According to popular belief, the artist and inventor allegedly held a party in which a boy completely covered in gold paint took part. Because of this, his thermoregulation was impaired and the child died. We have verified the accuracy of this story.

In the domestic tradition, there are two main versions of this story, in which the place and time of action, the main participants and other details differ. The first is presented in the multi-volume Children's Encyclopedia, which was published at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s under the editorship of Dmitry Blagoy and Vera Varsonofyeva. In the volume "Man" (1960) said: “In the last days of 1496, in the luxurious castle of the Duke of Milan, Moro, they were preparing for the New Year holiday. <…> The organization of the holiday was led by the great artist and unsurpassed mechanic Leonardo da Vinci. He planned to glorify the golden age of the world, which came after many years of the Iron Age of devastating wars. To depict the Iron Age, blacksmiths under the supervision of Leonardo da Vinci made a huge figure of a reclining knight, clad in armor. And the golden age was supposed to be depicted by a naked boy, covered from head to toe in gold paint. It was the son of a poor baker. His father provided him for the pleasure of the Duke for money. At the height of the festive fun, a defeated knight was brought into the hall. From his womb came a “golden boy” with wings and a laurel branch in his hand. He looked at those around him in fear, pronouncing a memorized greeting to the Duke.” The boy subsequently died. In the version outlined at about the same time by Alexei Dorokhov in the edifying book “This is worth remembering: a book about how to behave so that both you and others can live better and more pleasantly” the events moved from Milan in 1496 to Florence in 1515, the customer of the holiday instead of Duke Moro (aka Lodovico Sforza) was Lorenzo Medici, the occasion was the glorification of Pope Leo X instead of the New Year, and the performer was Raphael instead of Leonardo. Moreover, Dorokhov names the boy's name - Paolo, his father turns from a baker into a stonemason, the boy's sister named Annunziata is added to the characters, and the narrative is replete with fictional details. The story about the “golden boy” is still quite actively republished on social networks, for example in Facebook, "Odnoklassniki" And "Yandex.Zene".

Even a cursory comparison of two Soviet sources is enough to raise doubts about the veracity of the story. The number of differences in texts that appeared in the same country at approximately the same time seems unrealistically large. Even greater questions arise after studying the biography of the authors of these statements. Thus, the article of the “Children’s Encyclopedia” is placed in the volume “Man”, which in general dedicated anatomy and psychology, and the story about the “golden boy” serves a kind of lead-in to the story about thermoregulation. The author of the article we are interested in was Alexander Kabanov - physiologist and the author of a popular anatomy textbook, but not an art critic or historian. It was not possible to find confirmation that Alexei Dorokhov, the author of the second version of the story about the “golden boy,” had such an education.

At the same time, earlier texts with a similar plot are also known. So, in 1900, Dmitry Merezhkovsky published the historical novel “The Resurrected Gods, or Leonardo da Vinci.” The version presented by the writer is largely matches as outlined in the “Children's Encyclopedia”: the action takes place at the festival of the Duke of Milan, and Leonardo is the initiator. At the same time, Merezhkovsky clarifies the boy's name - Lippi, but does not specify that what was happening was part of the New Year's holiday (which in Italy at that time was generally didn't mention). Although the writer graduated Faculty of History and Philology of St. Petersburg University probably had much more expertise in this topic than the physiologist Kabanov; we should not forget that his text is still a work of art.

However, Dorokhov’s version also finds earlier “confirmation”. In 1924 there was published the story “The Golden Boy”, in which we are talking about the beginning of the 16th century, Raphael, the Medici and Florence. The author of the text is Margarita Yamshchikova, who wrote under the pseudonym Al. Altaev. In this "story from the history of Italy" the boy is also named Paolo, and the narrative is artistic rather than academic. Yamshchikova does not provide any references to sources, and it was not possible to find confirmation that the writer had a historical or art history education, as well as experience in working with historical documents.

In English-language sources, the story of Leonardo and the “golden boy” is also found in texts that cannot be considered historical or art historical. For example, the American poet George Sylvester Viereck wrote in 1912 poem "The Ballad of the Golden Boy", based on this plot. In the note the poet calls this story about Leonardo is an “anecdote” that, by his own admission, he discovered in an unnamed “hygiene book.” In 1935, the author of an article in the New York newspaper The Brooklyn Daily Eagle used a more categorical description of “myth” (by the way, in his presentation the boy survived thanks to the help of Leonardo). Similar text at the same time came out in several other regional American newspapers.

