In September 2021, the Reims Gospel arrived in Moscow for an exhibition in the Kremlin. The manuscript is surrounded by numerous legends. We figured out how true they are.

The average version of the legend goes like this. The daughter of the Kyiv prince Yaroslav the Wise, Anna Yaroslavna, married Henry I of France in 1051. In her dowry, she brought from Kyiv a most valuable manuscript in Cyrillic. During her coronation, Anna Yaroslavna showed persistence — refused to swear in the Latin Bible and took an oath in the “native” Gospel. The first king to swear on it during his coronation in the Cathedral of Reims was Philip I, the son of Anna, in 1059. Until 1793, all French monarchs swore allegiance to this Orthodox Gospel. At the same time, the French could not read the incomprehensible letters for centuries, so the manuscript was called the “book of angels.” And only Peter I, during his visit, began to read Russian fluently right from the page, revealing the secret of the origin of the book.

In particular, some people write about this travel websites, portal "Russian trace in world history", website "Military Review", Ukrainian news agency UNIAN and other sources. The legend is also mentioned in books, including "Yaroslav the Wise" Vladimir Duhopelnikov, "Wives and Maidens of Ancient Rus'" Tatiana Muravyova, "Relics and Treasures of the French Kings" Sergei Nechaev and many others.

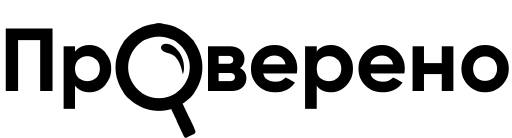

Let's start with the fact that, formally, Princess Anna Yaroslavna in the 11th century could not physically bring the manuscript “The Reims Gospel”, which is stored today in the Municipal Library of the city of Reims (France), since now this book consists of from two bound manuscripts in Cyrillic and Glagolitic, created in different centuries. Its second, larger Glagolitic part dates back to 1395, written in the Croatian version of Church Slavonic. The inscription in it, in addition to the date, reports that it was created in Prague, in the monastery of St. Jerome, after Emperor Charles IV donated the first part to the monastery. It is believed that it was then that both parts were combined under one cover, forming the “Reims Gospel”.

But what about the first, Cyrillic part? Could Anna Yaroslavna bring her to France? No direct instructions in text there is no manuscript for the date and circumstances of creation. However, analysis of the text, font and ornaments shows that this manuscript was actually created in the middle of the 11th century. It is written in the Old Russian version of the Church Slavonic language. Modern scholars of writing thinkthat it was indeed created in Kievan Rus, probably in the scriptorium of Yaroslav the Wise, deceased in 1054.

Thus, this manuscript could actually have been completed in Kyiv before Anna Yaroslavna left for France (near 1051), and she could take it with her. But is there any documentary evidence for this? Not a single one: there are no lists of her dowry, and there is no detailed description of her marriage. The manuscript does not appear in any historical documents for a long time. The Cyrillic half of the Reims Gospel was first mentioned only in 1395, when a scribe in a Prague monastery made an inscription, saying: “As for the other part of this book, it corresponds to the Russian rite. It was written by St.'s own hand. Prokop, abbot, and this Russian text was donated by the late Charles IV, Emperor of the Roman Empire, to immortalize St. Jerome and St. Prokop."

If you believe that Anna Yaroslavna brought the manuscript to Paris in the 11th century, then how did it end up in the 14th century in the Holy Roman Empire, in the hands of its emperor? Unknown. The Empire, especially its Slavic territories, was a fairly close neighbor of Rus', so it is more logical to imagine that the manuscript came to Prague from the east, rather than from the west. Please note that the Czech monk names the author of the Cyrillic text as Prokop, that is, the Czech saint Procopius of Sazavsky (c. 970–1053). This means that no associations with France or Kyiv grew up around the manuscript at that time.

