There is a popular opinion that Ukraine and Georgia cannot become members of the alliance until they resolve disputes with their neighbors, as required by the rules for admission to NATO. We checked how valid this argument is.

In December 2021, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs published drafts of two documents “on security guarantees” and measures to ensure it, which the United States is proposed to sign. In them, in particular, it says about NATO’s obligation to exclude “further expansion of the alliance”, including the possible entry of Ukraine into this military-political bloc. Moreover, Russia requires from NATO "return to the lines" of 1997. A month after the official transfer of the draft documents to the American side, Russia held a series of international negotiations: January 10 in Geneva with the USA, January 12 in Brussels with NATO and January 13 in Vienna with the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

The publication of the draft treaty and agreement, as well as subsequent negotiations, caused active discussion in the media, blogs and social networks. A number of speakers questioned the validity of the demand that Ukraine not be included in NATO membership. They argue that it is redundant, since the alliance, by its own rules, cannot accept into the organization a country embroiled in territorial disputes. Thus, on January 15, 2022, journalist Yulia Latynina appeared on the radio station “Echo of Moscow” stated: “NATO simply has a rule: not to accept those countries that have some kind of acute territorial conflicts. In this sense, Ukraine and Georgia, of course, simply do not make it through this selection process. And if you think about why Putin arranged Donbass and Lugansk, then one of the rational options, to what extent such behavior is rational at all, may be the answer that then Ukraine will definitely not be accepted into NATO with such ulcers on the territory.”

A similar point of view back in December 2021 expressed Ukrainian Ambassador to NATO Natalia Galibarenko, suggesting that “the Russian Federation has already tested this technology in Georgia: it has looked at what elements work, and is working on something similar with minor adjustments in relation to Ukraine.” Earlier about the impossibility of Ukraine joining the alliance without resolving territorial disputes spoke, for example, Estonian President Kersti Kaljulaid. Similar statements appeared in the materials of major news agencies, including “RIA Novosti" And TASS.

The North Atlantic Alliance (NATO) emerged in 1949, when 12 countries signed North Atlantic Treaty in Washington. The United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Italy and Portugal have made a number of commitments to “protect the freedom, common heritage and civilization of their peoples, based on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.” The signatory countries also declared their “determination to join forces with the goal of creating collective defense and preserving peace and security”—measures to achieve this goal were described in the treaty that laid the foundation for the alliance.

