In various sources you can find a legend that the most famous pizza in the world got its name thanks to Queen Margaret of Savoy, who highly appreciated the recipe. We tried to figure out whether this corresponds to historical facts.

Although the details differ slightly between publications, the general outline of the legend is as follows. In 1889, King Umberto I and his wife Margherita were supposed to arrive in Naples. The royal couple allegedly got tired of fine cuisine, and the organizers of the visit decided to surprise the guests. They asked master Raffaele Esposito to prepare three different pizzas for the queen. At the audience, Margherita preferred pizza with tomatoes, mozzarella and basil, repeating the colors of the Italian tricolor. A member of the royal household even sent Esposito a letter of gratitude, which still adorns the wall of his pizzeria (now called Pizzeria Brandi). In one form or another, the legend is also mentioned in “Wikipedia», and in restaurant promotional materials, and on travel sites, and in cookbooks.

Such stories, widely presented in popular sources, often attract the attention of researchers. In 2014, historian Zachary Novak from Harvard University published article, in which he not only collected already known facts about the appearance of Margherita pizza, but also supplemented them with finds that he made in Italian archives. Novak identifies the main elements of the legend, the consideration of which will help to draw a conclusion about what really happened.

Firstly, archival data casts doubt on the desire attributed to the queen to dilute the boring high French cuisine with simple local food. The banquets hosted by Margarita were considered among the most exquisite in Europe, the best chefs worked at court, and until 1908 the menu was printed exclusively in French.

Secondly, at the end of the 19th century, even by the standards of poor Southern Italy, pizza was considered the food of the poor and was not at all a traditional dish in any Neapolitan family. Moreover, the region constantly suffered from cholera epidemics, which makes the story of tasting dishes of unknown origin even less likely. Finally, why the order was placed specifically with Esposito is also not completely clear, because at that time there were about 60 pizzerias operating in the city and Esposito’s establishment did not stand out from them in any way.

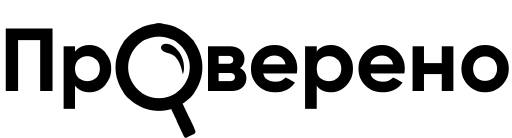

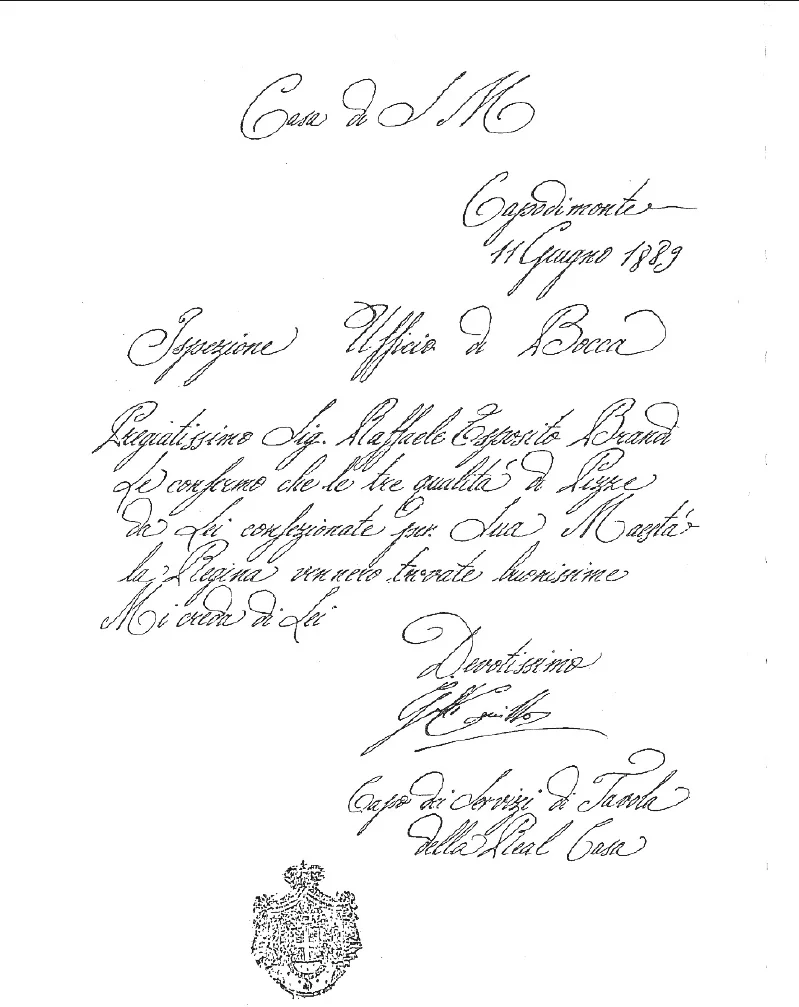

Thirdly, there are great doubts about the authenticity of a letter of gratitude from an employee of the royal court, Camillo Galli, which to this day adorns the wall in the establishment that previously belonged to Esposito. Although such papers were not uncommon in Italy at the end of the 19th century, the researcher was unable to find information about this letter in the archives. The search for traces that Esposito and Galli corresponded at all was also unsuccessful, although all such correspondence was carefully documented. Moreover, the handwriting on the letter does not match the samples of Galli's handwriting, and the seal, which only vaguely resembles the royal one, is located in a different part of the sheet than it was on similar papers. Finally, the letter was written with a ballpoint pen, rather than the then more common fountain pen, on a regular sheet of paper instead of a special form.

Letter of thanks

Raffaele Esposito

Example of a letter written

Camillo Galli

Fourth, the royal couple's visit to Naples in May-June 1889 is well documented. We know all their movements, meetings and events attended, but there is no mention of pizza tasting anywhere. Novak concludes that the beautiful story is nothing more than a myth, but doubts that it was created “from above”: “Given the culinary culture at court, pizza was too simple and far from the queen’s food to create a convincing story for propaganda purposes.”

Where did the legend come from then? The researcher draws attention to the fact that the story of Esposito is not the only one, and stories about how monarchs or aristocrats eat the dish of the Neapolitan poor are part of local folklore. A logical question arises as to why this particular story was replicated. The fact is that in 1932, Esposito's pizzeria was taken over by his nephews, the Brandi brothers. Apparently, in the midst of the Great Depression, they decided to draw attention to their restaurant by creating a family marketing myth. Hence, apparently, the address on the letter of gratitude to “Senor Raffaele Esposito Brandi” - in Italy at the end of the 19th century, men did not sign with double surnames, and Esposito’s correspondence that has reached us confirms this. The legend spread thanks to the pizzeria's flyers, which retold the story of a meeting with the queen, supposedly from a newspaper in 1929 - strangely, the restaurant was called Pizzeria Brandi three years before the brothers began to own it.

So the story of the queen admiring the food of the Italian poor turned out to be, in fact, the story of a clever marketing move that allowed a Neapolitan pizzeria to survive difficult times.

Legend

Read on topic:

- Zachary Nowak, Folklore, Fakelore, History: The Origins of the Pizza Margherita

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fakelore

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.