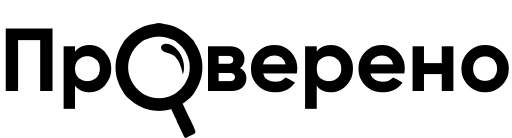

In April 1983, the major German magazine Stern issued a press release with shocking news: the publication had several dozen volumes with previously unknownmi diary entries of the Fuhrer. Was it really possible that for almost 40 years after the war no one could find such valuable documents?

62 notebooks with notes from Adolf Hitler gradually arrived at the Stern editorial office over the course of two years. The employee who negotiated with the owner of the diaries claimed: they were found at the site where a plane with part of the Fuhrer’s personal archive crashed in 1945, and now a resident of the GDR is ready to smuggle them over. The publication of such valuable materials was supposed to become a sensation, and foreign publications were invited to join the process: the English The Sunday Times and the American Newsweek.

The fact that there were some previously unknown diaries of Hitler in Stuttgart became known in the late 1970s. Rumors circulating among West German collectors reached Gerd Heidemann, a staff photographer. Sternfascinated by the Nazi legacy. Having learned about the diaries, Heidemann began to insist: they should be published as soon as possible. To do this, the photographer found the contacts of the owner of the diaries, who introduced himself as Peter Fisher.

The first telephone conversation between them took place in early 1981. Fischer assured Heidemann that he owned 27 diaries of the Fuhrer and numerous other relics from the time of the Third Reich. He also demanded that experts and historians not be involved in the verification, and that secrecy be maintained when discussing the publication with the magazine. Heidemann agreed to pay for the originals with management Gruner+Jahr - publishing house that published Stern. Each volume of diaries was valued at several tens of thousands of marks, and Heidemann took part of this amount for himself. By 1983, it turned out that Fischer had a total of 62 volumes of diaries and their value was gradually increasing.

