There is information on the Internet about the image of Tsar Ivan IV on a Baltic cannon. We decided to check how true this statement is.

Publications with headlines like “The only lifetime sculptural image of Ivan the Terrible on a propaganda cannon from Revel” are, for example, on Pikabu and in LiveJournal. Posts where this information is given with the clarifications “allegedly” or “alleged” are in publics on VKontakte and on the website "Science and Technology". As an illustration, the portrait of Ivan the Terrible on a cannon also found its way into printed publications. In particular, it is in Leonid Katsva’s textbook "History of Russia" (2005), books "John IV the Terrible" Gleb Blagoveshchensky (2010), "Tsar Ivan the Terrible" Leonty Lannik (2008), “The Capture of Kazan and Other Wars of Ivan the Terrible” by Valery Shambarov (2014), “Essays on the History of the Livonian War” by Vitaly Pensky (2017) and others, in some cases with a question mark, sometimes without. Penskoy, for example, writes: “A probable lifetime portrait of Ivan the Terrible.”

We are talking about a really existing item - the “Revel Lion” squeak, created by master Carsten Middeldorp from Lubeck in 1559 for Livonia, which at that time was at war with Russia. This arquebus became a military trophy of the victors and is now stored in the St. Petersburg Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps. The date of manufacture of the cannon and the name of its creator are known from the German inscription on it:

He called me Leo

Revel magistrate,

So that his enemies

I would destroy

Those who do not want to live in peace with him.

Karsten cast me in 1559

Middeldorp is true.

The torel (back wall) of the barrel is decorated with a shoulder-length image of a man, in whom some recognize the king.

Historian of Russian artillery Alexey Lobin in his book “The Artillery of Ivan the Terrible” tells, how the theory about this identification arose. The compiler of the first guidebook of the Artillery Museum, Nikolai Brandenburg, pointed out at the end of the 19th century that, most likely, this is a self-portrait of the foundry worker Carsten Middeldorp, with which there was Agree researcher Leida Anting (1967). But archaeologist Kirill Shmelev in 2002 presented version that, most likely, the master depicted Tsar Ivan the Terrible. She mentioned and in the 2004 museum reference book, edited by Valery Krylov. This version picked up researcher Sergei Bogatyrev, who presented detailed evidence in a 2010 article and more concisely in publications 2011. Lobin himself in 2013 wrote on his blog: “My version is more cautious. The “head of a Muscovite” is depicted here - it is somewhat premature to talk about sculptural similarity with the appearance of Ivan the Terrible.”

Despite the fact that about 20 years have passed since the emergence of this theory, no other art critic or historian, except these researchers of military affairs, doesn't discuss “The Lion of Revel” as a possible image of Ivan the Terrible (not counting one article with objections to Bogatyrev, which will be discussed below).

