In many sources you can read that pasta owes its appearance in Italy to the famous Venetian traveler, who met it in the Celestial Empire. We checked if this is true.

This is what the website of the center of Italian culture tells us "Bellingua": “Many people think that spaghetti was invented by the Italians. However, this is not entirely true! The Italian traveler Marco Polo brought dry and well-preserved long noodles from China in 1295. In his "Book of Miracles" he describes it as one of the oriental wonders. The Italians liked this dish so much that they immediately began active creative work to invent new types of such noodles. There is no doubt that the huge variety of pasta is an Italian invention, but flour products of this type were known long before Marco Polo among many peoples of Asia and Africa.”

Similar information can be read in publications such as "The Newest Book of Facts", "Culinary Encyclopedia", “KGB correspondent: notes of an intelligence officer and journalist”, magazine "Knowledge is power", and in many other sources.

Pasta is one of the symbols of Italy. Today there are dozens of varieties this culinary product, bearing intricate Italian names, which are very easy for foreigners to confuse - well, how to distinguish cavatappi from cavatelli? However, this does not mean that pasta has always been in Italy. On the other hand, the mention of Marco Polo in such stories can immediately cause mistrust. After all, the Venetian personality semi-legendary, he became the hero of many theories, the authors of which claim that Marco Polo never visited China, and invented his travel stories based on popular legends. However, modern research show, that the Venetian merchant, most likely, honestly stated what he saw himself and what he was told about on his long trips. The question is how true some of the information he heard was. In any case, the story with pasta requires special attention.

It should be noted that Marco Polo himself did not write or publish anything. The Book of Wonders of the World (also known as the Book of the Diversity of the World) about the Venetian's travels to the East in 1276–1295 is based on his stories, which were heard and written down by the writer Rustichello (Rusticiano) of Pisa, Marco Polo's neighbor in the Genoese prison. “Journeys” consists of four parts. The first describes the territories of the Middle East and Central Asia, the second - China and the court of Kublai Khan. The third part talks about coastal countries: Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia and the east coast of Africa. The fourth describes some of the wars between the Mongols and their northern neighbors. But even these retellings have not reached us in their original form - about 150 editions of the epoch-making book are known.

And if you try to find in the Chinese part of the “Book of Wonders of the World” information about products that even slightly resemble pasta, nothing will come of it. But in another book, which describes the Sumatran state of Fansur (now the territory of Indonesia), said: “There is no wheat or other grains here; people eat rice and milk; They also have that wood [palm] wine that I have already spoken about. Here’s another curiosity that needs to be mentioned: in this kingdom there is flour made from trees. This is how they get it: there are special, large and thick trees here, and they are full of flour. Their bark is thin, and inside there is only flour; They make delicious dough from it. We tried and ate it many times.”

This is a quote from an earlier manuscript written in Old French, the lingua franca of Southern Europe at the time. In a later manuscript, published in 1556 by the Venetian Giovanni Ramusio, there is also addition: “If you remove the first thin bark, you reach wood three inches thick, and the core is all filled with flour, like carvolo (the fruit of a tree that produces a mealy substance. - Ed.). The trees are so thick that only two people can grasp them. Residents put that flour in tubs filled with water and stir the water with a stick; then bran and other impurities float to the surface, and clean flour sinks to the bottom. Then the water is poured out, and clean flour is taken and cookies and various kinds of pies are made from it. Mister Marco ate them many times and brought them with him to Venice; they look and taste like barley bread.”

The plant in question is known as the sago palm. Groats, obtained from its trunk, is quite popular in Asia and is used to prepare a wide variety of dishes. But the “cookies and various kinds of pies” reported in Ramusio’s manuscript are not very similar to pasta. Where did the references to pasta come from then? It turns out that if you look into Italian-speaking publications memoirs of Marco Polo, then we will encounter the word pasta more than once. The fact is that originally in Italian it meant thick mushy mass, as well as dough. Therefore, the above mention of flour, from which “tasty dough is made,” is an example of a correct translation. But, according to scientists, Marco Polo does not mention a dish called “pasta” in his early manuscripts, although in a number of English translations of the 19th century this word is conveyed without changes - pasta.

Moreover, even if Marco Polo mentioned pasta as a dish (some sources also lead the word lagana is an old designation for the prototype of either lasagna or tagliatelle pasta), this would mean that he was already familiar with these dishes and their names in Italy. Then the Chinese version with pasta plagiarism looks even more absurd.

