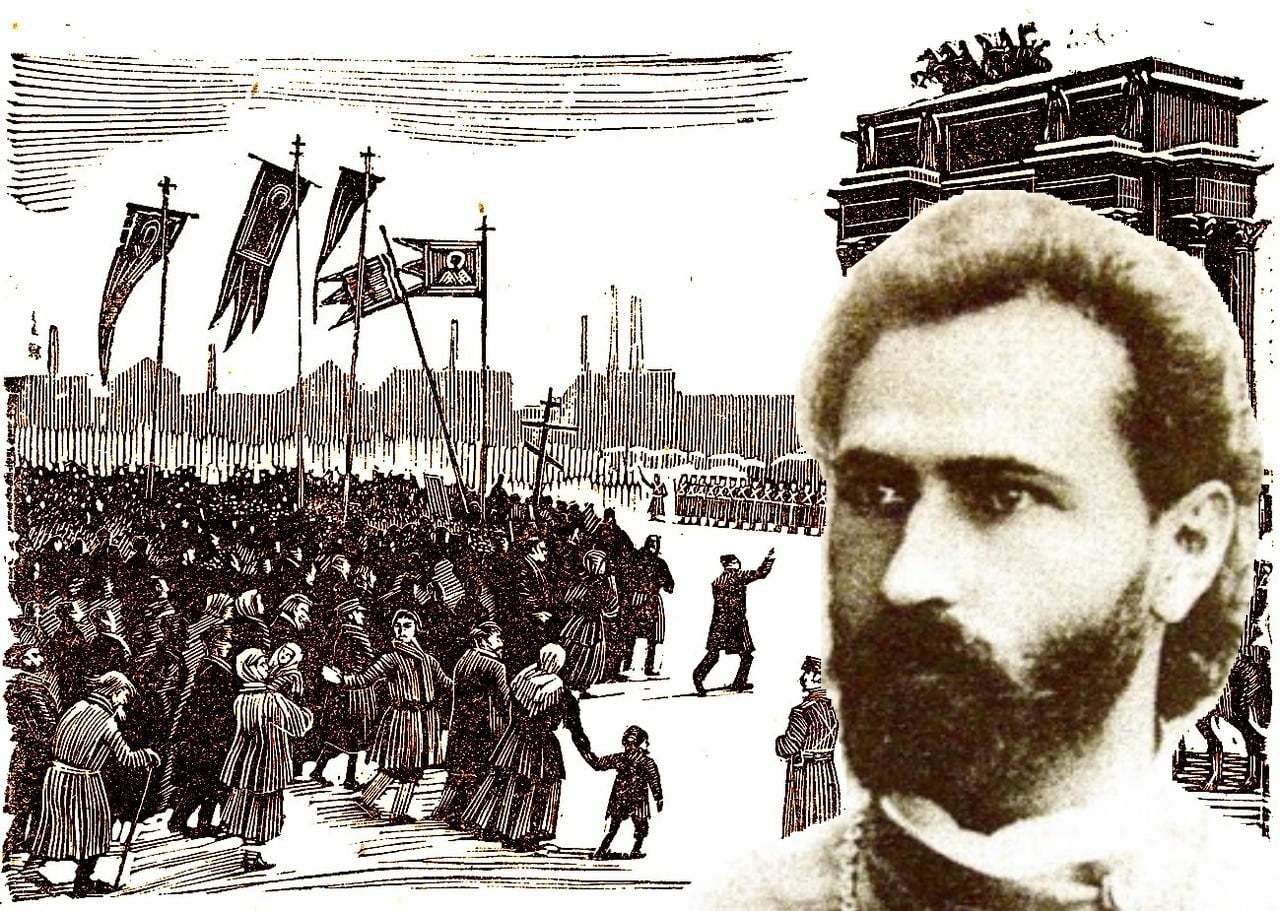

It is known from historical literature that the priest who organized the 1905 procession, which ended with Bloody Sunday, was a provocateur in the service of the Security Department. We checked if this is true.

The events of January 9 (22), 1905 in St. Petersburg, which went down in history as Bloody Sunday, became one of the links in the chain of events that shocked Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and affected the subsequent fate of the country right up to the present day. The brutal dispersal of a peaceful march, the purpose of which was for workers to present a petition to the Tsar, ultimately led to what is called the First Russian Revolution.

The reasons for the excessive brutality of the troops (up to 200 demonstrators died) are still being debated. The identity of the main ideologist of the injured party is no less controversial. The procession was organized and led by Georgy Apollonovich Gapon, a priest and active public figure. Being slightly wounded, he fled abroad, where he continued revolutionary propaganda, and soon after his return, in March 1906, he was killed. Great Soviet Encyclopedia claimed, that it was a "trial of a group of workers", while, for example, in the complete works of Lenin it was saidthat Gapon “was killed by the Social Revolutionaries.” The reason was usually given as betrayal of the ideals of the revolution and provocative work for the tsarist secret police. This is how Gapon's activities was described in “A Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)”, published in 1938 under the editorship of J.V. Stalin:

“Back in 1904, before the Putilov strike, the police, with the help of the provocateur priest Gapon, created their own organization among the workers - the “Meeting of Russian Factory Workers.” This organization had its branches in all districts of St. Petersburg. When the strike began, priest Gapon, at meetings of his society, proposed a provocative plan: on January 9, let all the workers gather and, in a peaceful procession with banners and royal portraits, go to the Winter Palace and submit a petition (request) to the Tsar about their needs. The king, they say, will come out to the people, listen and satisfy their demands. Gapon undertook to help the tsarist secret police: to cause the execution of the workers and drown the labor movement in blood.”