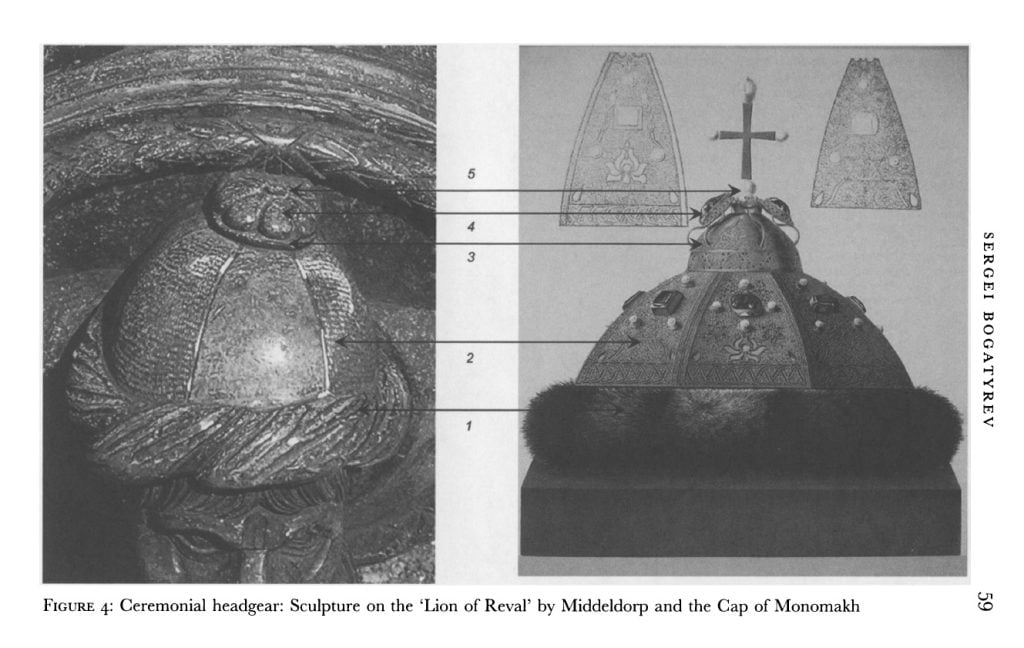

What arguments do Shmelev and Bogatyrev give when identifying the head on the cannon with the king? Shmelev writeswhat the headdress looks like Monomakh's cap, and around the neck one can see barmas (a wide precious mantle): “The depiction is of a man of Eastern European appearance, wearing a hat with a fur roll-like edge. It is precisely these hats that are typical for depictions of Muscovites in European engravings of the 16th–17th centuries. <…> The hat has parameters quite close to the Monomakh cap - the headdress of Russian tsars; around the neck there are details reminiscent of barmas. Finally, the face of the person depicted bears a significant resemblance to the familiar image of Tsar Ivan IV. The appearance of Grozny is known from several Western European engravings and a portrait from the National Museum in Copenhagen.”

