Recently, you can often come across stories about an ideological incident that occurred in Soviet times with one of the most authoritative dictionaries of the Russian language. We checked how plausible it is.

This is what it tells us Maria Averina Literary Club: “In the second edition of Ozhegov’s dictionary (1952), the word “Leningrader” appeared, although there were no names of residents of other cities. They ordered it to be inserted there to separate the words “lazy” and “Leninist” from each other.”

You can also learn about this story from the editor-in-chief of the Gramota.ru website Vladimir Pakhomov, leading researcher at the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Alexander Vasilevich, leading researcher at the Institute. Pushkin Alexandra Olkhovskaya, on the online learning portal "House of Knowledge", V “The most necessary book for the most necessary place”, on the website Bryansk Museum of Local Lore and in many other sources.

The names of residents of populated areas (in the particular case of cities - for example, “Leningrader”) are called katoikonyms in linguistics. How note specialists, catoikonyms are indeed rarely found in explanatory dictionaries, since these words require “not interpretation, but simple correlation with a specific toponym, they require encyclopedic reference, which contradicts the principles of compiling explanatory dictionaries.”

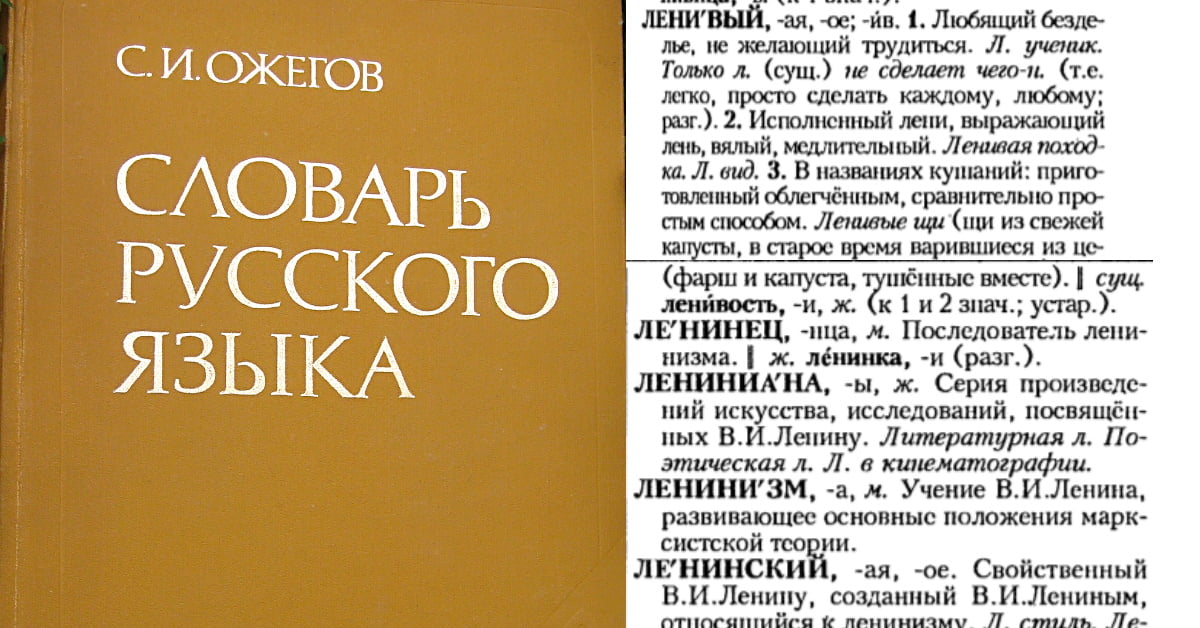

Now about dictionaries. In 1935–1940, a four-volume book was published in the USSR "Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language" edited by Professor Dmitry Ushakov. In parallel, in 1939–1940, work began on a one-volume dictionary, the editors of which were also headed by Dmitry Ushakov. However, in 1942, the professor died in evacuation in Tashkent, and his closest assistant Sergei Ozhegov took on the main work of compiling the dictionary. "Dictionary of the Russian language" was first published in 1949, went through five more lifetime editions (in 1952, 1953, 1960, 1963, 1964) and is still being published (after Ozhegov’s death, work on the dictionary was continued by his student Natalia Shvedova).