Soviet school textbooks also echoed the “Short Course”. The phrase “Pop Gapon” has become synonymous with the word “provocateur.” And judging by the frequency useI in modern media, the phrase fulfills the same role today. One of the reasons for this is articles and books in which Georgy Gapon continues to be declared a provocateur with enviable consistency. The only difference is that he has now become the target of monarchists, who accuse him of bloody provocation in order to spark a revolution. Gapon was named as an agent in article from the newspaper “Versia”, posted on the website of the FSB of the Russian Federation.

To begin with, it is necessary to give a correct definition of the concept of “provocateur”. And here we are faced with three options at once.

No. 1. Nowadays, the main meaning of the word “provocateur” is a person who arranges provocations. That is, Georgy Gapon would be a provocateur in the everyday understanding if he led the people to the predicted massacre for the sake of effect.

No. 2. The historical, narrower concept of “provocateur” is a completely different matter. So was accepted to name secret agents of the police or political investigation who came into contact with potential violators of criminal law with the aim of first inducing them to certain illegal actions, and then “exposing” them and arresting them. That is, in this sense, Gapon is required not just to organize a provocation, but to coordinate all this on the part of the state security agencies.

No. 3. There is a third option, which became widespread at the beginning of the 20th century, during the era of revolutionary circles. About him spoke out Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin at a meeting of the State Duma on February 11, 1909: “According to revolutionary terminology, every person who delivers information to the government is a provocateur; in a revolutionary environment such a person will not be called a traitor or traitor, he will be declared a provocateur.” That is, in the third sense, Gapon had to be simply an agent, “sent by a Cossack” in order to be called a provocateur. And it is not at all necessary that this be accompanied by any illegal actions.

Georgy Gapon entered the socio-political arena of the Russian Empire when in 1904 he organized and headed the legal (and importantly) public organization “Meeting of Russian Factory Workers of St. Petersburg.” This was not a revolutionary circle, but a typical trade union, based on another organization - the St. Petersburg Society for Mutual Assistance of Workers in Mechanical Production. The “assembly” not only enjoyed the favor of the authorities - its activities at first took place under the auspices of the Police Department. How writes famous historian Alexander Bokhanov, “the authorities sought to take on the role of an impartial arbiter in disputes and conflicts between workers and entrepreneurs, to give the working people hope and support against the “sharks of capitalism” and “predators of profit.” The system of organizing such trade unions was called “Zubatovism” - in honor of Sergei Zubatov, the ex-chief of the Moscow Security Branch and the Special Section of the Police Department. It is Zubatov who is rightly called the creator of the political investigation system in Russia. And it was Zubatov who was the founder and first leader of the prototype of Gapon’s organization - the St. Petersburg Society for Mutual Assistance of Workers in Mechanical Production.

Here we come to the main argument of supporters of Gapon’s agent provocateur theory, namely contacts with the police. Yes, of course, after Zubatov left the trade union and the reorganization undertaken by Gapon, the “Assembly’s” relationship with the Police Department did not break completely. However, their character has changed. How wrote Gapon To Zubatov, “we do not hide that the idea of a unique labor movement is your idea, but we emphasize that now the connection with the police is broken (as it actually is), that our cause is just, open, that the police can only control us, but not keep us on a leash.” In other words, it was a kind of Gaponov’s “we'll go the other way" By certificate the future head of the St. Petersburg security department, Alexander Gerasimov, “placed by the head of the political police in such a responsible position, Gapon was left to his own devices almost from the very beginning, without an experienced leader and controller... There was no talk of police control over the activities of society for a long time. It was an ordinary society with real workers at the head. In their midst, Gapon completely forgot about the thoughts that guided him at the beginning.”

At the same time, Georgy Gapon personally continued to cooperate with the Police Department and even received considerable money from it. But this cannot in any way be called undercover activity. As Gerasimov and Major General of the Separate Corps of Gendarmes wrote Spiridovich, Gapon was invited to cooperate with the Police Department not as an agent, but as an organizer and agitator. Gapon's mission was to combat the influence of revolutionary propagandists and convince workers of the benefits of peaceful methods of fighting for their interests. The police department, considering this activity useful for the state, supported Gapon and from time to time supplied him with money. Gapon himself, as the head of the “Assembly,” met with officials from the Police Department and reported on the state of the labor issue in St. Petersburg. Gapon did not hide his relationship with the Police Department and the receipt of money from it from his workers. During his short stay abroad after Bloody Sunday, Gapon wrote autobiography, in which he confirmed the fact of receiving money from the police.

