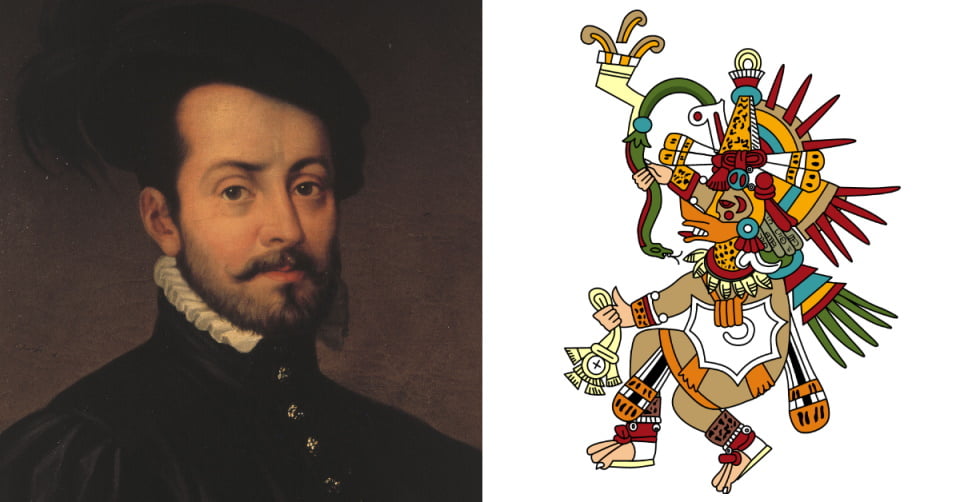

According to the popular view, what helped the Spaniards conquer the last great empire of Mesoamerica was that the Aztecs mistook their commander for a god. We checked how convincing the evidence for this legend is.

This is what the encyclopedia says "Myths of the Peoples of the World" about one of the main deities of the peoples of Central America: “According to one of the Aztec myths, Quetzalcoatl... retired on a raft of snakes to the eastern overseas country of Tlilan-Tlapallan, promising to return from overseas after some time. Therefore, when the bearded Spanish conquerors landed on the east coast of Mexico in the year dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, the Aztecs initially mistook the Spanish leader Cortez for the returned Quetzalcoatl.”

This information is widely reflected in culture, from fiction to history textbooks. So, it is mentioned as a fact in the textbook "Culture of the Ancient World", books "Travelers and Discoverers", "Commanders and Conquerors", "100 Great Cities of the World", on sites "Culturology", "Gazeta.ru" and in many other sources. It is often claimed that Montezuma, the Aztec emperor, himself made a similar mistake.

As you know, in 1519, a detachment led by conquistador Hernan Cortes landed on the Gulf Coast, who later succeeded conquer territory of the Aztec Empire, having captured the local ruler Motecusoma II, to whom, at the instigation of the Spaniards, the not entirely correct name of Montezuma was assigned.

The first evidence that allows us to trace the roots of the legend we are considering is contained in the second letter Hernan Cortes to Charles V (October 30, 1520). However, first we will present some popular assessments this document.

The American historian Warren warns his colleagues against relying on Cortez's letters: "When using them, every researcher must remember that they represent the work of a man who sets out his own version of events in order to make a favorable impression on the Spanish king." The authors are also critical "The Cambridge History of Latin America" (Volume I): "The so-called transfer of the empire to Charles V by Montezuma, as described by Cortes in the artfully woven network of fiction and fact with which he regales the Spanish Emperor in his famous letters, marks the beginning, and not the end, of the conquest of Mexico." The letters were given mixed assessments in Soviet historiography. “The “reports” of E. Cortes,” notes V.V. Zemskov, “are the most important source about the conquest of Mexico, at the same time, some studies in recent years have cast doubt on many episodes of the conquest as presented by its leader. This circumstance clearly reveals the artistic and documentary nature of Cortez’s letters, where only individual historical facts received a very subjective, distorted interpretation, but virtually the entire version of events turned out to be deliberately corrected.”