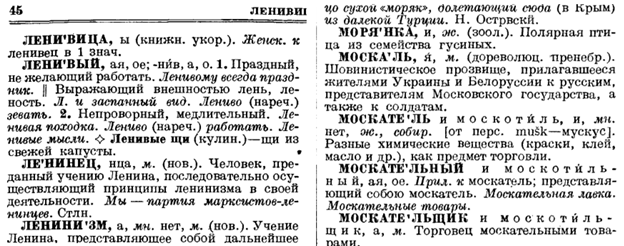

Let's first look at Ushakov's dictionary. His second volume (L - Oyalovet), published in 1938, does not contain either the article “Leningrader” or, for example, the article “Muscovite”. “Lazy” here calmly coexists with “Leninist”:

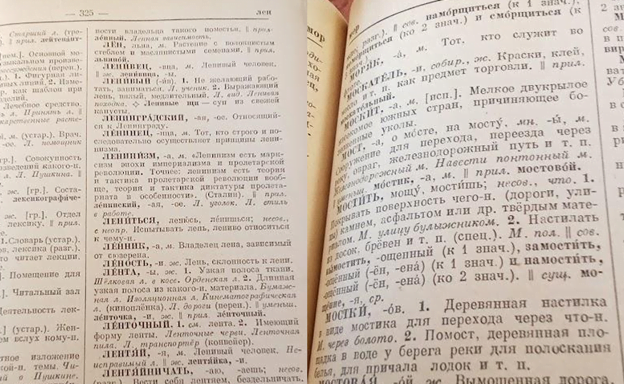

Now let’s turn to the first edition of Ozhegov’s dictionary (1949):

As we can see, between the above articles a new article actually appeared - however, not about the word “Leningrader”, but about the word “Leningradsky”, which has the same root as it. At the same time, the situation with “Moscow” has not changed. Note that this happened already in the first edition of Ozhegov’s one-volume dictionary, and not in the second, as numerous sources claim.

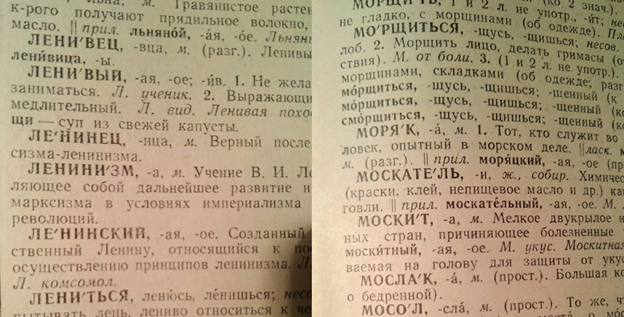

But in the 1970 edition there are no such articles:

Moreover, they are not in the 17-volume "Dictionary of modern Russian literary language" edited by Vasily Chernyshev, although his volume “L-M” was published much earlier - in 1957. That is, several years after the incident with Ozhegov’s dictionary, high-ranking officials apparently considered the seditious proximity acceptable. However, given the volume of articles in the 17-volume volume and their arrangement on different pages, it does not seem realistic to read “the lazy Leninist” at once.

In the publication "Domestic lexicographers of the 18th–20th centuries" (2000) provides the following episode from the biography of Professor Ushakov: “When reading the proofs of the second volume of the dictionary, the political editor discovered that after the word “lazy” in alphabetical order comes the word “Leninist”, and then “Leninism”, “Leninka” (feminine correspondence to the word “Leninist”), “Leninist”... The censor saw here almost ideological sabotage, an insult to the name of the great leader. He demanded that the blasphemous juxtaposition of the adjective “lazy” and “Leninist” words be eliminated, for which it was necessary to insert some neutral word between them. But to do this, it was necessary to invent a word that does not exist in the Russian language, or, for example, to include the word “Leningrader” in the dictionary, thereby violating the principle according to which the names of residents are not described in this explanatory dictionary. Ushakov remained firm and did not change anything in this part of the dictionary, although at that time such firmness could have cost him, if not his head, then his freedom.”

Around the same time, for the 100th anniversary of Sergei Ozhegov, a collection was published “Dictionary and culture of Russian speech”, which included the memoirs of the famous linguist. In one of the episodes of the book he admits:

“Why do you think the word “Leningrader” is in my dictionary? After all, the names of city residents are not given in it..

It turns out that the censorship was not satisfied with the fact that the word “Leninist” followed immediately after the word “lazy” (it would turn out to be “lazy Leninist”!). It was necessary to insert something between them ... "

And although in this part of the memoirs we seem to be talking about Ozhegov’s work on Ushakov’s dictionary (in particular, it is said just below that the book was completed before the start of the war), the absence of the words “Leningrader” or “Leningradsky” in the four-volume book, as well as the mention of “my dictionary” may mean that Ozhegov had mixed memories and he was actually talking about his own one-volume book. There are also a few more curiosities with different words.

From all of the above, we can conclude that the order to somehow scatter the words “lazy” and “Leninist” was given back in the 30s, when compiling Ushakov’s dictionary, but the latter insisted on his own, but Ozhegov in the next decade already had to submit to the demands of censorship. However, the dictionary did not last long in this form. And although the details of the story contain inaccuracies (part of speech, year of publication), it cannot be called fiction.

Most likely true

Read on the topic:

1. The legend about the “Leningrader” - truth or fiction?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.