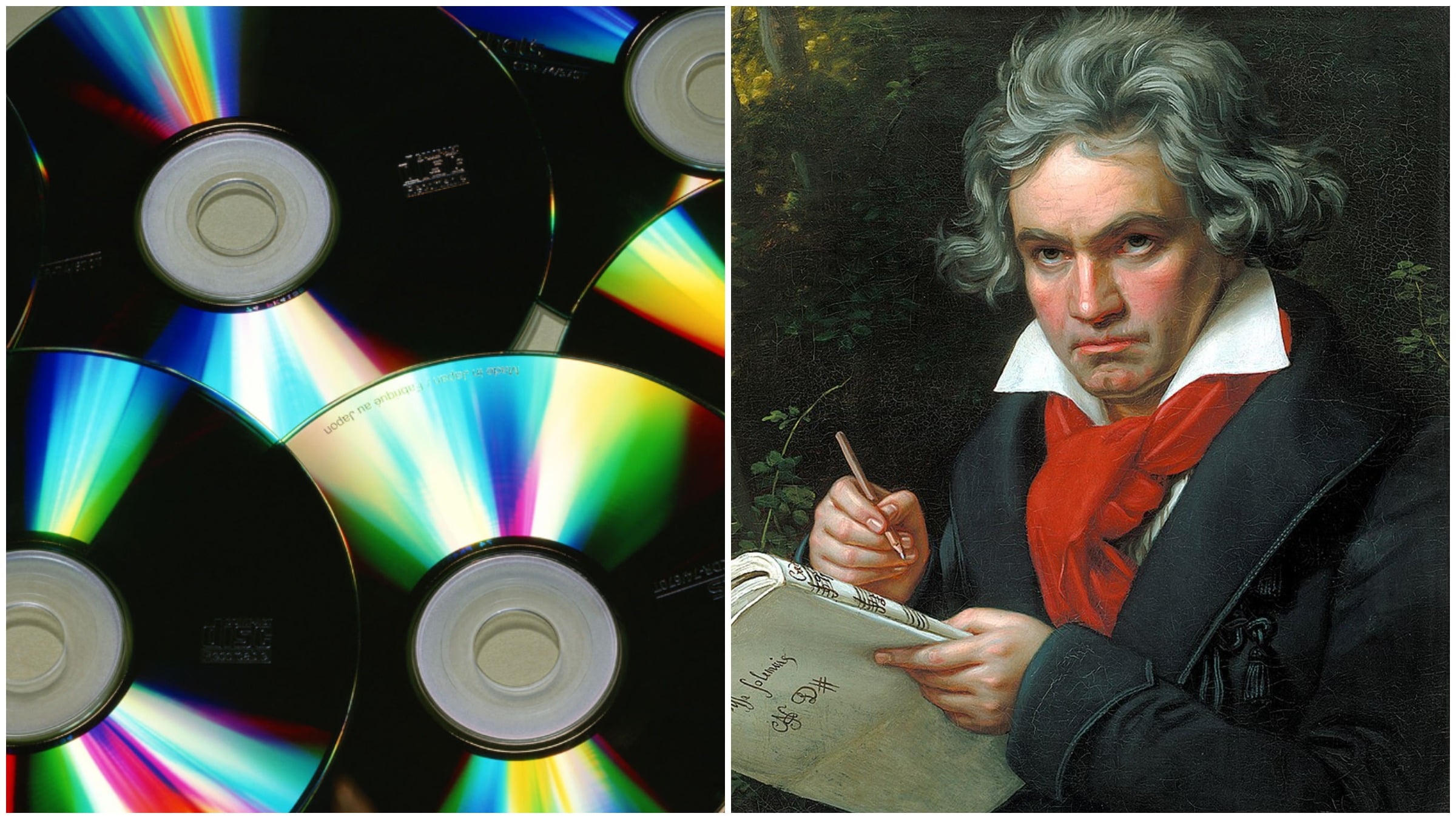

It is widely believed that when choosing the diameter for a compact disc, engineers were guided by the consideration that the entire recording of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, lasting 74 minutes and 33 seconds, must fit on the medium. We checked whether this is actually true.