In other words, in the memoirs of both of the above-mentioned leaders of political investigation, Gerasimova And Spiridovich, who described their relationship with Gapon in some detail, there is no hint that Gapon was used by Zubatov or his successors as a secret employee. From Gerasimov’s memoirs, we can conclude that the only attempt to involve Gapon in undercover activities took place in 1906, after his return, and ended with the murder of the priest. Moreover, the person who organized the murder of Gapon was, as it is believed, Yevno Azef - a very real agent provocateur in the service of the police. As the head of the terrorist wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries, he easily convinced his comrades that Gapon had betrayed the cause of the revolution, sold himself to the police, and insisted on his murder. So Gapon, on the contrary, turned out to be a victim of provocation. Moreover, from the end of 1904 until Bloody Sunday, his relations with the police ceased, and the day before the tragedy he was generally announced wanted Thus, if Gapon’s actions on January 9 were a kind of provocation, then it was not his personal one, nor with the police or secret police.

Another important argument against the version of an agent provocateur is associated not with memories, but with official documents. Firstly, until 1905, Gapon legally could not be an agent of the Security Branch, since the law prohibited the recruitment of representatives of the clergy as agents. Secondly, Gapon was not involved in intelligence activities as such. There is no information about the arrest or punishment of at least one person who was issued on his tip. Not a single denunciation written by Gapon has been identified. According to the historian I. N. Ksenofontova, all attempts by Soviet ideologists to portray Gapon as a police agent were based on manipulation of facts. The fact is that the concept of a secret police agent in the Russian Empire meant a very specific legal status. The police could not base their activities on unverifiable sources, and certain documentation was kept for each person who delivered intelligence information. All this data was stored in a special secret archive of the Police Department in St. Petersburg. After the February Revolution, the archive was opened, and several special commissions began studying its contents. According to scale research Z.I. Peregudova, in total, in the file cabinet of the Police Department archives there were about 10,000 agents of all stripes who worked for the police from 1870 to 1917. According to experts, neither the Police Department files nor other files and archives contain information about an agent named Georgy Gapon. Moreover, more than 100 years have passed since Gapon’s death, and at least something during this time should have surfaced.

As for the label of a provocateur attached to Gapon by the Soviet authorities, there were ideological reasons. The first reaction of the Bolsheviks (and other revolutionaries) to the march on January 9, 1905 was quite unambiguous - it almost excluded in their eyes Gapon’s agent role. This is what V.I. Lenin wrote in his article “Revolutionary days“A few days after the massacre: “Gapon’s letters, written by him after the massacre on January 9, that “we do not have a tsar,” his call to fight for freedom, etc., are all facts that speak in favor of his honesty and sincerity, because the tasks of a provocateur could no longer include such powerful agitation for the continuation of the uprising.” When Gapon began preparing an armed uprising abroad, the revolutionaries openly recognized him as their comrade-in-arms. However, the rivalry for influence over the working masses led to the old enmity flaring up with renewed vigor. An additional argument against Gapon during the years of Soviet power was his religiosity - it fit well into the system of evils of the previous regime, described by the ideologists of socialism.

Thus, Georgy Apollonovich Gapon was not a provocateur either in meaning No. 2 or in meaning No. 3. At least there is no convincing evidence of this. As for the first, modern meaning, it has nothing to do with the question we posed - working for the secret police. That's what wrote about the events of Bloody Sunday, Gapon himself: “I really went to the tsar with naive faith for the truth, and the phrase “at the cost of our own lives we guarantee the inviolability of the sovereign’s personality” ... was not an empty phrase. But if for me and for my faithful comrades the person of the sovereign was and is sacred, then the good of the Russian people is most valuable to us. That is why I, already knowing on the eve of the 9th that they would shoot, went in the front ranks, at the head, under the bullets and bayonets of soldiers, in order to testify with my blood to the truth - namely, the urgency of renewing Russia on the basis of truth.” From this we can conclude that Gapon knew that the procession he organized could turn into a bloodbath. But whether to call this a provocation is a matter of assessment.

Did Gapon's political opponents have other documented evidence of his betrayal in favor of the secret police? Perhaps, but they did not reach us. The Socialist Revolutionaries who killed Gapon had enough information about his contacts with security forces. How wrote another leader of the terrorist wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Boris Savinkov, “we... were convinced that evidence of Gapon’s treason would sooner or later be found by itself and that therefore we do not need to reckon with the fact that we cannot present them at the moment.” And this lack of evidence accompanies the figure of one of the most prominent public figures in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century to this day. Except that in school textbooks Georgy Gapon is almost never called a provocateur.

Mostly lies

Read on topic:

1. Z. I. Peregudova. Political investigation in Russia. 1880–1917

2. I. Ksenofontov. Georgy Gapon. Fiction and truth.

3. Six Mysteries of Bloody Sunday 1905

4. A. I. Spiridovich. Notes of a gendarme.

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.