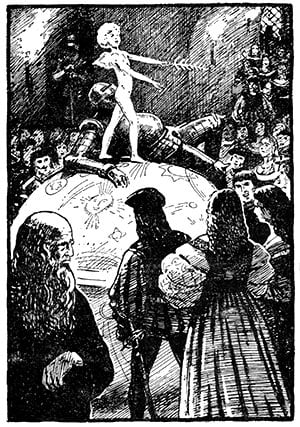

If we turn to authoritative historical and art history texts, we can find that a similar episode actually took place in Italy during the Renaissance, but its descriptions are seriously different from those set out in Soviet books for children. Giorgio Vasari, the first to compile biographies of artists of that era, reports, that in 1513, before Lent, in Florence they staged a triumph similar to the ancient Roman one in honor of the election of Leo X as Pope. Lorenzo Medici, who saw the triumph, decided to organize an even more magnificent triumph, for the design of which he invited, in particular, the painter Jacobo Pontormo. The celebration included “a chariot, or rather, a triumph of the golden age, furnished with the most magnificent and richest ingenuity, an abundance of relief figures made by Baccio Bandinelli, and the most beautiful paintings painted by the hand of Pontormo. Among the relief figures, the figures of the four cardinal virtues deserve special praise. In the middle of the chariot stood a huge sphere that looked like a globe, on which a man in completely rusty armor lay prone, as if dead. His back was open and cut, and a completely naked and gilded boy crawled out of the wound, representing the resurrecting golden age and the end of the iron age, from which it arose and was reborn thanks to the election of a new high priest. <…> I will not keep silent about the fact that the gilded youth, who served as an apprentice to a baker and endured this torment in order to earn ten crowns, died very soon after that.”

As can be seen from this passage, Vasari does not mention either Raphael or Leonardo in connection with the story of the “golden boy”. Perhaps the latter became a protagonist in some accounts of this story due to the fact that the founder of modern art criticism notes: Piero da Vinci worked on the first of the triumphs he described. The art critic calls him Father Leonardo, although this denies author of comments to the original text. In general, quite little is known about da Vinci’s family, but the artist himself was already over 60 in 1513, so his father’s active participation in the celebration is extremely unlikely. Moreover, according to some sources, Da Vinci Sr. died back in 1504.

Considering that Vasari was a pioneer of art criticism, inaccuracies in his work are understandably found by later colleagues. At the same time, the episode with the “golden boy” avoided such criticism, and more modern researchers also do not mention either Leonardo or Raphael in connection with this story. For example, the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, in his work on Italy during the Renaissance, although leads Vasari's story tells about another "golden boy". 40 years before the events in Florence, a relative of Pope Sixtus IV and the future cardinal Rafael Riario gave a magnificent reception in Rome. In one of the halls, as Burckhardt claims, “a living child, gilded from head to toe,” played the role of a kind of fountain - he took water into his mouth and, spinning, released it in a stream. The story of a Swiss historian confirm and archival letters researched in 1996 by American Meg Licht. Neither these historians and art critics, nor other authoritative sources could find any mention of Leonardo or Raphael in connection with this plot (the latter had not yet been born at all).

Thus, two episodes are known with the participation of the “golden boys” in different celebrations in Italy during the Renaissance. The first of them, confirmed by the memoirs of contemporaries, occurred in 1473 in Rome, a child inside the room depicted a fountain statue, and his death (as well as his participation in organizing Leonardo’s reception) was not reported. The second took place in 1513 in Florence - during a solemn procession through the city, the “golden boy”, symbolizing the golden age, crawled out of a statue of a knight in armor and subsequently died. As Vasari presented it, the author of this idea was not Leonardo or Raphael, but Jacobo Pantormo. We were unable to find a refutation of this attribution in more modern studies.

For clarity, you can summarize the versions described above in the table:

| Kabanov and others. | Dorokhov and others. | Vasari et al. | Burckhardt etc. | |

| City | Milan | Florence | Florence | Rome |

| Year | 1496 | 1515 | 1513 | 1473 |

| Place | Lock | Open space | Open space | Palace Hall |

| Occasion | New Year | Celebration in honor of the Pope | Celebration in honor of the Pope | Reception |

| Customer | Lodovico Sforza | Lorenzo Medici | Lorenzo Medici | Rafael Riario |

| Executor | Leonardo | Raphael | Jacobo Pantormo | Not known exactly |

| Boy's role | Depicts the "Golden Age", emerging from a statue of a knight in armor, which symbolized the Iron Age | Depicts the "Golden Age", emerging from a statue of a knight in armor, which symbolized the Iron Age | Depicts the "Golden Age", emerging from a statue of a knight in armor, which symbolized the Iron Age | “Plays” the role of a fountain |

| Consequences | The boy spent several hours in the cold hall, then Leonardo found him, but he was unable to save the child and he died | The day after the procession, the boy died at home from pneumonia | The boy “died very soon”; no other details were provided. | Unknown, but no death reported |

As can be seen from this table, the versions presented in Soviet children's literature (and before that in some literary texts like Merezhkovsky's novel) are seriously different from those given by Vasari and Burckhardt and are not confirmed by modern experts. Although in the West already in the first half of the 20th century the story of Leonardo and the “golden boy” was characterized at best as an “anecdote” and at worst as a “myth,” Soviet authors wrote popular texts based on it, without being professional historians or art critics. And if in the presentation of Altaev and Dorokhov the plot was fictionalized relatively harmlessly (they attributed the idea to Raphael, slightly changed the dating, came up with names for the boy and his relatives, etc.), then the writer Merezhkovsky, and after him later the physiologist Kabanov, changed the story almost beyond recognition.

Mostly not true

- Is it true that if you completely cover a person's skin with paint, they will die?

- G. Vasari. Lives of famous painters, sculptors and architects

- J. Burckhardt. The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

- M. Licht. Elysium: A Prelude to Renaissance Theater

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.