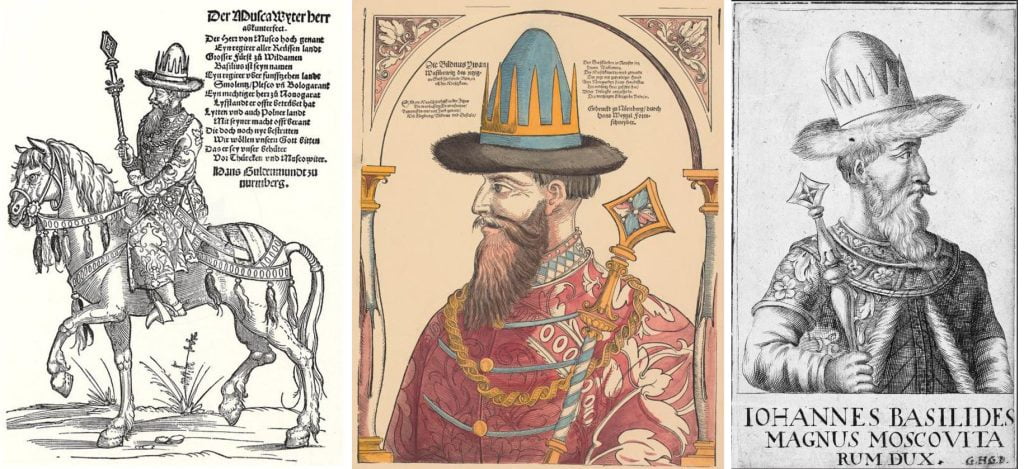

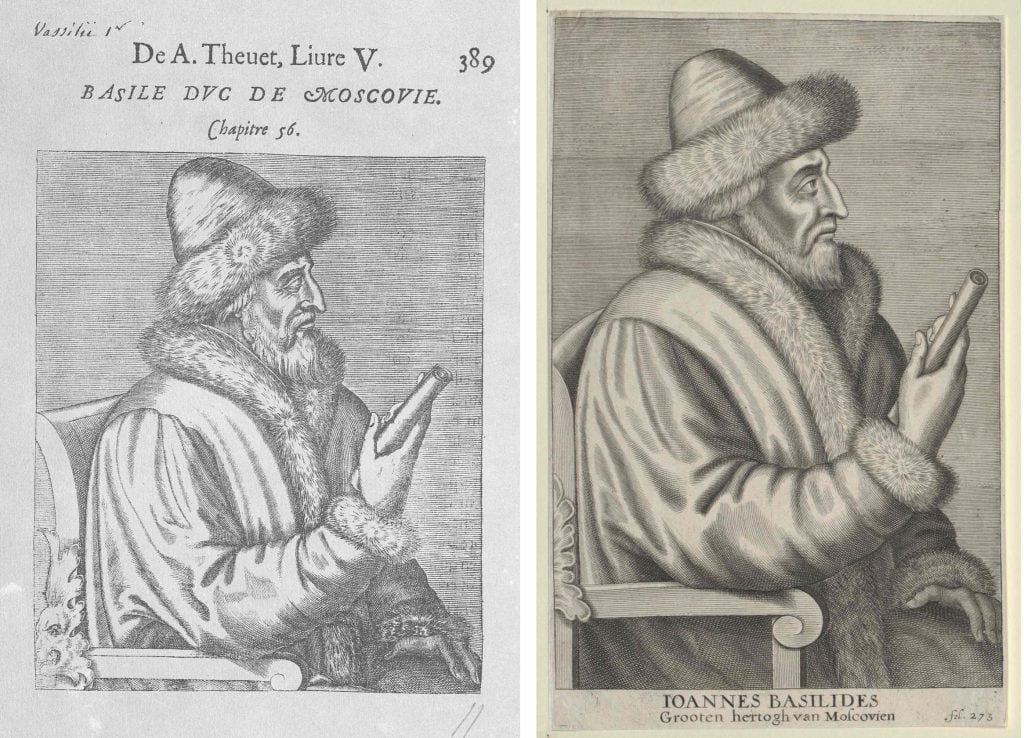

Bogatyrev develops this version. He begins by describing the vast Western European tradition of creating exotic fictional portraits of Moscow sovereigns, which began in the first half of the 16th century with the engravers Erhard Schön and Augustin Hirschvogel with their depictions of Ivan the Terrible's father, Grand Duke Vasily III. It is known that European creators of engraved portraits of Ivan IV used portraits of his father - the most famous of them is the woodcut by Hans Weigel the Elder (1563) with the image of Ivan IV, based, as Bogatyrev points out, on the portrait of Vasily III by Schön. Bogatyrev writes that the foundry worker Middeldorp also used Schön’s engraving, borrowing from it the curled mustache and pattern on the collar. “But how Middeldorp differs from Schön is the amazing historical authenticity of the ceremonial headdress,” writes Bogatyrev. — N. E. Brandenburg misinterpreted the hat in the image of Middeldorp as an oriental turban. In fact, this is a very early and in many aspects unique image of Monomakh’s cap.” Next, Bogatyrev compares the image of this real regalia and the man’s hat from the cannon. He also believes that the collar pattern on the latter is the royal barma, another important regalia of Russian rulers.

Thus, three groups of arguments can be distinguished: firstly, the cannon was made by contemporaries and neighbors of Ivan the Terrible, secondly, there is a physiognomic similarity, and thirdly, the attributes are read as “Russian”.

The fact that the gun was manufactured in a neighboring state can indeed serve as an argument that its customers had a special interest in the person of Ivan or in general in the “Muscovites”.

Now let's move on to the issue of physiognomic similarity, which “catches the eye” and instantly convinces non-professionals. Bogatyrev, by the way, does not insist on the similarity of the portrait. “Of course, it is tempting to view this as a realistic portrait of Ivan the Terrible,” he writes, but since there is nothing to compare with, the researcher considers this image symbolic, imaginary, but truly indisputable.