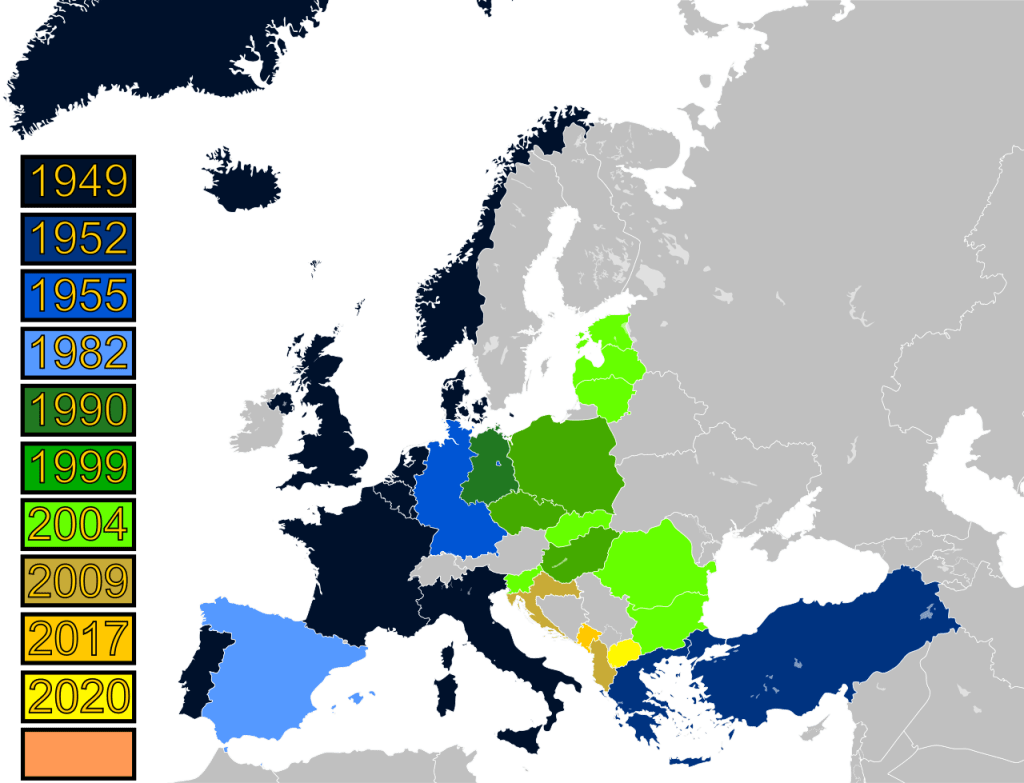

The treaty initially implied the possibility of including new member states in NATO, but not every country could join the alliance. In Article 10 it says: “The contracting parties may, by common consent, invite any other European state capable of developing the principles of this treaty and contributing to the security of the North Atlantic region to accede to this treaty.” Over the next four decades (until 1989), NATO replenished only four new members: Greece and Türkiye joined the organization in 1952, West Germany in 1955, and Spain in 1982. In 1990, a full member of the alliance became already united Germany.

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse Warsaw Pact organizations, which united the socialist states of Eastern Europe and the USSR, NATO gained additional opportunities for expansion. “Some of the new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe were willing to begin integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions,” it says on the alliance website. It is widely believed that the refusal of such expansion was promised to USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev - for three decades this topic has remained the subject of controversy regarding interpretations mostly oral and rather vague agreements.

Be that as it may, the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s became turning points not only for the USSR, its allies and satellites, but also for NATO. At the November 1991 summit, participating states accepted The Rome Declaration, which spoke of “a new chapter in the history of the alliance.” NATO members welcomed “the commitment of the Soviet Union and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe to political and economic reform following the abandonment of their peoples from totalitarian communist rule” and expressed their readiness to help any steps in this direction, because their “own security is inextricably linked with the security of all other states of Europe.” The declaration further describes in detail the already launched and proposed for future implementation of multilateral partnership initiatives between NATO countries and former socialist states in a variety of areas. At the same time, the text does not say anything explicitly about the possibility of their joining the alliance.

Already at the beginning of 1994, at the summit in Brussels, NATO's position became more specific. In the declaration adopted at the end of the meeting was confirmed “commitment to strengthening security and stability throughout Europe” and the desire to “strengthen ties with democratic states in the east (of Europe - editor’s note).” The authors of the declaration also emphasized that the alliance remains “open to the membership of other European states capable of promoting the principles of the treaty and contributing to the security of the North Atlantic region”: “We expect and welcome the expansion of NATO to include the democracies to our east, as part of an evolutionary process, taking into account political and security developments throughout Europe.”

In the same declaration, NATO countries launched the initiative "Partnership for Peace". This program involves bilateral interaction between the alliance and non-alliance countries to maintain security in Europe. In 1994–1995, agreements on participation in the program signed virtually all non-NATO European countries and former Soviet republics in Asia. Russia also became a participant in the initiative quite quickly, in June 1994, and remains in this status to this day.

The next year the alliance published The NATO Enlargement Study outlined the principles and goals of the process, analyzed its possible positive and negative consequences, and, most importantly, presented the criteria that a country must meet in order to receive a formal invitation to join the alliance. Special attention was paid to relations with Russia and their development against the background of the process of future expansion. However, the text does not say which countries and when will be able to join the alliance.

The idea that countries that have territorial disputes with other states cannot join NATO until they are resolved appears to have originated with this 1995 study. Its sixth paragraph states: “States with ethnic or external territorial disputes, irredentist claims or internal jurisdictional disputes are obliged to resolve them peacefully and in accordance with OSCE principles. The resolution of such disputes may be a factor in the decision to invite a state into the alliance.”

