According to popular legend, German lost only one vote to English when choosing the official language of the United States at the end of the 18th century. We checked to see if this was the case.

Here's what you can read at website foreign language schools Start2Talk: “Few people know that German once almost became the official language of the United States. The Continental Congress, held during the Revolution in Philadelphia, planned to adopt a new language that would help completely sever ties with Great Britain. German, French and Hebrew were suggested as possible options. But when it came to voting, familiar English still won, with a margin of only one vote!”

Similar information is present on the pages of other linguistic portals, as well as in the book by V. P. Fedorov “Germany: 80s. Essays on Social Morals" In some places it is generally said that the decisive vote for the English language was cast by a German.

Let's start with the fact that in the USA there is no official (or state) language, although attempts to proclaim English as such periodically are being undertaken. English is the de facto common language - it is spoken by about 78% of the country's population. Native speakers of German make up 0.38% of the population, or just over a million people. Only in the state of North Dakota is this language the second most popular, and then with a modest result 1.39%.

However, this was not always the case, and other impressive numbers: About 50 million US citizens are of German descent - morethan any other ethnic group in the country. German was the second most widely spoken language in the region for more than two centuries, beginning with the mass emigration of residents of the German Palatinate to Pennsylvania until the beginning of the 20th century. It was spoken by millions of immigrants from Germany, Switzerland, Austria-Hungary and Russia, as well as their descendants. Churches, schools, newspapers, factories and factories - German was present everywhere. As early as 1751, Benjamin Franklin, observing a sharp increase in the number of immigrants from Germany, wrote:

“Why should we tolerate the dominance of Palatinate peasants in our settlements? Why should they cluster together, impose their own language and manners, and supplant ours? Why should the colony of Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of strangers, who will soon become so numerous that they will Germanize us instead of us Anglicizing them? They will never accept our language or customs, just as they cannot accept our appearance."

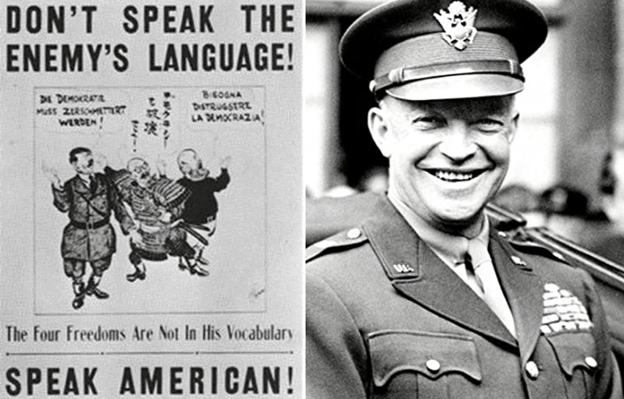

The situation changed with the entry of the United States into the First World War. The struggle of the descendants of German immigrants for their language and culture came to naught the moment Germany became an enemy of the United States. This was, on the one hand, an unprecedented patriotic upsurge and the formation of a national American consciousness, and on the other hand, the fear of being accused of treason. As a result, ethnic Germans began to change their surnames en masse to English-language ones (Schmidt to Smith, etc.), works of great German composers disappeared from concert programs, and the teaching of the corresponding language was banned in at least 14 states. The last initiative was ended by the US Supreme Court in 1923 recognized all such reforms in education are unconstitutional. Nevertheless, the process of assimilation could no longer be stopped. Negative characters in the most popular films began to speak with a German accent, and the Second World War completed the matter. The posters urged not to speak German, Japanese and Italian, and the main creator of victory in the eyes of the Americans was the descendant of German emigrants, and now one hundred percent American, Dwight Eisenhower:

But let's return to the situation of the German language in the first years of the country's independence. The story we are considering appears to be based on happeningwhich occurred in 1795.

On March 20, 1794, a group of German settlers from Virginia submitted a petition to the US House of Representatives demanding that federal laws be published not only in English, but also in German. In response to this, the House committee recommended that 3,000 copies of the collection of laws be published in German and distributed to those citizens who do not know English. And although the committee tentatively approved the petition, when it came to discussion among congressmen, it turned out that it did not have much support. The debate dragged on, and as a result, on January 13, 1795, a vote took place with a different wording: should consideration of this issue be postponed to a later date? This proposal was rejected with a vote ratio of 42:41. A month later, the issue was considered again. During the debate, Rep. Thomas Hartley of Pennsylvania said, “It would be desirable for the Germans to learn English, but if our goal is to provide up-to-date information, we must do it in a language that is understandable. Older Germans cannot learn our language in one day.” It was objected to Thomas that the Welsh and Scots, who had not spoken English for centuries, nevertheless somehow lived in Great Britain. Thus, the project to publish American laws in German was rejected.

It is at this point in our history that the figure of the German “with a decisive vote for the English language” appears. The January vote to adjourn is sometimes called the "Muhlenberg vote" after the House Speaker, who is said to sources, spoke little German, since his family had managed to assimilate. It is believed that Muhlenberg did not take part in the vote on the transfer and even statedthat “the sooner the Germans become Americans, the better.” Most likely, Muhlenberg's vote could not influence anything, since even if it was transferred, there was no sufficient support (as subsequent discussion showed) the initiative did not have. And most importantly, this was not a vote at all for the official status of the German language in the country. Why did Frederick Muhlenberg get involved in this story in the first place? Most likely because a year later he cast the decisive vote for the so-called Jay's law - an act that established partnerships with yesterday’s enemy, Great Britain, and caused a serious crisis in the political elite of the United States.

Nevertheless, half a century passed, and the German lawyer Franz von Locher in his book The History and Achievements of the Germans in America, he accused Muhlenberg of dooming the German language to the status of a minority language. Löcher argued that the vote was not held in the US House of Representatives, but in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives (both bodies then met in the capital of Philadelphia), and the topic of the vote was the choice between German and English on the issue of the official language of the state. Muhlenberg, Löcher wrote, voted for English at the decisive moment. Despite the obvious historical inconsistencies, von Locher's work became widespread and greatly contributed to the formation of the legend of the “traitor” Muhlenberg. And the legend received a second birth in the 1930s, when the Nazis tried give legitimacy to the historical myth of an “almost German America.” And only in 1982 were Congress workers able to properly understand the documents, restoring the course of distant events.

Thus, German never came close to becoming an official language in the United States.

Not true

Read on topic:

1. German as the Official Language of the United States

2. Here's A Good Book That Will Grab You

3. The Legendary English-Only Vote of 1795

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.