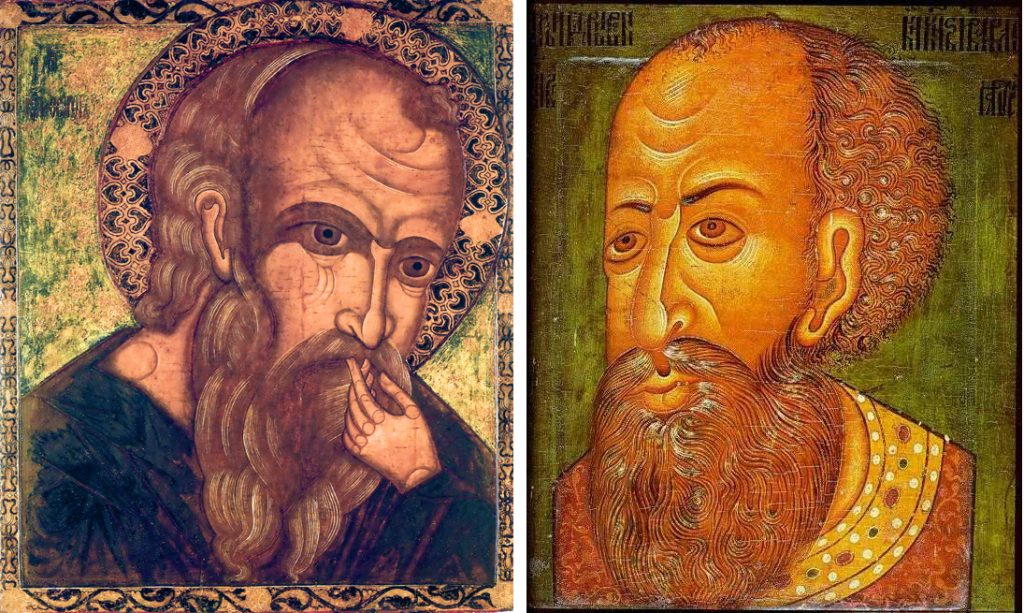

Indeed, there is almost no material for comparison. Our idea of Ivan the Terrible's appearance is largely shaped by popular culture. The most plausible portrait, it would seem, can be called the Parsuna from the Copenhagen Museum - was consideredthat it belongs to the group of tombstones, as well as the portrait of Ivan’s son, Fyodor Ioannovich, and commander Skopin-Shuisky. On the paper sticker on the back there is a Latin inscription stating that the parsuna was a gift from the king Fedor Alekseevich to the Danish ambassador Friedrich von Gabel in 1677. However, in 2004, this famous monument finally arrived at a temporary exhibition in Russia, at the Historical Museum, where it fell into the hands of our specialists. They examined it under a microscope and are surethat the painting, judging by its composition and technique, was certainly created in modern times, at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, and by an artist who did not have professional icon painting skills. A possible prototype has even been found - icon “John the Theologian in Silence” (1560s) from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery.

Right: “Parsuna of Ivan the Terrible” (National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen)

Ivan the Terrible never posed for portraits in the modern sense of the word (made from life and as similar as possible), since a similar genre in Rus' was just beginning to take shape - in the above-mentioned tombstone icons and parsuns. True, European artists made images of Russian rulers - not from life, but from the words of travelers, after a while. “Imagine: a person attended an embassy reception in a palace, which was attended by the tsar. Let's say that after a year he returned to his country and told the artist what the ruler looked like. And the master, as he understood, painted, taking other people’s impressions as a basis. Of course, there can be no talk of reliability here, much less scientific physiognomic value,” tells historian Elena Ukhanova, who is looking for a barely noticeable portrait of Ivan on the binding of the first printed "Apostle".