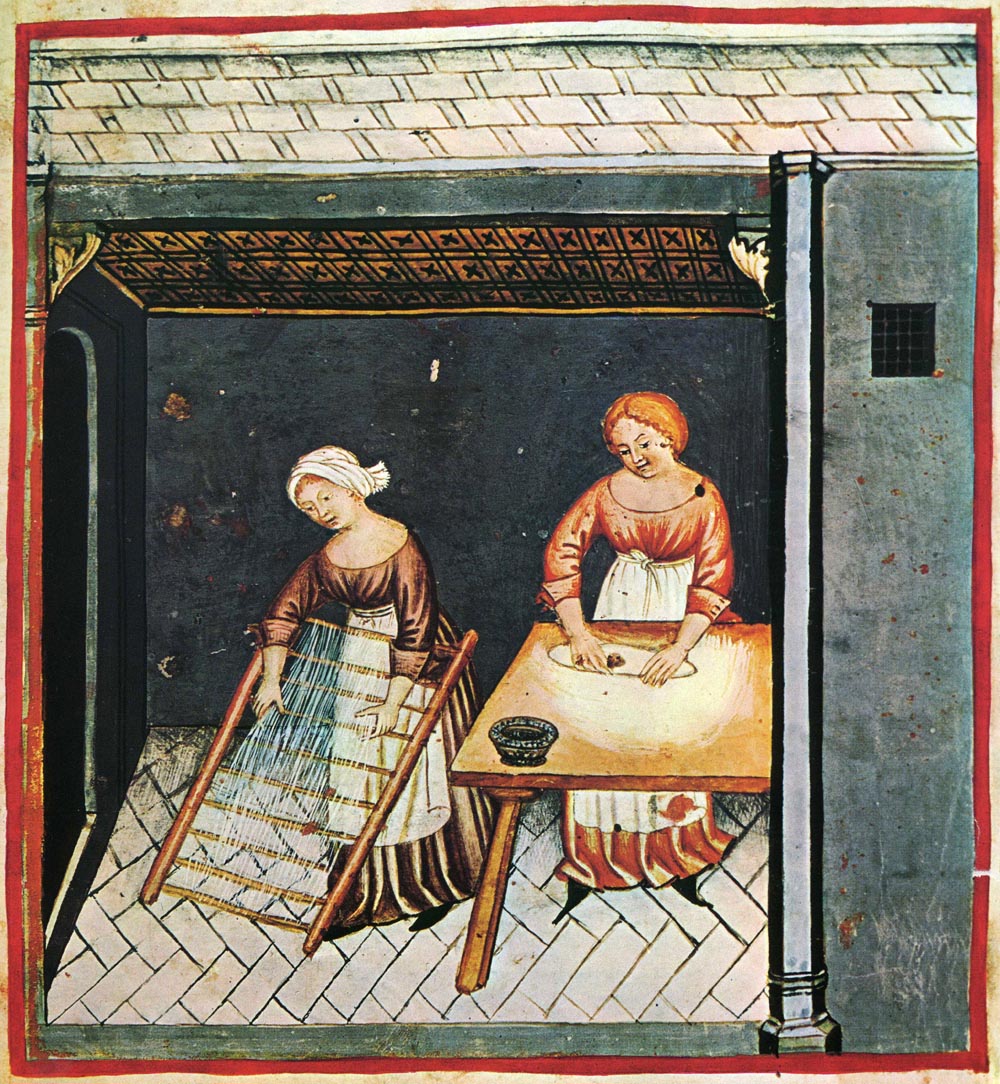

Indeed, there is a lot of evidence of the prevalence of pasta in the Apennines long before the return of Marco Polo from Asia. In an Etruscan tomb of the 4th century BC. e. were found devices that bear a striking resemblance to those used to make pasta. Pasta-like product described in the cookbook of Appicus, a Roman chef who lived in the 1st century AD. e. under Emperor Tiberius. The famous Arab traveler of the 12th century al-Idrisi, talking about his visit to Italy, mentions the dish itriya ("strip"), which is still used today to refer to spaghetti in the Sicilian dialect.

Legal documents have also reached us. According to one paper, dated August 2, 1244, the Bergamo physician Ruggero di Bruca undertakes, on the basis of an act drawn up by the notary Gianuino de Bredono, to cure a patient of an oral disease. The patient, in turn, undertakes not to consume certain products, among which “smooth paste” is mentioned. Also reached us was a document compiled on February 4, 1279 in Genoa will a certain Ponzio Bastone, who, among other things, left his heirs a basket full of pasta (apparently dried). Thus, Marco Polo could not introduce the inhabitants of the Apennines to pasta or its analogues - they had long been popular in his homeland. Although this does not negate the fact that an analogue of pasta could have been known in China even before the Etruscans, as shown excavations.

As for the reasons for the spread of the legend of Marco Polo bringing pasta to Europe, according to one theory, the American magazine The Macaroni Journal is partly to blame. In October number (p. 32) of this publication in 1929 a story was published about a sailor from the ship Marco Polo named Spaghetti, who spied how the inhabitants of the Chinese coast were preparing a dish that was strange to him. The story was completely fictitious, but it seems to have left its mark on the information field.

Not true

Read on topic:

1. The Twisted History of Pasta

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.