What are other known hard facts about the Reims Gospel? There are many legends and theories, but the following iron fact that's how it is: in 1574, the French Cardinal Charles of Lorraine donated it to the Reims Cathedral, with which its history will be connected in the future. If you believe that the manuscript was already in this cathedral under Anna, then this will be an amazing coincidence. Why did the cardinal give it to Reims? Perhaps he heard about the legend and simply returned the book to its place? No, it's just that since 1538 he served here as an archbishop. Where the manuscript was before this time is unknown.

By the way, the date 1574, although historians believe it, is not so reliable - we only learn about it from inventory 1669. Thus, 274 years lie between two mentions of the manuscript, and Anna Yaroslavna has never appeared in the descriptions. But they arise other legends: they say, it was written by Saint Methodius himself, brought to Reims in the 9th century by Archbishop Ebbon of Reims or the crusader emperor Baldwin, who found the manuscript in Constantinople.

In the 18th century, after the visit of “Russian tourists”, about whom the story will go below, the French already knew that the letters in the first part were not ancient Syriac or Greek. But the legend about the princess had not yet arisen. When, in 1782, Empress Catherine the Great officially requested a certificate of historical rarity from France, answer there is not a word about Princess Anna, although it is obvious that such a story has the right place in the message to the Russian ruler.

The Great French Revolution with its plunder of churches and monasteries is the reason for the next gap in the fate of the Reims Gospel. In 1793, a heavy silver frame with precious stones and sacred relics was stripped from it - the relics of saints and, very importantly, a particle of the Holy Cross. Protocol on this preserved. The book itself disappears from the cathedral, but the old parchment was lucky - someone donated it to the library, where it was identified around 1835. It is then that Anna Yaroslavna finally appears.

Researcher of the princess’s life, historian Alexander Musin counts the story about the Gospel in her dowry is one of the numerous myths and legends that formed around the figure of Anna Yaroslavna, and believes that the composition of this tale occurred no earlier than the 1830s. This date is interesting in that only shortly before this Nikolai Karamzin discussed in relatively detail osvetill the circumstances of Anna Yaroslavna’s marriage in her “History of the Russian State,” making her interested in the fate of educated Russians. In 1836, one of Karamzin’s acquaintances, a prominent cultural figure, Alexander Ivanovich Turgenev publishes in the “Journal of the Ministry of Public Education” a small message entitled “Ancient news about Anna Yaroslavna and the Slavic Gospel in Reims.”

According to Turgenev, “one of our compatriots staying in France” found in Reims “in the spaces between the lines of a church manuscript hitherto unknown information about Anna Yaroslavna.” In addition, he “took out a photograph from the first page of the ancient Slavic Gospel,” written in Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet, on which the kings swore allegiance and which Peter the Great examined. It is clear from the text that we are talking about two different manuscripts: in one, something about the princess is written between the lines, the other is the Gospel. However, these two ringing names, finding themselves in the same headline, very quickly became intertwined.

French researcher Valérie Geronimi, who in 2018 conducted a revision of all the legends about the manuscript, also believes, that one of the impetuses for the creation of the myth was the surge of interest of people at the beginning of the 19th century in the romantic figure of Anna. In particular, in 1805, the St. Petersburg “Severny Vestnik” published the news that Pyotr Dubrovsky acquired “the personal library of Anna of Kyiv” in Paris, but did not show it to anyone.

In 1837, local archivist Louis Paris finally recorded the presence of the Gospel in Reims. He published description of the manuscript and listed a wide variety of hypotheses of its origin, mentioning Anna Yaroslavna’s dowry (however, without reference to the source).

The legend received a second wind at the turn of the century, when acted Franco-Russian alliance. Geronimi draws attention that the manuscript was shown to Nicholas II during his visits to France in 1896 and 1901. In the twentieth century, serious scientists (for example, Lydia Zhukovskaya in her monograph “The Reims Gospel: the history of its study and text”) repeatedly refuted the legend, but this did not prevent the spread of the tale.