Such conditionally lifetime Western European portraits from the time of the main Russian connoisseur of engravings Dmitry Rovinsky Only two engravings are considered: a woodcut by Hans Weigel the Elder (1563) and a profile portrait dependent on it (that is, made on its basis with changes to the author’s taste) from the book of Paul Auderbon (1585). Weigel's source, Maybe, was inspired by the above-mentioned portrait of Vasily III by Schön. By another version, Weigel made the engraved portrait earlier, and the attribution of the image of Vasily III to Schön is erroneous, it is later.

In the center: G. Weigel-sr. Ivan IV (1563)

Right: P. Auderbon. Ivan IV (1585)

Several engraved portraits of Ivan - just copies portraits of Vasily with a new inscription. That is, having no idea about the appearance of their son, the artists did not hesitate to use the fictitious image of their father (an idea of the real appearance of Vasily III is given by his gravestone icon). Engravings with imaginary portraits of Ivan were the only things Middeldorp could see. Bogatyrev’s assumption that the foundry worker could go to Moscow and see the Tsar and Monomakh’s hat up close with his own eyes seems an incredible stretch.

Right: Portrait of Ivan IV

Thus, all that remains is a sculptural reconstruction of the skull, completed Academician Mikhail Gerasimov. It looks like an image from a parsuna - perhaps because the academician used this visual source as inspiration, unaware of its falsity. And also because the icon “John in Silence” follows the ancient patterns of painting images that developed in Byzantium, and Ivan the Terrible, through the female line, was a descendant of natives of this particular region, which reflected in the bone structure of his skull. Surely the academician also looked at the tombstone icon of Vasily III. Gerasimov's reconstruction is the closest depiction of Ivan the Terrible's appearance that we have. However, it should be borne in mind that today it cannot be considered as ironclad proof: modern scientists question some of the conclusions of the Soviet anthropologist and believe that sometimes his artistic decisions were influenced not by bones, but by theories. For example, disputed reconstruction of the appearance of Andrei Bogolyubsky, to whom Gerasimov gave pronounced Mongoloid features.

A funny moment, if we appeal to this method of evidence: the head of the “Revel Lion” has much greater similarities with another reconstruction of Academician Gerasimov - the prince Yaroslav the Wise (XI century), however, in this case it is obvious that we are just talking about a coincidence.

In the center: fragment of the Revel Lion cannon

Right: portrait of Ivan the Terrible (reconstruction using Gerasimov’s method)

Now a little art historical analysis. The facial features of the person on the Revel Lion are distinctive and may seem unique. However, from the point of view of an art critic, they are very typical. The author, German foundry maker Carsten Middeldorp, may have been good at casting bells and cannons, but as a sculptor he was by no means a virtuoso. His weakness as a portrait painter, for example, is evidenced by the excessively forward lower part of his face - this is a common anatomical mistake in bad sculptors. Despite the fact that Middeldorp worked in the middle of the 16th century, at the height of the Renaissance, the works of this provincial German master demonstrate the features of a rather naive stylization characteristic of Gothic art. The same manner of stylizing thin faces can be found, for example, in the earlier statues of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Finally, the third group of arguments is the image of Monomakh’s cap and barm. Bogatyrev writes: “We can only guess where Middeldorp could have obtained such detailed information about the real appearance of Monomakh’s cap. One possible source could be his Revel customers. He could also have learned about it from other German foundry workers who visited Muscovy. Being often trained engineers and draftsmen, they could give a professional description of what Monomakh's hat looked like." Further, the researcher makes a very bold conclusion: “Based on the portrait of Middeldorp, we can confidently conclude that in the middle of the 16th century, Monomakh’s cap, in general, had the same appearance as it does today.”