Now, actually, about the letter. According to Cortez, Motecusoma, a few days after his capture, summoned all the rulers of the nearby cities and declared: “I believe you know from your ancestors that we are not the original inhabitants of this land, and that they came here from a very distant country, and they were brought by the ruler (senior) who left us here and whose vassals we were all... And he said that someday he will return or send someone with such force that will force us to obey him authorities. You know well that we have always expected this, and judging by what this captain (Cortez - author's note) told us about the ruler and lord who sent him here, and judging by the side of the world where he came from, but in his words, I am sure that this is the ruler we were expecting."

Thus, Cortes, with all the artistic component of the letter, does not write that he or his companions were mistaken for gods. In his words, Montezuma called the Spanish king the ruler. What kind of ruler, if we are talking about gods? The answer to this question is below.

Let's take a closer look at Quetzalcoatl, or rather, Quetzalcoatl, since the Aztecs had two of them. The first - translated as “feathered serpent” - was one of the main deities pantheon of Central American Indians with the body of a snake and the bright plumage of a quetzal bird. Quetzalcoatl occupied an important place in the mythology of Teotihuacan, and later became the supreme god of the Toltecs, Aztecs and Mayans (the latter revered him under the name Kukulcan). The second, known as Topiltsin, was most likely a real person. This was the name of one of the Toltec rulers of Tula (Tollan), who lived in the 10th century. According to legend, as a result of a fierce struggle for the throne with rivals from another group of nobles and priests, Topiltsin was defeated and was forced to flee with his followers to the southeast, to the Gulf Coast. Topiltzin was the high priest of the god Quetzalcoatl, with which their future identification and the semi-legendary status of the ruler are connected.

Hence the conclusion: the legend of Cortes, who was mistaken for a ruler who had once left these lands—albeit semi-legendary, but still not quite a god—would be more consistent with the logic of facts. Let's say Montezuma really mistook Cortes for the god Quetzalcoatl. However, by the time of his abdication, the emperor had to be convinced of his own mistake many times (the defeat of the temple of Quetzalcoatl in Cholula, the murder of three sages - experts in the cult of Quetzalcoatl in Coyoacan, his own captivity) and renounce his previous faith.

Most likely, Cortes did not know the myths about Quetzalcoatl. Neither he himself nor the conquistador and chronicler Bernal Diaz del Castillo ever mention the name of this god in their works. If we compare Cortes with the ruler Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl, then a big problem arises: none of the sources says that he was the last ruler of Tula, his dynasty ruled for several more centuries. And then a completely different people came here - the Aztecs. Therefore, it is strange to consider the enlightened Motekusomu a complete ignoramus and fool who decided to transfer power to the envoys of the Toltec ruler who died 600 years ago.

It is important to note that in none of the Indian documents and legends, nor in any code of pre-Columbian times, is there any mention of the fact that Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl would return to the country from the east and again receive supreme power in it. Nowhere, except for the later Spanish chronicles, is there evidence that the god Quetzalcoatl had blond hair, white skin, a long beard and tall stature. He was usually depicted with a black beard and a painted face, or even with a bird's beak.

In addition, we note that after the so-called Nights of sadness, when Cortez fled from Tenochtitlan, having lost all his artillery, gunpowder and two-thirds of his soldiers, the Aztecs had a chance to start all over again, even if they had initially had some “divine” legend in their heads. Such a myth could not help the final conquest of Mexico. But after its completion, it became a convenient tool for justifying the cruelties of the Spanish conquerors and accelerating the Christianization of the Indians.

