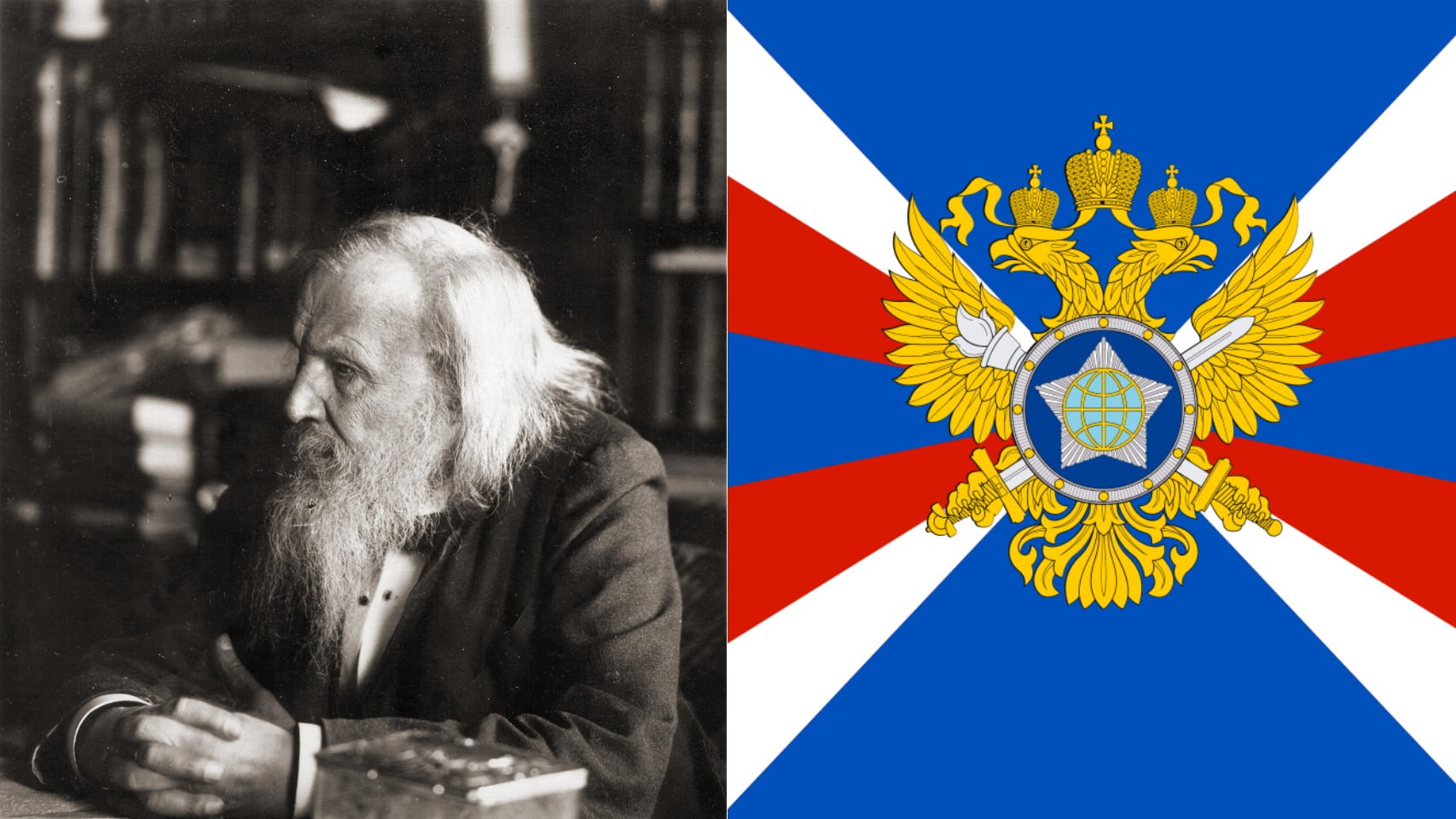

On December 2, 2020, the head of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation, Sergei Naryshkin, named Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev among the most famous people “engaged in intelligence activities, political and military-strategic intelligence.” We checked whether the great scientist had any connection with the secret services.

The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) is considered the successor to the Foreign Department of the All-Russian Emergency Commission and therefore celebrates its centenary in 2020. On the eve of a significant date, the head of the department and part-time chairman Russian Historical Society Sergei Naryshkin gave interview magazine "Historian". Logically, the conversation was dedicated to the past of the Russian secret service. In particular, Naryshkin listed famous people who participated in intelligence activities, including naming the great scientist Dmitry Mendeleev.

Although in the interview the head of the SVR does not specify the sources of his information, they are not difficult to determine. In 1995, the department published “Essays on the history of Russian foreign intelligence” in six volumes. The editor-in-chief of this collective work was Evgeny Primakov, who at that time held the post of director of the SVR.

The first volume, subtitled “From Ancient Times to 1917,” contains a text by Andrei Itskov, “Russia - USA: Attempts at Rapprochement.” In addition to working on “Essays,” Itskov also wrote The book "The Death of Jonestown - a CIA Crime", which "exposes the villainous murder of 918 American citizens in the Guyanese jungle organized by the CIA." It was not possible to find academic publications and articles by this author in reputable scientific journals on history.