However, already in the next, seventh paragraph of the “Study” it is stated: “There is no fixed, rigid list of criteria for inviting new member states to join the alliance. The decision to expand will be made on a case-by-case basis. <…> The allies will decide by consensus whether to invite a new member to the alliance.” This point is also emphasized in the fifth chapter of the Study (paragraphs 70–72), which lists the “expected” characteristics of an applicant state and its actions that will help realize its desire to join NATO. They mention “commitment to and respect for OSCE norms and principles”, including dispute resolution described in paragraph 6.

In 1999, at the summit in Washington, there was accepted Membership Action Plan (MAP). This document became the basis for formalizing invitations to Central and Eastern European states to join the organization. The plan lists a list of measures proposed to the candidate state, the implementation of which will help the country meet the requirements of the 1949 treaty. Those wishing to join the alliance are also “expected to peacefully resolve” any external and internal territorial disputes by peaceful means in accordance with OSCE principles. In other words, in this document, the complete absence of such conflicts is not indicated as a mandatory condition that must be strictly observed.

© Patrick Neil

In 2016, journalist of the BBC Russian Service Boris Maksimov in his article presented a very extensive selection of territorial disputes that exist among the current members of the alliance - both among themselves and with other states. The vast majority of examples cited by journalists concern countries that joined NATO even before the adoption of documents in the 1990s, according to which such conflicts could become the basis for discussions about membership in the organization. Thus, Maksimov’s text does not make it possible to assess to what extent the criterion of the absence of territorial disputes became truly important for NATO during active expansion.

In order to at least try to give such an assessment, it is worth turning to the experience of the countries that have joined the alliance in recent years. Even before the approval of the MAP, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary received an invitation to become members of the alliance. This procedure is successful ended in 1999. Three years later, through participation in MAP, similar negotiations began with Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. These seven countries also joined the alliance in 2004. In 2009, Albania and Croatia joined the ranks of NATO members, and in 2017, Montenegro. North Macedonia was the last to join the alliance in March 2020.

Several of these countries had various territorial disputes with their neighbors when they joined NATO. Here are some examples:

- Estonia is still didn't make a deal agreement with Russia on the state border, although since the 1990s such attempts have been made several times were undertaken. In 2005, the year after the Baltic republic joined NATO, the treaty was even signed by the foreign ministers of both countries and ratified by the Estonian parliament. However, the Russian side refused to do this, citing unacceptable additions in the text of the preamble. A new version of the treaty was agreed upon and signed in 2014, but none of the countries has yet ratified it due to the consequences of the events in Crimea and the conflict in south-eastern Ukraine;

- Croatia since 1990s argues with Serbia about exactly how the border between the countries runs along the Danube. Countries' positions differ regarding the virtually uninhabited 140 km2, mostly consisting of islands and forests. In the early 2000s there was created a bilateral commission to resolve this issue - its activities, however, have not yet led to any significant results;

- Romania, which joined NATO in 2004, has been argued with Ukraine on the maritime border between the two states. In 1997, the country officially ceded Zmeiny Island in the Black Sea to the former Soviet republic, which became part of the USSR after World War II, but the mineral-rich underwater areas around the island remained the subject of debate. In 2004, after unsuccessful negotiations on the division of territorial waters, the case was transferred to the International Court of Justice, five years later the judges supported the Romanian position.

Such examples show that, in general, NATO indeed “expects” candidate states to resolve territorial disputes, but often does not require completion of this process by the time a positive decision is made by the alliance. We emphasize that such disputes are resolved, as required by MAP, peacefully - through diplomatic negotiations, the creation of joint commissions or filing a claim in international courts. Moreover, the presented discussions about drawing borders arose after the collapse of large states (USSR and Yugoslavia), and not as a result of armed clashes.