The second component of the legend is the use of the "Reims Gospel" during the coronation of all French kings. As we have already seen, it could not be useful to “all kings” due to the date of its arrival in Reims (1574). But what about those monarchs who were crowned after this date? There may be only four: Henry III (1575), Louis XIII (1610), Louis XIV (1654) and Louis XV (1722). Henry IV of Navarre was crowned at Chartres Cathedral (1594), and Louis XVI (1774) certainly did not use the Reims Gospel, like later sovereigns.

Geronimi emphasizes: “Not a single historical document confirms the presence of the “Reims Gospel” during the coronation of the French monarchs” (more precisely, we are talking about the religious rite of coronation). However, historians admit that such a possibility still exists, although the first clarification of which particular Gospel was used is very late. It appeared in 1746 in Abbé Plushet's book Le spectacle de la nature. The Reims Gospel is not mentioned in any historical documents describing the ceremony, although its local name Texte du Sacre (literally “coronation text”) indicates a special status. Nevertheless, since the 18th century it has been widely asserted that the “Reims Gospel” was used in the ritual (in particular, this was reported to Catherine the Great in the letter mentioned above). However, it is strange that not a word was written about this by contemporaries of the coronation of Louis XV in 1722 or historians who described the reign of the Sun King who died shortly before.

Be that as it may, it is known that the kings in Reims swore by placing their hand on a certain Gospel and a cross. If it was the “Reims Gospel” that was used, then most likely think historians, for the reason that a relic was mounted in its frame - a particle of the Life-Giving Cross, and not because of the value of the manuscript itself.

Finally, the third part of the legend is about Emperor Peter the Great, who quickly read the text of the mysterious manuscript “in Russian.” This legend pays tribute to the encyclopedic knowledge of the sovereign, making him a kind of our first paleographer. However, firstly, the Church Slavonic language of the 11th century, of course, differs from Church Slavonic, which the young prince studied at the end of the 17th century. So this text, which causes difficulties even among specialists, was hardly read fluently in Russian.

In the Reims Cathedral, by the way, they themselves did not believe that they had a king, at least in the 18th century. In 1782, the flyleaf of the Gospel was marked postscript: “The royal sub-chancellor, passing through Reims on June 27, 1717, read the first part very fluently, as did the two gentlemen who were with him: they said that the language of the manuscript was their natural language.” The sub-chancellor is Pyotr Pavlovich Shafirov, diplomat, polyglot, former head of the embassy department, who had extensive experience working with a variety of fairly ancient Russian documents. A little later, in 1726, the Gospel examined, after reading the text, Russian Ambassador Boris Kurakin. A description of his visit has been preserved, which indicates the interest of the Reims clergy in exotic tourists in the cathedral sacristy.

Did Peter ever visit Reims? French documents confirmthat in 1717 the king, traveling from Paris to the Netherlands through Livry, Soissons and Aretal, stopped in Reims. However, he spent only a few hours there, after which he left for Liege. The municipality then spent 455 livres and 13 sous on a single dinner. French report, that the king came to Reims to see the famous cellars of the Abbey of Saint-Nicaise, where champagne was made.

Perhaps, after dinner and champagne, Peter also managed to accompany Shafirov to the cathedral, according to his long-standing habit, incognito. However, the myth-making algorithm, in which the sub-chancellor of Peter I, during retellings, turns into Peter I himself, is obvious. This happened in the 19th century - as mentioned above, Alexander Turgenev wrote about this.

Thus, the Reims Gospel represents a remarkable case of a whole bunch of beautiful but completely untrue stories.

Not true

- Museums of the Moscow Kremlin. Exhibition “France and Russia. Ten centuries together"

- "Reims EGospel" on the website of the Municipal Library of Reims

- V. Geronimi. L'évangéliaire slavon de Reims mythes, (re)découverte historique et perspectives

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.