When Sony President Norio Oga died in 2011, many media outlets emphasized that this was the man thanks to whom the German composer influenced the development of music a century and a half later, because it was Ora who lobbied for the decision on CD sizes. Similar obituaries were published The Guardian, BBC, CBS, The Los Angeles Times, ABC and many others. Ten years earlier, the question of the connection between Beethoven and the diameter of a compact disc sounded on the American TV quiz show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”

In 2018, the authoritative journal Nature published article by Dutch engineer and inventor Kees Immink “How we created the compact disc.” After graduating from the Eindhoven University of Technology, he worked for more than 30 years at Philips, where, in particular, he participated in a joint CD project with Sony. Immink also participated in the development of DVD and Blu-ray formats, wrote more than a hundred scientific papers and received several prestigious academic awards. In 2000, the Queen of the Netherlands awarded Immink a knighthood.

In his article in Nature and Less Known text 2007 Immink talks about the problems that Philips and Sony faced when working together. In 1979 and 1980, the Dutchman took part in a series of expert meetings, which alternated between Tokyo and Eindhoven. At these meetings, representatives of the two companies discussed various parameters of the future CD, including its size. One of the Philips executives, Lou Ottens, proposed a diameter of 115 mm, for which there would be no need to reorganize production lines. In turn, Sony representatives planned to develop the market for portable players and therefore proposed a smaller diameter, only 100 mm. In December 1979, at a regular meeting in Tokyo, it was decided that the diameter of the CD would be 120 mm - this would allow recording an audio track 74 minutes long.

Why did the experts settle on this particular diameter, although initially both Philips and Sony planned to make the disk smaller? According to the "official" versions, which were published According to both companies' websites, Beethoven was very much loved by Sony Vice President Norio Oga and his wife. It was they who insisted that his Ninth Symphony should be completely contained on one medium. Oga told his colleagues that the longest recording known at that time was an orchestra performance under the direction of conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1951, which lasted 74 minutes and 33 seconds. According to another version, the condition put conductor Herbert von Karajan, who was asked to support the invention (although his performance of this symphony played almost 10 minutes faster). In order to fit the entire recording of Furtwängler’s orchestra onto the disc, its diameter had to be increased from 115 to 120 mm.

While Oga may indeed have been a big fan of Beethoven, Immink saw other reasons for lobbying for the 120mm disc. Firstly, Philips could produce CDs with a diameter of 115 mm at much lower costs, because the equipment in factories and the players sold by the company were already configured for this format. Right during the development of the CD, Philips opened a large plant in Hanover set up to produce 115mm media, and Sony did not have such capacity. Secondly, by December 1979, when the final decision on the diameter was made, experts had not yet agreed on the channel encoding method - how exactly the data would be recorded on the medium. Immink developed the EFM code, which made it possible to increase the maximum recording duration by 30% without increasing the diameter of the disk. Surprisingly, his proposal was not accepted, although it would allow the production of 100mm CDs, as Sony originally wanted. It is highly likely that the Beethoven story was an ingenious cover for the Japanese company's real motive - to deprive Philips of a technological and therefore commercial advantage when music began to be released on compact discs.

As Immink writes, he found final confirmation of his guess more than 30 years later. In 2017, in Tokyo, he had lunch with his colleague, Sony engineer Toshitada Doi. When Immink shared with the Japanese his doubts about the “official” version of Beethoven, he replied: “Of course you are right, but it was a beautiful story, wasn’t it?”

Half-truth

- Kees A. Schouhamer Immink. How we made the compact disk

- Kees A. Schouhamer Immink. Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc

- Alexander Rehding. Beethoven's Symphony No. 9

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.