According to popular legend, the most famous miner in the Soviet Union was forced to change his name due to a curious error in a central newspaper. We checked if this is true.

Here's what the story says "RIA Novosti": “Andrei Stakhanov woke up famous 75 years ago, on the morning of August 31, 1935. <…> The Pravda newspaper immediately trumpeted the pre-planned feat of a worker who allegedly personally produced 102 tons of coal during a shift instead of the required seven. But the telegram from the mine did not indicate the full name of the hero, but only the initial “A.”. Journalists, without thinking twice, decided that his name was Alexey. When the mistake became clear, Comrade Stalin said: “The newspaper Pravda cannot be mistaken.” The ascetic had to change his passport and turn into Alexei. How he reacted to this remained unknown, and again no one asked him. It’s good that they didn’t replace the name with a number, like the prisoners of Stalin’s camps. The Stakhanov movement began with that well-prepared feat. Our hero continued to break records, and his assistants still remained nameless."

The famous Soviet journalist Yaroslav Golovanov in his “Notes of your contemporary” confirms legend, but gives a different quote from Stalin: “Alexey... A beautiful Russian name... I like it.” This story is also reported with certain details BBC, Lenta.ru And "Moscow 24". On "Rambler" it is clarified that Stakhanov’s name was either Andrei or Alexander.

Let's leave aside the questions of the artificiality of Stakhanov's records or his broken life - they require a separate detailed investigation. We are purely interested in the issue of changing the name.

Needless to say, after his record, A. G. Stakhanov (let’s call him that for the sake of correctness) became a cult personality. During Soviet times, dozens of articles were written about him. books and published hundreds interview, and the miner himself noted memoirs. However, they did not address the issue of a forced name change. This is understandable - if the authority of Stalin in the last years of the life of the Hero of Socialist Labor (Stakhanov died in 1977) was seriously doubted, then the reputation of the newspaper Pravda, the main organ of the Soviet press, could not be lowered.

Gazeta.ru notes that the very article in Pravda that changed the miner’s life came out “a couple of days later” after his impressive achievement and was called “The Miner Stakhanov’s Record.” Indeed, on the last page of Pravda for September 2, 1935 there is a small note:

As you can see, in it the record holder is simply called “Comrade. Stakhanov", without name. It turns out that if Stakhanov “renamed” the article in Pravda, then at least not the first.

In 2012, on the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the death of Alexei Stakhanov, the Ukrainian newspaper Segodnya contacted his daughter Violetta. Among other things, the journalist raised the issue of his father changing his name. Violetta Stakhanova was born in 1940, so she was not a witness to famous events, but here’s what she answered: “At home I never heard anyone call him Andrey. When we came to his homeland in the Oryol province, the sisters always called our father Lyoshka. Claudia was born in 1933 - the older sister, the brother was born in 1934 - even before the record, and they also have the middle name Alekseevich. In general, in our family they never said that my father’s name was something else. Mom told me everything, I don’t think she would have missed the renaming. And the Stakhanovs didn’t have Andreev relatives, but they did have a great-grandfather, Alexei. It’s already a tradition to name someone after a grandfather or great-grandfather. We also named our grandson Alexey, in honor of his grandfather. He’s 17 now and finishing school.”

In another interview with Violetta Stakhanova scattered rumors that her father's real name was Stakanov.

The earliest mention of the expression "Truth can't be wrong" and its variations in accessible print dates back to 1978. In foreign collected works Alexander Solzhenitsyn, it explains why one of the writer’s stories, once published in the main newspaper of the country, was later, during the period of his disgrace, never criticized in the Soviet press. But in connection with Stalin or Stakhanov, such a quotation was not published in Soviet times. As for the quote given by Yaroslav Golovanov (“Beautiful Russian name”), in his notes it is dated February-March 1984. Before this, it also does not occur in the specified context.

Where then did the story about Stakhanov come from, which is not confirmed either in the press or in reports from relatives? Where are its roots?

In many articles about the famous miner mentioned his colleague Nikita Izotov, who also worked in the Donbass and three years before Stakhanov’s record, organized his own Izot movement to improve the skills of workers. He became one of the founders of the Stakhanov movement, later blocking the achievement of his eminent colleague.

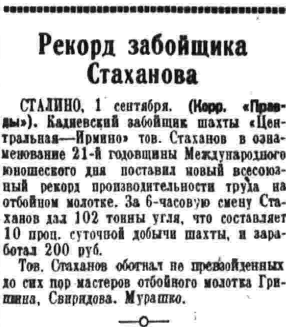

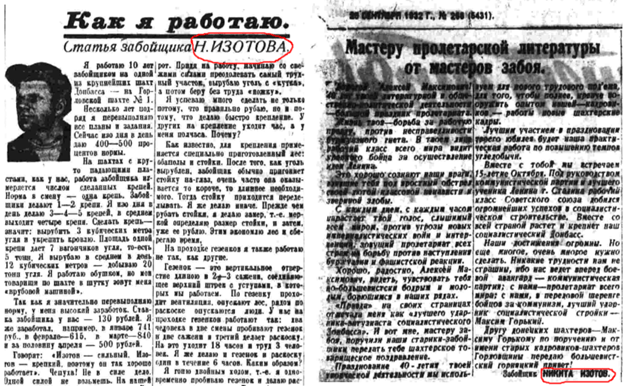

So, back in the 1960s, in many publications A biography of Izotov was published, written by journalist Semyon Gershberg and later even included in the ZhZL series (vol. "Innovators"). From it you can find out that the Izot movement originated in 1932 after the newspaper Pravda on May 11 published an article by a miner entitled “My Method,” in which he spoke in detail about his coal mining technique. However, the article for the miner, based on his story, was written by the same Gershberg, then still a young Pravda correspondent sent to Gorlovka. And, as the journalist recalls, the article went to Moscow with an initial (N. Izotov), and after asking for the full name of the miner, the mine manager replied that his name was Nikita. And only a year later, Izotov’s wife informed Gershberg that the miner’s name was not Nikita, but Nikifor (the family’s affectionate Nikisha could have caused confusion). Then the miner went to Moscow for an appointment with Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and when he called Izotov Nikita, and the worker corrected him, the party leader replied: “Do you want to know my opinion? The glorious name is Nikita.” As a result, the interlocutors agreed that it would be better for Nikita to remain Nikita.

As you can see, the story with the name of Izotov almost completely repeats the story of Stakhanov (down to the rhyme “beautiful Russian name Alexey” and “glorious name Nikita”), but at the same time it happened earlier, gained fame earlier and has a witness in the person of a direct participant in those events. And although Gershberg is somewhat mistaken in the details here (Izotov’s article was called “How I Work,” and only the initial remained from Izotov’s name), there are other confirmations of the story. In particular, in another Soviet biographies Izotov, in a conversation with Ordzhonikidze, clarifies that the mistake happened in another note (“Two years ago, my congratulations to Gorky were printed in the newspaper. “To the master of literature from the masters of slaughter.” And they signed it, “Slaughterer Nikita Izotov,” so that they have a mouse in their bosom...”). Gershberg himself will correct his mistake in a few years, notingthat we are talking about the September issue of Pravda:

Thus, the real person involved in the story about the name change turned out to be another record-breaking miner, Nikita (Nikifor) Izotov, and Stakhanov got into it, apparently, due to the effect of false memory, after which the story acquired new details.

Most likely not true

Read on topic:

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.