Itskov claims that in the mid-1870s, “the flow of cheap American oil, obtained using the latest technologies at that time, literally flooded the world market with this valuable energy product, and Russia began to suffer huge financial losses.” When the idea arose to “deal with American innovations,” they began to look for a suitable “candidate for intelligence officers,” and, according to the author, Mendeleev became him. In 1876, the scientist went to the World's Fair in Philadelphia, where he got acquainted with statistical data, made “many personal contacts” and held many “meetings with prominent American specialists and scientists,” visited oil wells and inspected oil pipelines. Itskov also writes that at the same time, “at the request of the Russian military department,” Mendeleev “tried to find the secret of making smokeless gunpowder,” and “the information received on this issue” made it possible to reproduce the explosive composition and develop a more effective technology. Itskov learned all this from two sources: Mendeleev’s work “On Oil Affairs” and his “papers” from a certain MMA archive (fond 1, file 21, sheet 32). It was not possible to find an archive known by this abbreviation. Apparently it doesn't exist.

In 1996, director of the Mendeleev Museum-Archive of St. Petersburg State University, science historian Igor Dmitriev published analysis of Itskov’s publication. Unlike his colleague who wrote essays for the SVR, Dmitriev is one of the largest specialists on the life and legacy of Mendeleev, who has written more than one study about the scientist. He largely bases his criticisms of Itskov on numerous texts by Mendeleev and documents stored in his museum and the Russian State Navy Archive - unlike MMA, exactly existing.

© John E. Findling

As Dmitriev rightly notes, Itskov himself does not mention any of Mendeleev’s actions that could be characterized as “intelligence.” The chemist had indeed been interested in the topic of oil since the 1860s and participated in discussions about reforms in this area, despite the difference in the importance of oil then and now. incredible. Therefore, the Russian Technical Society petitioned to send Mendeleev to America to get acquainted with overseas experience. Upon his return, the scientist presented a report to the Minister of Finance and published book "The oil industry in the North American state of Pennsylvania and the Caucasus." These texts are not among Itskov’s sources.

In his notes, Mendeleev constantly emphasizes: the Americans told him everything that interested him about their oil production, showed equipment, provided statistics and official reports. In America, Mendeleev did not have to use any “spy” techniques, and there was no need for it: “Our Baku technicians have nothing to learn from the Americans regarding distillation; if you can borrow anything, it’s some mechanical devices, but they are beneficially applicable and will only pay off at such huge factories as the American ones.” There was no secret in the logistical decision to move oil refineries from production sites to sales sites - Mendeleev proposed this idea back in 1863.

The Essays also say that during a trip to America in 1876, Mendeleev managed to figure out a method for making smokeless gunpowder. Itskov, who wrote about this, was not embarrassed that the first samples were of acceptable quality appeared in the USA almost 20 years later - how could Mendeleev spy on them? It is all the more strange to accuse a scientist of stealing or spying on technology if we take into account that, thanks to Mendeleev, smokeless gunpowder appeared in Russia earlier than in the United States. Domestic specialists began development in the mid-1880s, Mendeleev joined the process in 1890, and by 1893 he successfully completed tests. It was possible to obtain high-quality smokeless gunpowder two years earlier than the Americans.

To solve this problem, the scientist again went on a trip abroad to exchange experience, but not to America, but to France and Great Britain. The trip is documented in detail: the chemist kept a notebook and sent letters, and correspondence from the Marine Technical Committee, of which Mendeleev was a member, has also been preserved. According to these data, in Europe the chemist also did not use “spy” methods, limiting himself to official means: for example, thanks to the help of the Russian ambassador, he managed to convince the French minister to give permission to become familiar with the production of gunpowder. Otherwise, the picture was not very different from the events of 14 years ago in America: European colleagues showed Mendeleev’s laboratories and talked about production.

This story has a minimal Bond flair thanks to the son of a chemist, Ivan Dmitrievich. In his memoirs, he retells his father’s memories of that trip: “I was sent abroad by the military department on a secret mission. <…> I also quickly discovered the secret of making French gunpowder, taking advantage of the fact that the gunpowder factory stood on a separate railway line. Taking the annual report of the railway company on the movement of cargo, I found the ratio I needed of the substances included in the production of gunpowder...” It’s funny that this very evidence is not mentioned in Itskov’s essay. However, Dmitriev characterizes the memoirs of Ivan Mendeleev as containing “a lot, to put it mildly, inaccuracies” and draws attention to the fact that in 1890 the scientist’s son was six years old. Dmitriev is sure: if such a story took place, it was designed for children’s perception and did not correspond to reality.

Unlike Newton or Darwin, Mendeleev’s legacy has not yet been presented in the form of a single digital archive, thanks to which all his texts, diaries and correspondence would become accessible to anyone. In such a situation, we are forced to rely on the authority of researchers, the sources they named, and their argumentation. The SVR has not presented any fundamentally new evidence in 25 years. In comparison with a detailed and detailed study by a recognized expert on Mendeleev, a four-page chapter from a book on the history of the SVR with a link to an archive whose existence is in question clearly inspires less credibility.

Fake

- https://historyrussia.org/polemika/intervyu-s-istorikami/est-takaya-professiya.html

- I. Dmitriev. “Special mission” of Mendeleev: Facts and arguments

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.