As numerous publications testify, at the end of the 19th century, a descendant of the founder of the famous Irish company bought a slave girl in the Congo only to sketch her being killed and eaten by the natives. We checked to see if this was the case.

This is what information can be learned from the text, in one form or another, walking around social networks last few years:

“In 1890, the heir to the Jameson Whiskey fortune was accused of an act that the company prefers not to mention: in 1888, he bought an 11-year-old girl as a slave so that he could then watch her be eaten by cannibals. This happened during an expedition to the Congo, where James S. Jameson enlisted to provide humanitarian aid.

Already on the spot, the translator consulted with local leaders, who agreed to show the process of preparing and eating human flesh. After which Jameson led the girl to the cannibal shack, where, through an interpreter, he said:

“It’s a gift from a white man who wants to watch her get eaten.”

Jameson watched the process all this time and made sketches with watercolors. The latter, unfortunately, have not survived.

"Cannibal" James Sligo Jameson died of fever in 1888."

IN some publications Additional details are also reported: for example, it is stated that the price of the girl was six handkerchiefs. The text is also popular in some Russian-speaking languages. websites, and - to a greater extent - on Western resources.

Here's what we know about this complicated story so far.

James Sligo Jameson, great-grandson of the founder of a famous whiskey company, in 1887 joined expeditions to rescue Emin Pasha (Eduard Schnitzer), the converted governor of the colonial province of Equatoria in Central Africa, who, as a result of the uprising, was cut off from British troops. The expedition was led by a famous traveler and journalist Henry Morton Stanley. Jameson's second goal was to explore the colonial territories in the Congo.

August 17, 1888 Jameson died in the territory of modern Congo from some type of typhoid fever. He was 31 years old. After his death, a scandal developed around his name based on the messages of the Syrian translator Assad Farran. Already in September, the first article appeared in the Scottish Aberdeen Journal. note, which reported Farran's grisly description of a bloody orgy. According to the latter, the late Jameson watched everything with interest and asked that the murder of the woman be postponed until he had made a sketch.

However, in the same September, newspapers published and the text of Jameson's last telegram to his wife. It read: “The reports about me coming from Asad Farran, the famous translator, are false. If they go public, stop them."

At the same time, The Times of London published letter William Burdett-Coutts, a member of the House of Commons, who said he witnessed Farran signing a "strong denial" of his own account. Burdett-Coutts claimed that in a private conversation Farran described his story as retaliation for his own dismissal.

It would seem that the scandal was extinguished. However, two years later, in November 1890, a long and detailed story Farran about the same events. According to the translator, Jameson “really wanted to see a man killed and eaten by cannibals,” and during a stop in the village of Riba-Riba, he made a corresponding request to one of the local leaders. The Englishman was told in response that in order to fulfill his wish, he would need to buy a slave and then present it to the aborigines as a gift. After agreeing on a price of six handkerchiefs, Jameson allegedly purchased the slave, who turned out to be "a girl about 10 years old." The girl was stabbed and eaten, while Jameson made six sketches, which he later outlined in watercolors.

The next day The Times published letter Jameson himself, allegedly written on August 3, 1888, two weeks before his death. The letter was provided to the newspaper by his wife Ethel. Jameson claimed that he was greatly frightened by the scenes of violence and murder, insisted that he did not make sketches on the spot, and it all happened because of his dispute with a local Arab who was trying to prove to Jameson the reality of the phenomenon of cannibalism: “He, laughing, said: “Give me some cloth and see what happens.” I just thought that this was another one of their plans to get something from me, and... I sent for a small bundle of six handkerchiefs... What followed was the most terrible scene that I have ever seen in my life... Small sketches were made in the evening in my house.”

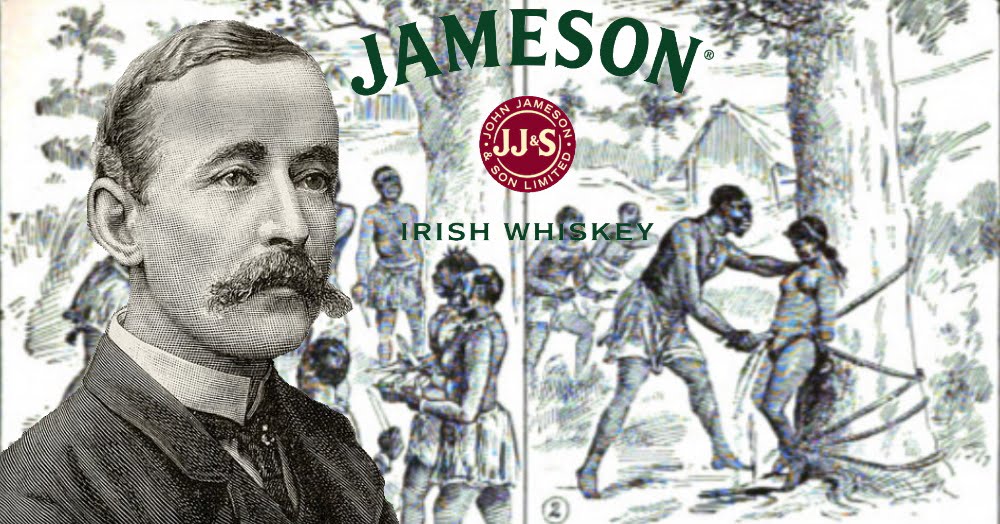

Also, Jameson's widow attached to the letter the same refutation allegedly signed by Farran back in September 1888. It read: “I, Assad Farran, who recently served as interpreter on the expedition to help Emin, declare that the story of Mr. Jameson's purchase of the girl has been completely misinterpreted. The story is completely false, and I declare such an accusation against Mr. Jameson to be unfounded. The six handkerchiefs were a gift from Mr. Jameson and had nothing to do with the incident with which, owing to the above-mentioned misunderstanding, they were erroneously connected.”

It is important to note here that Farran's refutation partially contradicts the words of Jameson himself, who argued that the connection of scarves with cannibalism did occur. In addition, the translator's refutation is dated two years earlier than his signed statement with the "bloody history."

In 1891, Ethel Jameson edited and published report her husband about the expedition, consisting of various letters and diary entries. This version dates the cannibalism story to May 11, 1888. In the report, Jameson writes: “Until the last moment I could not believe that they were acting seriously. I heard many similar stories... but until the very end I could not convince myself that this was anything other than a ploy to get money out of me.”

Despite the complexity of this whole story, in which the evidence is only letters and confessions of two alleged defendants, we can conclude that Jameson actually witnessed the murder of a girl by cannibals, however, most likely, this was not “the purchase of a slave for the purpose of killing.” At the very least, Farran’s own refutation cannot be ignored. As for the sketches, only their supposed ones have reached us. copies, made by another member of the expedition, James Buell.

Half-truth

Read on topic:

1. Did a Jameson Whiskey Heir Buy a Slave Girl to Watch Her Get Cannibalized?

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.