However, a distinctive feature of the Monomakh cap and other hats of the Russian kingdom for centuries was the fur trim - this detail is preserved in the most imaginative European engravings. It seems strange that “trained engineers and draftsmen” could miss such an important nuance when describing the royal cap. The “Revel Lion” undoubtedly does not have fur: the frame of the headdress is depicted using lines imitating thin folds of fabric folded and twisted around its axis. You can see how imitation fur is depicted in metal above, in the reconstruction of Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

Separate article dedicated criticizing Bogatyrev's ideas about Russian royal hats, the historian Yulia Igina, who considers the “Revel Lion” to be simply a sculptural image of a barbarian of a semi-Tatar appearance, as the Muscovites were represented in Europe. “The hat depicted in the portrait resembles Monomakh’s hat in the sense that the crowns of both consist of four sectors connected by a pommel. At the same time, the Cap is hemispherical, and the hat in the portrait is ovoid. The headgear and pommel of both differ.” She also emphasizes the absence of sables: “However, the most important thing is that the hat in the portrait is wrapped around the band with a turban, which denies the interpretation of this image as Monomakh’s hat.”

Images of Turks in turbans were also widespread in European art of the Renaissance, and they were much more popular than images of Tatars and Muscovites. The interaction between Europe and the Ottoman Empire was very active at that time, so Turks often appeared in European art. One of the peaks of fashion for such images connected with the period after 1529, when the Ottomans besieged Vienna.

The division of the headdress into sectors is also found in eastern headdresses.

Maria Kullanda, an expert on Ottoman art and an employee of the State Museum of Oriental Art, shared her assessment with us. In her opinion, “the hat (from the “Lion of Revel” - Ed.) does not resemble a specific Turkish headdress of this time, including the decoration on top. However, stylization is always possible - for example, on a Russian cannon of the 17th century called “New Persian” (1685, master Martyan Osipov) there is also a human figure depicted on a vingrad (protruding part - Ed.), and a headdress there is of a turban type, but rather conventionally Persian. But the existence of this “New Persian” indicates the tradition of placing an “eastern” figure on the cannons, given that this is a Russian master and of a later time).” Also in the Kremlin there is an earlier captured bronze Persian cannon, cast in 1619 by master Mikhail Rotenberger in Poland and confirming the existence of a similar tradition among German-speaking foundries.

In addition, it is important that Western European masters of that period were not at all interested in the Monomakh cap and barmas as separate regalia, and never made separate sketches or detailed images of them. They had no idea how important hats and barmas were for the Russian kingdom, and therefore captured only the general exotic appearance. The sudden interest of the provincial foundry worker Middeldorp in the most realistic (as Bogatyrev believes) reproduction of the appearance of Monomakh’s cap seems inexplicable and implausible.

So how sums up in his article Igina: “The attempt to see in this portrait a reliable image of Ivan the Terrible in the Monomakh’s hat is, in my opinion, devoid of any basis. First of all, it is difficult to identify the old man presented in the portrait with the real Ivan the Terrible, who, as A.N. Lobin noted, was 29 years old at the time the gun was made. <…> In any case, if we assume that the formidable Moscow Tsar is depicted on the gun, then we are dealing not with a reliable, but with an imaginary appearance.”

Middeldorp could not personally see Ivan the Terrible, nor could he see his images made from life, since such did not exist in principle. He actually had the opportunity to use engravings depicting certain Muscovites, the rulers Vasily III or Ivan IV. However, in this case, his work is only a symbolic, fictitious depiction of the enemy. However, other elements of the gun’s decoration and the text on it do not support this theory. It is impossible to prove it using any other iconographic analogues.

Cover photo: fotosergs.livejournal.com

Not true

- K. Shmelev. About the image of the “Muscovite” on the Revel cannon of the Livonian War era

- S. Bogatyrev. Bronze Tsars. Ivan the Terrible and Fedor Ivanovich in the Decor of Early Modern Guns

- E. Ukhanova and others. Lifetime portrait of Ivan the Terrible: visualization of an extinct monument using natural scientific methods

- A. Zhabreva. Russian costume in Western European engravings of the 16th century: truth and fiction

- Is it true that Ivan the Terrible killed his son?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.