? In ancient China, people who aspired to become high government officials had to pass two exams. And this was not knowledge of laws at all, but calligraphy and versification. A wise civilization, because they understood that this is a different type of consciousness, a different type of skills,” said Tatyana Chernigovskaya in one of her lectures, which was viewed by about 7.8 million YouTube users. Since then, this statement has been quoted by many forums, articles, quotation books And posts on social networks.

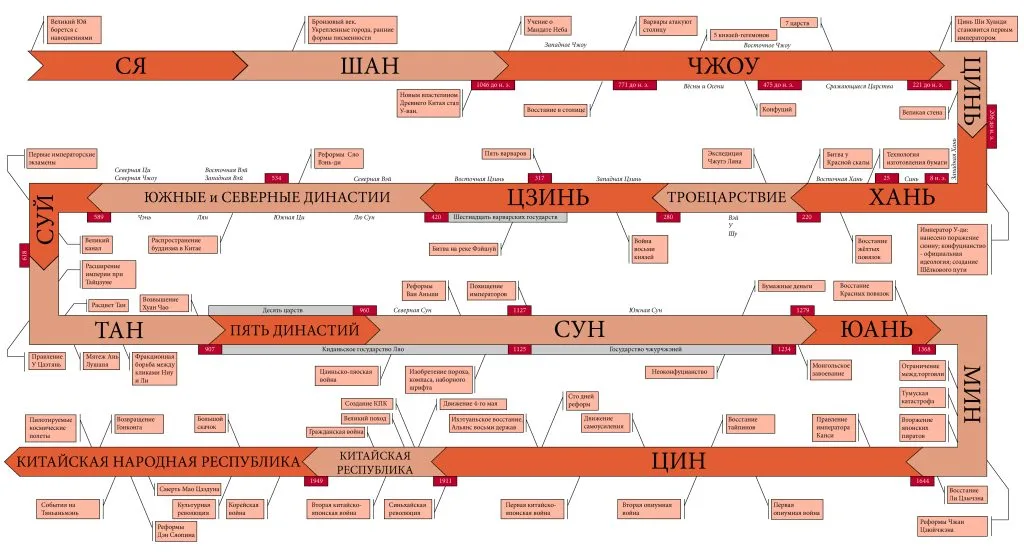

IN interview Chernigovskaya explained to Vladimir Pozner that the system of two exams existed in “one of the many Ancient Chinas, there were different Chinas.” Apparently, this refers to the division of Chinese history into periods of different dynasties. History of Ancient China covers pre-imperial and part of imperial China: from the 16th century BC. e. before 221 BC e.

Centralized states existed before, but the formation of a stable state apparatus of the empire started around the 3rd century BC. e., at Qin Dynasty. In those days, the legitimation of the ruler was based on the concept of the “heavenly mandate” - relatively speaking, the “chosenness” or “benevolence” of higher powers, expressed in the grace and harmony of “de” descending on the population and the state. Emperor took all personnel decisions, formed the management apparatus, assigned titles and ranks to officials. One of the earliest systems affecting the status and advancement of a person was the system "six arts", which existed under Zhou in the 12th-3rd centuries BC. Although calligraphy was one of these arts, there were no examinations in this system. Then, during the Han Dynasty, a system of selection and appointment for civil service was born - "inspection system". Selection methods were mainly limited to the promotion of talent at the local level and the recommendation of worthy candidates for civil service. From each administrative unit, two people with “brilliant talent and filial piety"(one of the central concepts in Confucian philosophy). This is how the main method of selecting officials in Ancient China was formed.

In 220 AD e., in the era Three Kingdoms, in one of the kingdoms a new standard was introduced - Nine rank system. Censors were installed in all regions and districts, who assessed citizens according to several criteria: from virtuous behavior and academic abilities to the number of good deeds done for the province. Depending on merit, the censors assigned worthy candidates one of nine ranks: officials directly subordinate to the emperor had the first rank, and, for example, local judges were assigned the ninth. The disadvantage of this system was that the censors mainly focused on noble family background, and in the end only rich and powerful people became candidates.

None of these systems for selecting officials in ancient China had a place for examinations. The post of official could only be obtained through a recommendation from the censor or by inheritance.

Several centuries later, already during the period of imperial China, the recommendatory selection system began to be gradually replaced by the system of imperial examinations Keju. But even there, the selection of candidates for positions in the government apparatus was much more difficult than testing abilities in calligraphy and versification. Keju examinations were divided into three levels. The first level took place annually in each county, the second - once every three years in the provincial centers, the third - once every three years in the capital, in the imperial residence. On first level candidates took exams on knowledge of Confucian classics, geography, history, the foundations of jurisprudence, government, oratory and other subjects. At the second level, they wrote an essay on knowledge of the Confucian canon and the fundamentals of government. Those who passed both tests received a chance to take the palace exam. It was held every three years at the imperial residence, where the emperor himself asked the candidates a single question, requiring an answer in the form of an extended essay. Good results in an exam at any level gave the right to an bureaucratic post. But the height and status of this post depended on the level of the exam passed.

It is worth noting that around the second half of the Tang dynasty (618–907), the palace examination placed emphasis on the candidate's ability in belles-lettres: poetry, Chinese rhymed prose, and eulogies. The remaining stages of the exam, as expected, included a test of knowledge of Confucian classics, jurisprudence, government, etc. The skill of calligraphy was also assessed during each exam. After the change of the Tang dynasty, the palace exam took on the same format: one question about the political structure of the empire, for which an extended essay had to be written as an answer.

Since the time of keju examinations, education in imperial China was limited to preparation for examinations. Public and private schools at all levels have turned into institutions where they engage in habitual cramming. After including a regulated eight-part composition education became even more standardized. In the 1900s they began to sound opinions, that the main obstacle to the dissemination of new knowledge “was none other than the keju examination system.” Finally, in 1905 Qing court abolished the imperial examination system, which had existed for more than a thousand years.

So, the assertion that in Ancient China candidates for the post of official were tested only on their abilities in calligraphy and versification has practically no basis. Calligraphy was indeed assessed in all written stages, but there was no separate exam. For several hundred years, versification was indeed part of the last stage in the palace. But before reaching this stage, candidates had to prove themselves in a host of other disciplines, such as mathematics, political science, memorization of canonical works, etc. We turned to Tatyana Chernigovskaya for an explanation of which period of Ancient or Imperial China she had in mind in her lecture. She promised us to look for her source, but at the time of publication she did not give an answer.

Image: The Emperor receives candidates during a palace examination. Source: WikiCommons

Mostly not true

Read on the topic:

- World History Encyclopedia: The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China

- Unmistaken identity: a guide to the rank badges of ancient China

- Chinese Embassy: History of China

- Theory&Practice: Disinterested bureaucrats: how officials were selected and trained in imperial China

- Is it true that tutoring has been banned in China?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.