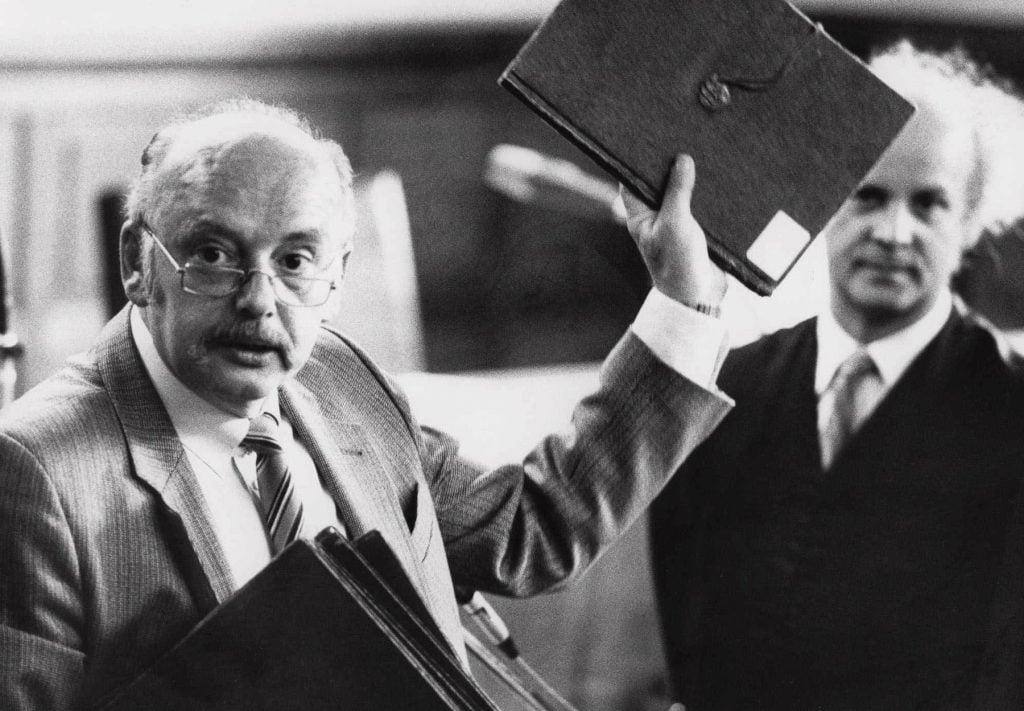

To give the publication weight, at least some kind of expertise was necessary. Heidemann, who represented Stern, agreed to check with representatives of the German Federal Archives. They were asked to compare a page from the diaries with samples of Hitler's handwriting - the experts came to the conclusion that the diary was genuine. The British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who was initially skeptical, was also involved in the verification. Representatives Stern convinced him that a chemical examination confirmed that the diaries were written during the Third Reich. Moreover, Trevor-Roper was given thousands of pages to look at - it was impossible to believe that someone was making fakes in such a volume.

April 22, 1983 Stern issued a press release about the upcoming publication, and three days later a press conference dedicated to the diaries was to take place. During this period, numerous doubts about their authenticity began to be voiced, expressed by journalists, scientists, and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Trevor-Roper also doubted his initial verdict. The magazine was threatened with a lawsuit for disseminating Nazi propaganda, and one of the publication’s lawyers transferred not a page, but three full volumes to the archive.

Specialists from the Federal Archives came to the conclusion that the diaries were written on modern paper, and the bindings were made of polyester, which became available to the mass consumer only in 1953. Graphologists noticed that Hitler's signature does not correspond to the known originals. To reach the final verdict, another 15 volumes were distributed between the Federal Archives and specialists in St. Gallen, Switzerland. On May 6, 1983, experts confirmed: the diaries were written over the past two years, the handwriting only resembles Hitler’s writing style, and the diaries themselves are compiled from speeches, comments and already known texts of the Fuhrer.

A few days later, on the border of Germany and Austria, Konrad Kuyau surrendered to the police - it was he who, under the false name Peter Fischer, discussed the publication of diaries with the photographer Stern. During a search, Kuyau was found to have empty notebooks similar to those containing Hitler’s “records.” On May 26, 1983, the forger confessed; he and Heidemann were tried for theft from Stern 9.3 million marks (about $3.7 million) as fees for the sale of fake diaries. In 1985, both were sentenced to four years and eight months in prison. Two years later, Kuyau was released early due to health problems. Until his death in 2000, he owned a gallery in Stuttgart, where he exhibited and sold fakes of great painters. The canvases were proudly signed with the name Kuyau.

© The New York Times

How did this become possible? It turned out that Kuyau, a native of East Germany, was a professional forger. He forged literally everything: from his own documents to lunch coupons. One day Kuyau noticed that wartime artifacts were very popular in Germany, and began creating and selling fakes. Among them were paintings allegedly painted by Hitler and even the allegedly lost third volume Mein Kampf. Photographer Heidemann, in turn, was fascinated by the Nazi legacy, was constantly in debt and wanted a luxurious life. Considering that the process of transferring the diaries went through him, Heidemann could falsify the results of the examinations: for example, during a preliminary check in the archive, experts compared a page from the “diary” not with a real sample of Hitler’s handwriting, but with a fake by Kuyau.

The scandal with Hitler's fake diaries is considered one of the largest in the history of European journalism. Two editors Stern were fired, and the magazine lost its reputation as one of the flagships of quality journalism for a long time. Brian MacArthur, who participated in the preparation of the publication, explained: “The publication of Hitler's diaries was so tempting that we all wanted to believe that they were genuine. Moreover, we had to continue to believe in their authenticity until proven otherwise. <…> We were about to release the most amazing sensation of our career.” In 2013, most of the diaries were transferred to the German Federal Archives, where they are stored and today in the fund dedicated to the history of the media.

Fake

- R.Harris. Selling Hitler: The Story of the Hitler Diaries

- C. Hamilton. The Hitler Diaries: Fakes that Fooled the World

- https://echo.msk.ru/programs/netak/2635501-echo/

If you find a spelling or grammatical error, please let us know by highlighting the error text and clicking Ctrl+Enter.