In collections of entertaining facts and other literature, you can often find a statement that in the state of Indiana, the value of pi at the legislative level is equal to 4 - for the convenience of calculations. We checked if this is true.

In the post-Soviet space, this funny fact has been known since the times of the USSR. For example, in 1991 it was included in the domestic publication Guinness Book of Records with reference to a certain Bill 246, passed by the State General Assembly. And in our time, this information appears in various publications (often in collections of ridiculous American laws). For example, in "Tver linguistic meridian", magazine "New Crocodile" and such authoritative sources as the magazine "Kommersant Power" And "Parliamentary newspaper". But in the book “100 Great Scientific Achievements of Russia” a different meaning of the constant is given - there approvedthat in Indiana, pi is 3.2.

People know from school that the number pi (π) - the ratio of the circumference to its diameter - is irrational, that is, cannot be represented as an ordinary fraction. Typically, in household calculations, a rounded value of 3.14 is used, although it is not at all suitable for more accurate and important measurements.

But let's first turn not to the problems of the number pi, but to such an insoluble problem of antiquity as squaring a circle - using a compass and a ruler to construct a square equal in area to a given circle. Mathematicians struggled with this problem for many centuries, but only in 1882 Ferdinand von Lindemann proved the futility of all potential efforts in this matter. And if scientists around the world quickly learned about a disappointing, but generally quite expected conclusion, then non-professionals did not give up hope.

In 1888, Indiana physician and amateur mathematician Edward (Edwin) Johnston Goodwin decided he had made a discovery and spent several years trying to tell the world about it. On the eve of the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893, he managed to negotiate with the organizers to allocate a pavilion for “giving scientific lectures.” However, soon the exhibition management, having familiarized themselves with Goodwin’s calculations, notified him of their refusal. The amateur mathematician did not lose heart and in July 1894 published article about his scientific victory not just anywhere, but in the American Mathematical Monthly, the leading publication in its field. True, with the note “published at the request of the author” and a complete disclaimer of liability on the part of the publication. The publishers could not help but see that the article was full of errors. Firstly, Goodwin did not understand that the problem was to construct an equal square without measuring instruments (the ruler should not have divisions), and not to find the length of its side. Secondly, he argued that the areas of a circle and a square are equal if the perimeter of the latter is equal to the length of the circle, which, to put it mildly, is incorrect.

Without discovering errors in his reasoning or hiding them, Edwin Goodwin decided to take a new height. He persuaded Taylor Record, a state member of the House of Representatives from his home county of Posey, to introduce an act to the Indiana General Assembly that would enshrine Goodwin's findings into law. Goodwin's main argument was that his native Indiana would save money thanks to his discovery. After all, once the “truth” has been revealed, no one can ignore it. And Goodwin was going to receive royalties for the use of his discovery (primarily for educational purposes), but the mathematical genius allowed the authorities of Indiana to use his formulas for free. Farmer and timber merchant Taylor Record, who spent his first and last term as a representative, did not understand anything about the mathematical part, but soon entered the House of Representatives Bill 246.

This bill had many wonderful details. For example, section 3, where it was said that Goodwin's solutions to the problems of squaring a circle, doubling a cube, and trisecting an angle (three unsolvable classic construction problems) have already been recognized for their contributions to science by the American Mathematical Monthly. As we showed above, this was not true.

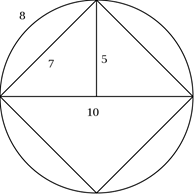

In addition, you cannot ignore the figure described in section 2:

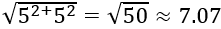

This is a circle with a length of 32 and a diameter of 10, into which a square with a side of 7 is inscribed. The sides of the depicted square, according to the Pythagorean theorem, must have the length:

which is not equal to 7. Nevertheless, Goodwin concludes from this that the circumference and diameter are related as 4 to 5/4, that is, 3.2 to 1. And although the number pi does not appear in the bill, it follows from it that this constant is equal to 3.2. Not 4, but 3.2.

On January 18, 1897, House Bill 246 passed the Indiana House of Representatives. The subject of the bill and the abundance of unfamiliar Greek words caused some confusion among the people's representatives. First, it was proposed to send the act to the Finance Committee for approval. Then - to the swamp committee, where it will “find a well-deserved grave.” In the end, the paper ended up in the hands of the Education Committee, which, oddly enough, responded positively to the project, as a result of which it was adopted by the House of Representatives on February 6, 1897 (vote distribution 67:0). So, half the job was done, all that remained was to convince the Senate.

But unfortunately for Edwin Goodwin, a day earlier, Professor Clarence Waldo, head of the mathematics department at the prestigious Purdue University, arrived in Indianapolis and was tasked with lobbying for the budget of the State Academy of Sciences. The last thing he expected was to get into a discussion of a mathematical law. Waldo was shown a copy of the bill and offered to introduce him to its author. The professor refused, saying that he had been introduced to enough crazy people. Moreover, he had a serious conversation with the senators, explaining to them the real state of affairs with the squaring of the circle.

As a result, when the bill reached the Senate, it was received coolly there. The temperance committee that reviewed the application gave its approval, but on February 12, 1897, the Senate postponed the adoption of the bill indefinitely. The decisive argument was one of the senators that the General Assembly did not have the power to determine mathematical truth. The campaign to ridicule the law launched in the press also played an important role:

How wrote Indianapolis News after the crucial session, “Senators made puns about the law and ridiculed it. The fun lasted for half an hour. Senator Hubbell said that the Senate, whose meetings cost the state $250 a day, should not waste time on such frivolities. He said his study of the leading newspapers of Chicago and the East led him to the conclusion that the Indiana legislature had made a mockery of itself by the measures already taken in regard to the bill." Since then, the scandalous bill has not been returned to.

20 years later Professor Waldo suggestedthat only the intervention of the Academy of Sciences prevented this monstrous act. “If this conclusion is correct,” he added, “then this act of prevention alone was worth more to Indiana, jealous of her honest reputation, than all her past and future contributions to the publication of the minutes of the meetings of the Academy of Sciences.”

Physician and amateur mathematician Edwin Goodwin died in 1902, just five years after the bill's notorious incident. As his obituary stated, “He thought he had made a great discovery and wanted to benefit the world with it. <…> Years passed, and when he saw that the brainchild of his genius was still not accepted by the scientific world, he was disappointed, although he never lost hope and believed that before the end of his days he would see the world realize the greatness of his plan and enjoy a moment of glory. His aspirations were not destined to come true, and the tragedy of fruitless ambitions played out in the peaceful interiors of village life.”

As we can see, despite all the dramatic events that unfolded around the problem of squaring the circle, the Indiana legislature never finally made a decision regarding the number pi and such a law has never been and is not in effect.

Mostly lies

Read on topic:

1. In Celebration of Pi Day: The History of the Indiana Pi Bill

2. House Bill No. 246 Indiana State Legislature

3. Hallenberg, Arthur E. House Bill No. 246 Revisited.

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.