Possible entry into the alliance between Ukraine and Georgia in this sense is fundamentally different from the situations described above. Both countries, like other post-Soviet republics, back in 1994 joined to the Partnership for Peace, and in the mid-2000s received from NATO an invitation to “intensive dialogue.” This format of communication between the alliance and the state wishing to join it implies the provision of comprehensive support for reforms that will help the candidate country meet the requirements of the organization. At the same time, the “intensive dialogue” itself does not impose any formal obligations for the country’s further mandatory admission to NATO and is rather symbolic and political in nature.

So far, neither Ukraine nor Georgia have even been offered to join the MAP, which has now become a mandatory condition for candidate countries. It is possible that one of the reasons for a significant slowdown in this process was military conflicts on the territory of the two countries: 2008 war in the case of Georgia and military-political processes, which began in 2014, in the case of Ukraine. Although efforts to peacefully resolve these conflicts are being undertaken at least in relation to Ukraine, the threat of their solution by military means does not disappear completely - this distinguishes the situations with the two post-Soviet republics from the examples described above. In such a situation, the inclusion of a country in NATO may automatically make the alliance a participant in an armed conflict that occurred without its direct participation. The nature of such disputes is also important - we are not talking about a riverbed or a small island, but about territories where many people live.

It is difficult to say unambiguously how significant a role serious territorial disputes with Russia play in the issue of (non)admission of Ukraine and Georgia into NATO at the present time. On the one hand, the head of the alliance representative office in Kyiv, Alexander Vinnikov, in August 2021 statedthat the conflict in Donbass will not prevent Ukraine from becoming a member of the alliance. On the other hand, Vinnikov then emphasized that the emergence of a new member of the organization should always strengthen NATO’s security. It is likely that this goal will be more difficult to achieve if, at the same time as expansion, the alliance begins to participate in the conflict.

As it were, both countries participate in exercises that NATO conducts together with its external partners (note that in 2011, even before the Ukrainian crisis, the Russian Air Force also accepted participation in practicing joint operations with alliance forces), and the Georgian military was even involved in operations in Afghanistan.

As for the prospects for the two countries to join the alliance, the formal, legal process has not yet been launched. January 12, 2022, when NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg directly asked about such a possibility for Ukraine, he did not give any clear answer: “Members of the alliance are ready to support Ukraine on the path to membership, helping to carry out reforms and modernize the armed forces so that they meet NATO standards. And then, at the end of the day, it's up to NATO allies and Ukraine to decide on membership." Stoltenberg has a similar position expressed three months earlier, emphasizing that the possible entry of Ukraine and Georgia into the alliance "obviously will not happen tomorrow" and that both countries must do much in the future to achieve full membership in the alliance. At the same time, on January 14, 2022, the secretary general of the organization in an interview with the Italian newspaper La Repubblica stated, that the “decision” on the future accession of Ukraine and Georgia to NATO was made back in 2008, but it is unknown when this will happen.

Thus, the mere presence of territorial disputes in a country applying to join NATO is not considered an insurmountable obstacle when considering the relevant application. Alliance documents and established practice show that the nature of such conflicts and especially the measures to resolve them are much more important. A state wishing to join a union is obliged not only to solve existing problems peacefully, but also to ensure that the likelihood of using force in this process is almost zero. This position is understandable - otherwise, if the conflict moves into a more acute phase, NATO may become a participant in hostilities, and the declared main goal of the organization and its expansion is, on the contrary, to strengthen the security of member countries.

It should also be remembered that current NATO members approve an application for expansion of the organization based on numerous factors and on an individual basis. Therefore, the weight of some of them, such as reforming the army or commitment to democratic institutions, may be significantly higher than some others - for example, the presence of a territorial dispute of varying degrees of seriousness. Whether or not to take such territorial disagreements into account is no less a political than a legal question, which is appropriately recorded in the documents of the alliance.

Half-truth

- NATO. The North Atlantic Treaty

- NATO. Partnership for Peace program

- NATO. Study on NATO Enlargement

- B. Maksimov (BBC Russian Service). NATO countries have many territorial disputes

- Is it true that the United States promised Gorbachev not to expand NATO to the east?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.