For example, the Spanish Franciscan monk Bernardino de Sahagún moved to the New World only in 1529, ten years after the events described, and his "Florentine Codex", which describes Motecusoma’s admiration for the “divine” Cortes, was generally created in the second half of the 16th century. The fact is that the conversion of the Aztecs to Christianity was incredibly difficult - they considered the Europeans to be strangers imposing their religion. Then the Franciscans decided to connect the conquest of Mexico with divine predestination. They studied the events that preceded the arrival of the Spaniards and interpreted them as omens and signs of the coming conquest. Another author who popularized the myth of the Spanish gods is the Spanish historian Francisco Lopez de Gomara, who himself had never been to the New World, but decades later became the secretary of Cortes who returned to Spain. The attitude of modern historians towards his works is also extremely skeptical.

Finally, one of the main sources of information about the gods in the guise of the Spanish conquistadors is the chronicles of the aforementioned Bernal Diaz "The True History of the Conquest of New Spain". In them, recounting how Cortes persuaded the Totonacs (a native people) to imprison an Aztec tax collector, the author describes the response of the Indians: “The act they witnessed was so amazing and important to them that they said that no man dared to do such a thing, and it must be the work of the teules. Therefore, from that moment on, they began to call us teules, which means “gods” or “demons.”

Diaz also has other quotes related to the Spanish conclusion of an alliance with the state of Tlaxcala, one of the main enemies of the Aztecs.

1. “... speeches were heard that we were genuine teules (deities) and that we should be appeased with gifts.”

2. “Peace with Tlaxcala increased our glory enormously. Earlier they saw us as teules, that’s what they called their idols, but now everyone finally bowed down with fear before the victors of the proud and strong Tlaxcala.”

There are a few problems with these episodes, however. Firstly, it is not very clear whether the Spaniards themselves popularized the use of the word teule in relation to themselves, or in each individual case it was the initiative of local residents. Secondly, the languages of these peoples do not contain the word teule. Another local Nahuatl language has the word teōtl, not found in Totonac. It was interpreted by the Spanish as "gods" or "demons". However, the Mesoamerican teōtl is not an analogue of the Greek or Roman gods, but rather simply a supernatural being. Let us note that when the Spaniards arrived in the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, Montezuma, in a conversation with Cortes, put an end to this, and in narration Bernal Diaz, he emphasizes that he himself was called a god: “I know very well, Malinche, what nonsense the Tlaxcalans, your faithful allies, told you: that I am like a deity or teul and that in my houses everything is gold, silver and precious stones; they know well that this is not so, but they, not believing it themselves, wanted to deceive; now, Señor Malinche, you see, my body is made of bones and flesh, like yours, and my houses and palaces are made of stone, wood and lime; I will say, sir, I am a great king, it is true, having the wealth inherited from my ancestors, this is not nonsense and lies that they told about me, comparable to the lie that I own your thunder and lightning.”

Anastasia Kalyuta, senior researcher at the St. Petersburg Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, believes The most accurate translation of the word teōtl is the concept of “spirit”. She notes that the above-mentioned Spanish sources mention rich Aztec gifts to Cortes and his associates, including elegant paraphernalia of a number of gods. At the same time, as she writes, such honors were common practice in relation to foreign leaders, even enemy ones. In addition, she does not exclude the possibility that foreigners were thus prepared for the sacrifice, which, according to traditions, could take place either in a month or in a year. Kalyuta also, in principle, admits the option of deification as theoretically possible, but there is no strict evidence in favor of this version. Again, we should not forget that the chronicles of the Franciscan monks, which mention the fact of donating costumes, are, on the one hand, recognized unreliable, and on the other hand, they could just become the basis for the legend about the divine perception of the conquistadors among the Aztecs.

Thus, the information that the conquistador Hernan Cortez was mistaken for the god Quetzalcoatl is not an entirely accurate interpretation of the legend about his identification with the ruler Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl. The latter, in turn, is based on the myth mentioned by purely Spanish historians that the latter must return to the heart of Mexico. Finally, the word teōtl, which may have been used to refer to the conquistadors, does not have a single meaning of “god,” and the Spanish conquerors themselves could have popularized its use in their regard.

Most likely not true

Read on topic:

1. Indians of Mexico and European conquest: traditional stereotypes and reality

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.